Carroll William Westfall

History’s Damage

Today’s history of architecture is a propaganda vehicle for Modernism. It educates architects and the public about this most conspicuous and useful of the arts, and unfortunately, it casts tradition as inimical to progress.

This history tells about buildings from the earliest beginnings to the present day, always as the product of influences in the irresistible march of progress with a few creative geniuses leading architecture into the future. In this march new traditional styles replace their predecessors with the culmination of stylistic progress in the Modern Age’s Modernist styles.

But note: This is a history of buildings, not of architecture. These buildings satisfy the three Vitruvian conditions of commodity, firmness, and delight that today might be put as function, economical construction according to code, and favorable press reviews.

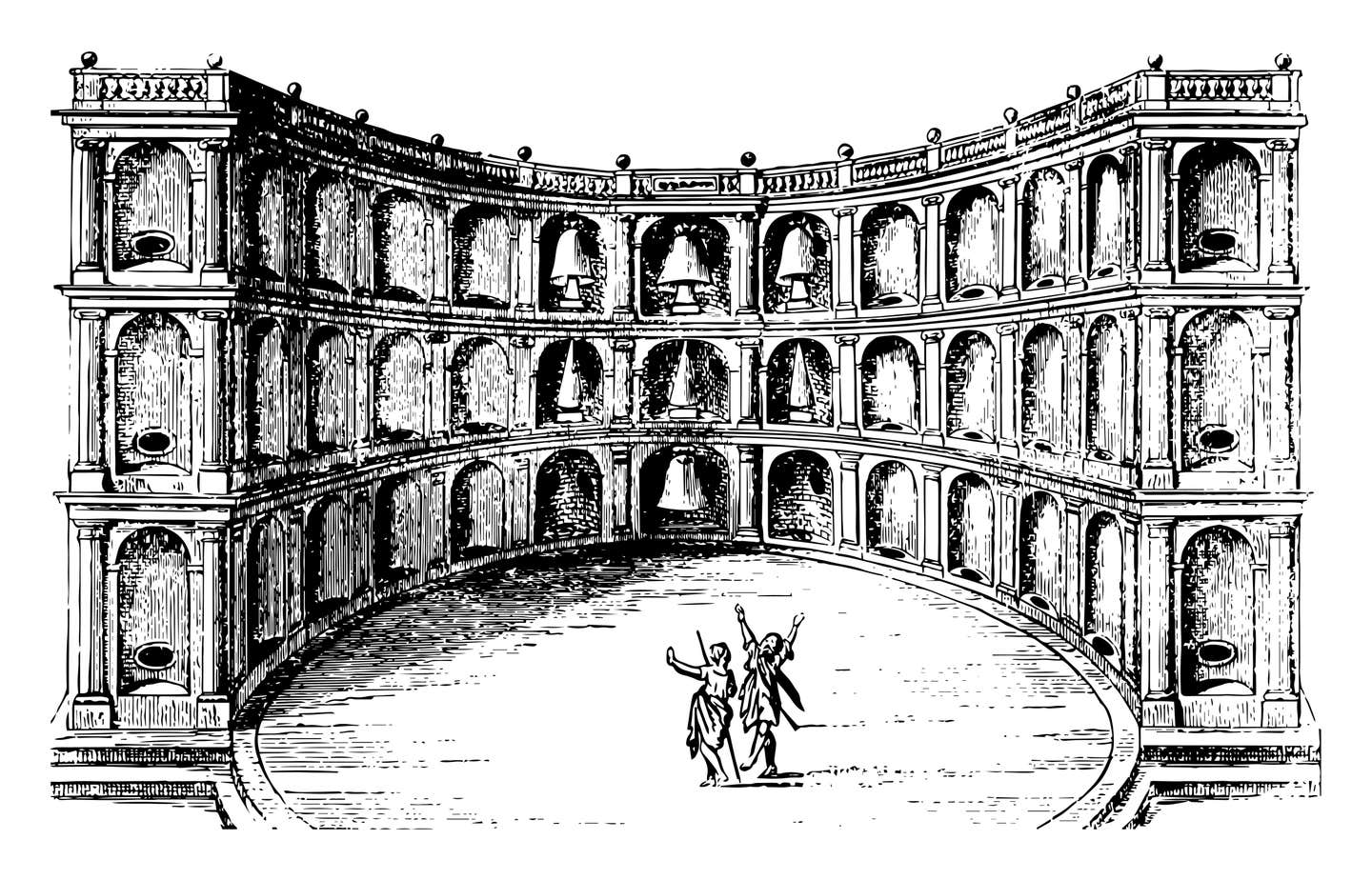

But that trilogy is secondary to what Vitruvius and his successors down to the threshold of the modern era sought. Necessary for the art of building, the art of architecture required more. Architecture imposed three more, tougher criteria, but these are now ignored. Two criteria offer the beautiful by connecting the building to the order, harmony, and proportionality of cosmic Nature. They are symmetria, which means proportionality and not merely bilateral axial equality, and eurythmia, which calls for the architect’s adjustments that make the beauty perceptible. Both