Clem Labine

It Looks Weird – but Vitruvius Would Approve

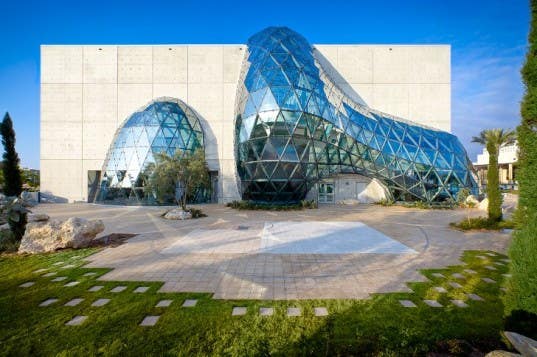

I am a harsh critic of irrational contemporary architecture. That’s why I was amazed when I found myself rather liking the new Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, FL. At first glance, it appears it might be just another self-indulgent piece of polymorphic "starchitecture". But the closer I looked, the more I realized the building, designed by HOK’s Florida office, is not as strange as it first appears: Despite its raffish façade, it is a rational structure.

For starters, the building opened on time and was $700,000 under budget – quite unusual for a large, complicated (68,000-sq.-ft., $30-million) project. And the museum’s lead architect, HOK’s Yann Weymouth, used existing technology – rather than calling for invention of untried building details. Admittedly, the museum’s bulging glass atrium, called “The Enigma,” challenged the capabilities of engineers at Novum Structures. But the glass bump that provides the museum’s distinctive look was built using glass enclosure technology that Novum has proven elsewhere. To test my belief that this museum is a rational structure, I measured it against the Vitruvian triad of "Firmitas, Utilitas, Venustas" – and the building comes out quite well.

The Vitruvian Triad

FIRMITAS: As for durability, the building’s primary design imperative was an ability to resist 165-mph hurricane winds. To this end, Weymouth designed a simple three-story box made of 18-in.-thick reinforced concrete. Assuming there will be occasional flooding, all of the museum’s art and HVAC systems are placed on the second and third floors – well above all historic flood levels.

One obvious question: Is the glass Enigma water tight? All panes of the glass atrium are flat and triangular, held in a matrix of metal tubes. – similar to a geodesic dome. It’s been in place over six months – and so far no leaks. Unlike the 18-in. reinforced concrete, the laminated glass is only certified for a Category 3 hurricane (130-mph winds), but all the art is separated from the exterior glass atrium and other openings in the outer concrete walls by an interior concrete wall and metal roll-down shutters.

UTILITAS: The building certainly is functionally suitable for displaying the largest collection of Salvador Dali paintings in the New World. Because the Enigma (named after a Dali painting) starts as a skylight at the top of the building, the galleries are well lit. And anyone familiar with Dali’s surrealist paintings will recognize the appropriateness of the organic way the Enigma appears to have started like a giant water drop that rolled off the top of the buildings and became frozen as it hit the ground.

VENUSTAS: To relieve the monotony of the museum’s durable, economical concrete box, architect Weymouth split the monolithic concrete with the amorphously shaped glass skylight/atrium. If you like Dali’s melting watches in his painting “The Persistence of Memory,” you’ll see the appropriateness and beauty of the Enigma. Weymouth’s architectural inspiration is fabulously eccentric, giving the building humor and character reminiscent of Dali himself.

Architect Yann Weymouth has come up with a non-traditional museum building that is both rational and functional – and which will please the vast majority of its visitors. Congratulations!

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.