David Brussat

Architecture for Beginners

Adam, Flaubert, Bouvard and Pécuchet

Robert Adam’s essay “Reproduction and Invention,” concluding the latest edition of Traditional Building, distills the differences between the two phenomena so intrinsic to architecture. Notwithstanding the difficulty of plucking out just one passage to exemplify its qualities, here is the third paragraph:

And yet, to produce something today that looks just like something from the past is to produce something that isn’t the same, but is different. The first time round it will have been an invention and an invention is not the same as a reproduction. It may look the same but people don’t feel the same about an invention as they do about a reproduction and what matters is what people feel about things. That is why we make architecture.

Adam’s essay transforms complexity into simplicity, which reminds me of Gustave Flaubert’s novel Bouvard and Pécuchet. In the 1881 story, two Parisian friends use an inheritance to finance a move to the country. There they try to farm by reading book after book about agriculture and its many fields, but end up failing at each one in turn, tripping over the difference between knowing and doing. Despite this, they look down their noses at and make enemies of their neighbors, scorning the traditions that frame the ways of the village.

The mistake made by the two friends is to transform simplicity into complexity. Flaubert’s purpose in writing Bouvard and Pécuchet was to explore the relationship between knowledge and folly. Readers will immediately assume that I would like to turn this into a fling against modern architecture. How right they are!

As Adam points out, an intimate relationship exists between invention and reproduction. Along with all the other things modern architecture has abandoned in its headlong rejection of the past is the understanding of this relationship. Instead of treating invention and reproduction as two sides of the same coin, modernism treats them as opposites: invention is good; reproduction is bad.

This, of course, is ridiculous.

Eventually, tired of agriculture, Bouvard and Pécuchet delve into other fields, eventually that of architecture. Here is a passage in which some might find mental habits imbedded deeply in the profession today:

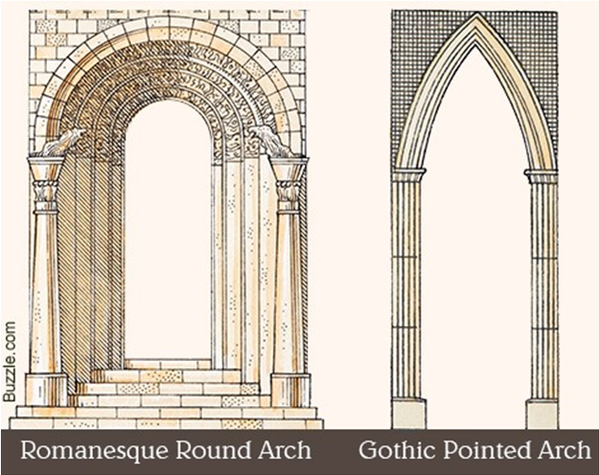

Soon they were able to distinguish the different periods, and scorning the sacristans they would say, “Ah! A romanesque apse! That is twelfth century! There we are back in the flamboyant!”

They tried to understand the symbols carved on the stone capitals, like the two griffons of Marigny, pecking at a tree in blossom; Pécuchet saw satire in the choirmen with grotesque jaws who terminate the strapwork at Feugerolles; and as for the exuberantly obscene man covering one of the mullions of Hérouville, according to Bouvard, that proved that our ancestors were fond of bawdy jokes.

They ended up finding the least mark of decadence quite intolerable. Everything was decadent, and they deplored vandalism and fulminated against whitewash.

But a monument’s style does not always agree with its presumed date. In the thirteenth century the semi-circular arch is still dominant in Provence. The ogive may well be very ancient! And some authors challenge the priority of Romanesque over Gothic. This lack of certainty upset them.

Let’s see. Bouvard and Pécuchet treat architecture with a curatorial rather than a holistic attitude. They overinterpret the meaning of buildings. They assume the basest of human instincts. They take matters to extremes. They vacillate between different experts. They only believe what everyone else believes. Do they sound like anyone you know who is an architect?

Flaubert died before completing the final chapters of the book, but he had for years compiled a “Dictionary of Received Ideas,” which is attached as an appendix in most editions. In it he spoofed the conventional wisdom of his day. Here are his entries for Architects and Architecture:

Architects: All idiots; they always forget to put staircases in houses.

Architecture: There are only four types of architecture. Leaving aside, of course, the Egyptian, Cyclopean, Assyrian, Indian, Chinese, Gothic, Romanesque, etc.

Today, the equivalent entries might read:

Architects: All idiots; they always hide the front doors of buildings.

Architecture: There is only one type of architecture. Leaving aside the modernist, there is every other type, which each reflect their own era, which is not our era and so is irrelevant.

Robert Adam addresses this folly near the end of his TB essay, referring to the tradition by which the history of architecture moves forward:

The ancient classical Orders—Doric, Ionic, Corinthian—go back more than 2,000 years; the arch and the dome 2,000 years; the glazed arcade and taller buildings 150 years. There’s no reason why this should stop. It just has to be a recognizable part of the tradition. It’s like writing a novel: each time you write a new chapter, it won’t be the same as the last chapter but it won’t make any sense unless it carries on the story from the previous chapters.

As Adam says, there’s no reason why this should stop. But it was stopped anyway, and Flaubert, were he alive today, could write volumes about the bumbling Bouvards and Pécuchets of modern architecture.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.