imitate or draw from Nature’s beauty that is discernable in geometry’s circle and square, in the well-formed human figure, and in the relationships between various numbers. His third criterion is decor; it requires that the building fulfill its purpose as a beautiful servant to the common good. That same word, decor, refers to the obligations Roman citizens must fulfill in their personal lives and in their civil and religious affairs. These obligations, like buildings, are ranked according to the relative dignity of the purposes with the temple the most important, then the theater, basilica, residence of the superior classes, and on down to lesser buildings that Vitruvius largely ignores. Note that Vitruvius’ discussion of the beautiful occurs in Book III, devoted to temples.

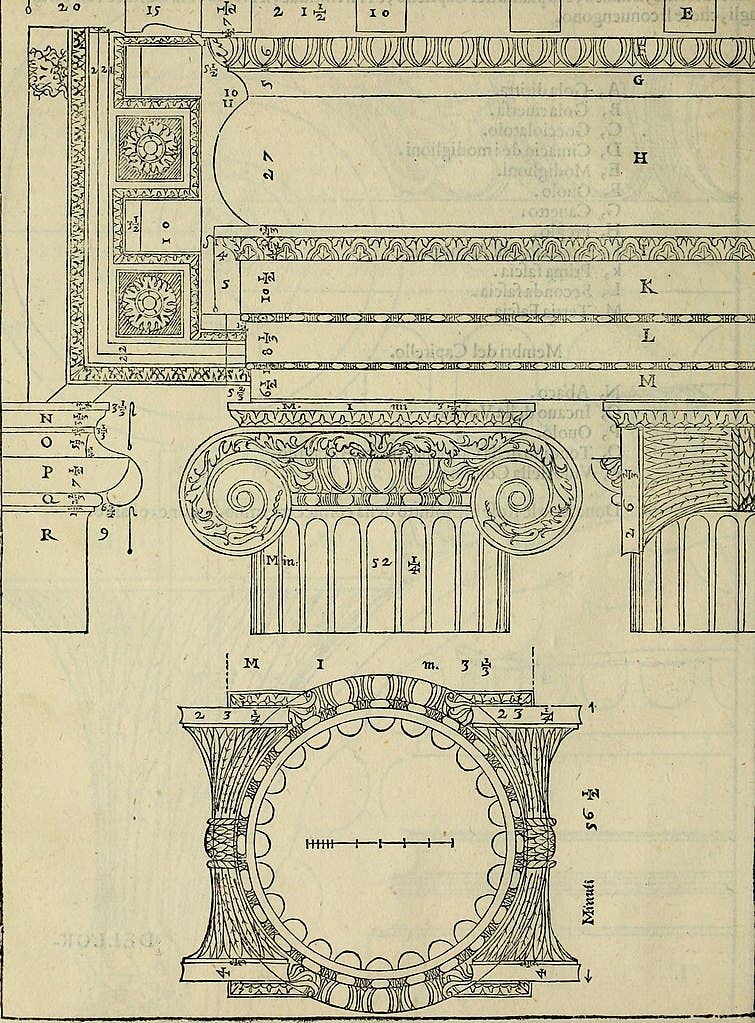

Vitruvius’s treatise was revised and enlarged in the middle of the 15th c. by Leon Battista Alberti who also transposed the pagan cosmos into one God had created. In Books (i.e., chapters) I-VI he covers the art of building. The ranking of buildings by the purpose they serve comes in Books VII-IX. And achieving the beautiful in architecture comes in Book IX. Note that he identifies the columnar orders as a building’s most beautiful ornament and discusses them when he discusses churches. Note also that beauty is essential for architecture, arguing forcefully that its presence is not based on mere opinion but comes from embodying the reasoned order in God-created Nature.

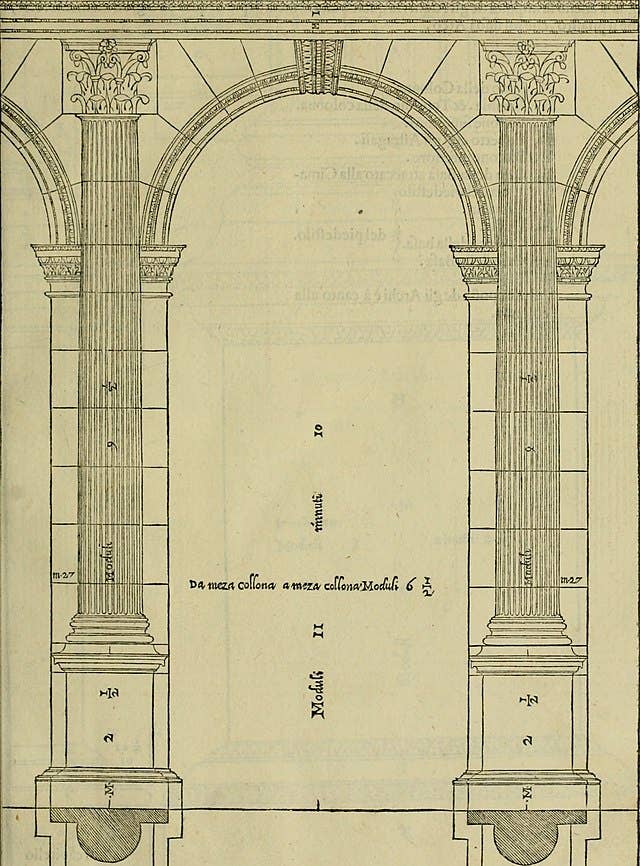

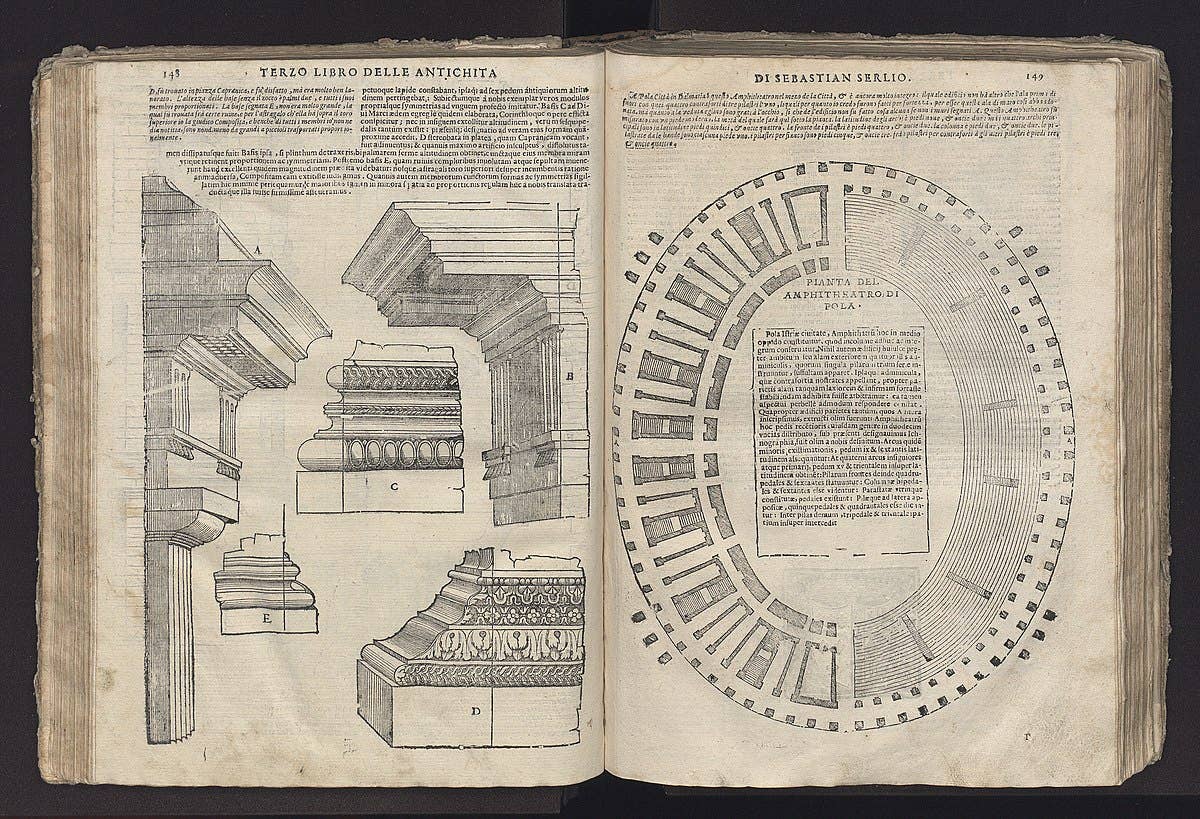

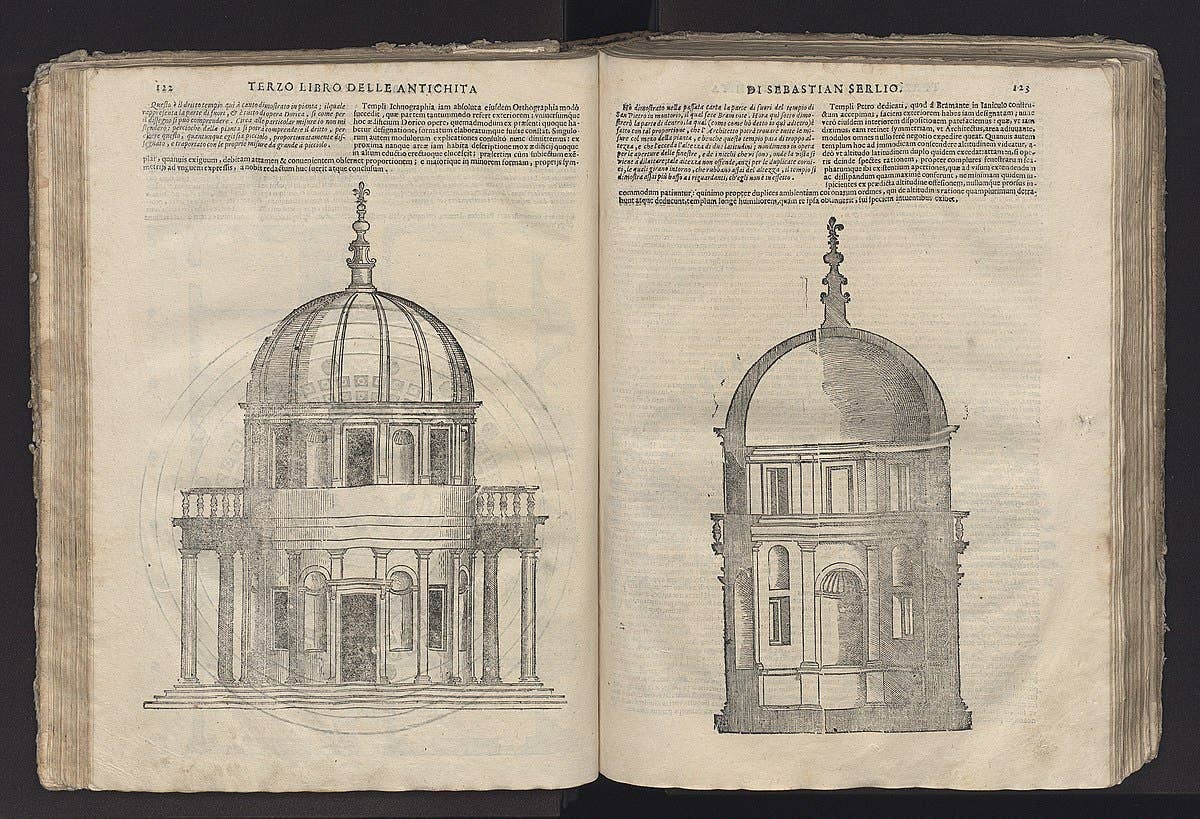

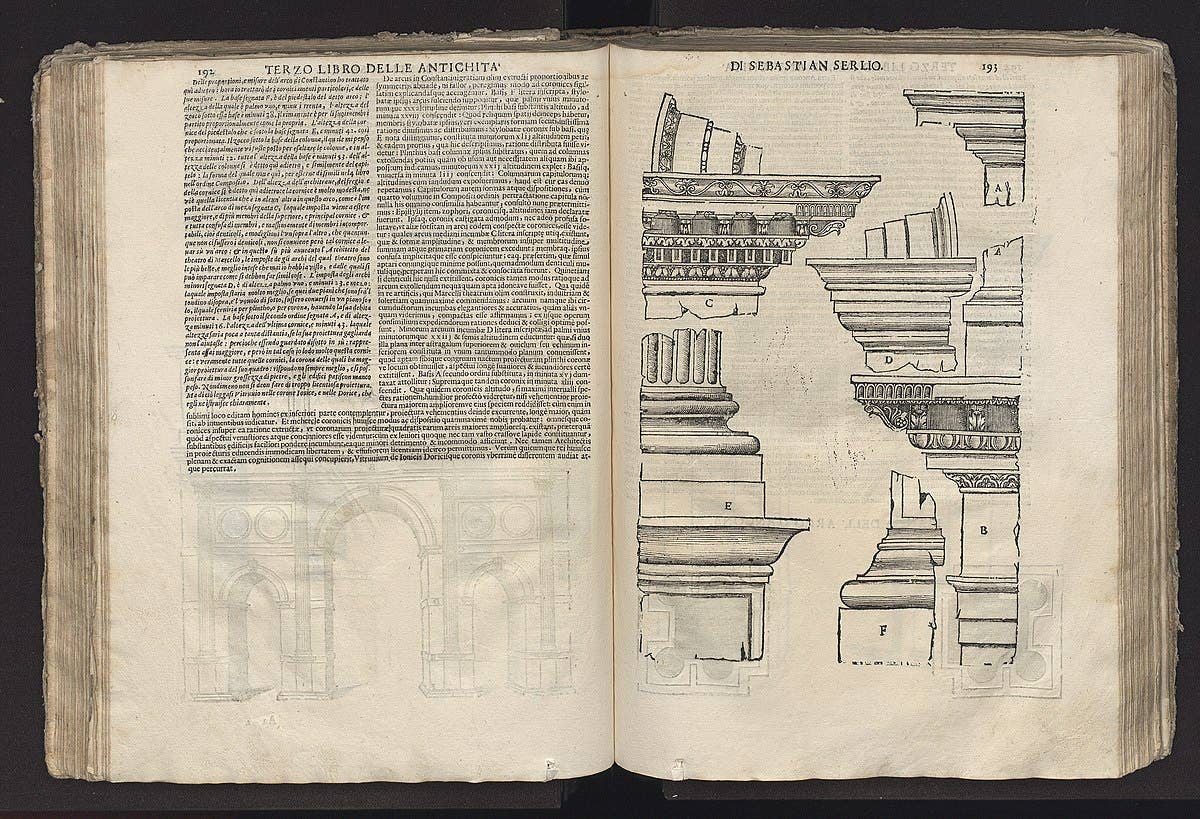

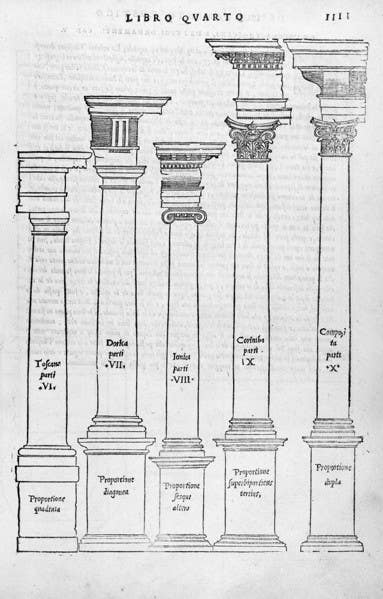

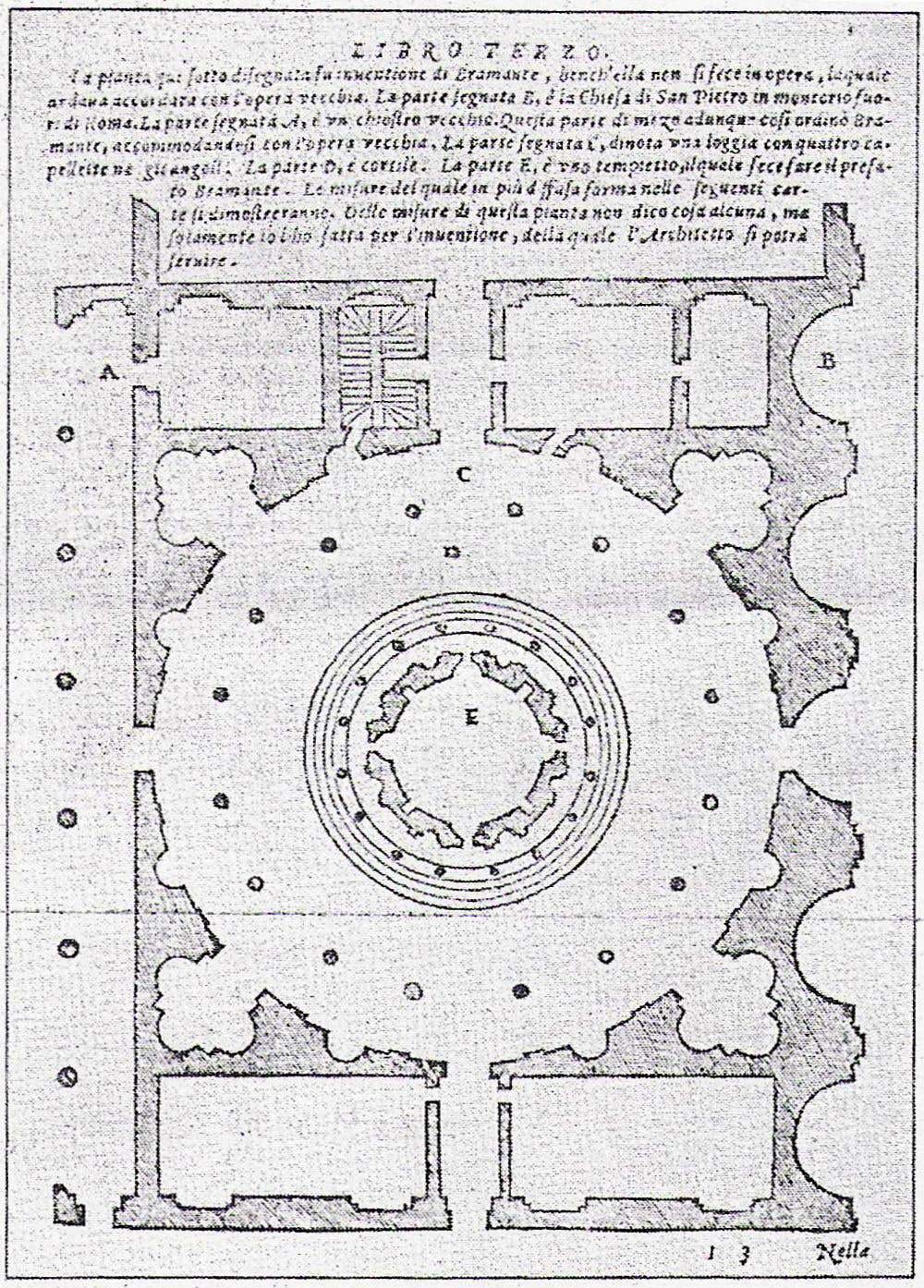

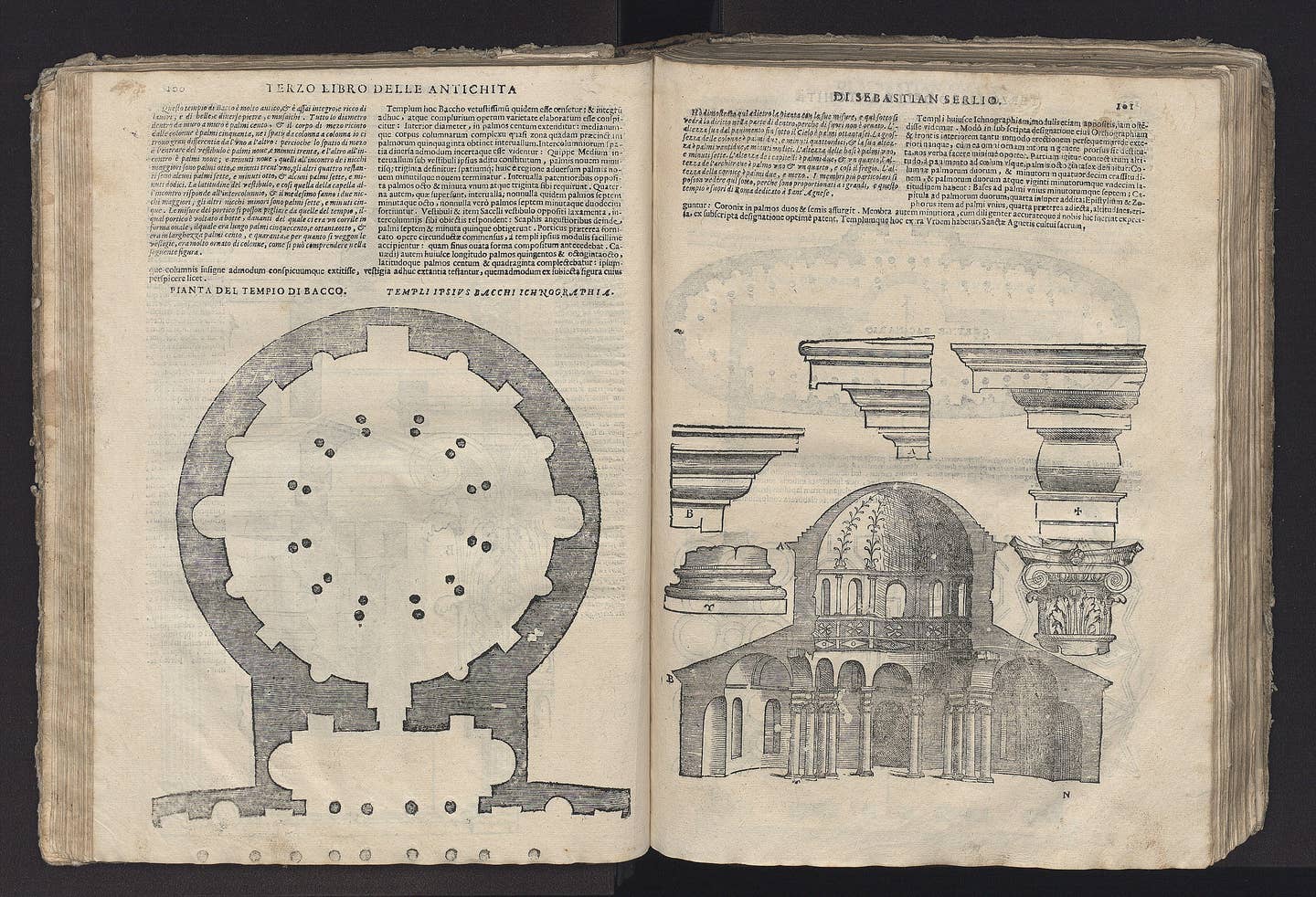

The columnar orders identify a building as classical. Vitruvius and Alberti described the orders, but the first image combining all five, each the same but each different and different in the same way (Joseph Rykwert), was in Sebastiano Serlio’s treatise from 1537. Serlio also published a wide range of ancient buildings and a few modern ones, as did several others, most beautifully and influentially Andrea Palladio in 1570. His brief text gives a precis of Alberti’s, arguing that architecture imitates Nature, and his images offer a wide range of ancient buildings and his own designs. From the 16th c. on, books on the orders have been legion.

The instruction provided by treatises gradually declined as architects’ lives became more important.. During Palladio’s lifetime Giorgio Vasari published The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Two centuries later the interest shifted to histories and instruction shifted to buildings. Then in the next century the historical narrative assumed command. It incorporated the Zeitgeist’s influence in producing the buildings of each successive age with the idea of progress propelling the present into a beneficent future.

These new factors in history writing—style, era, examples, influence, Zeitgeist—reveal the effects of developments in the natural sciences that were challenging and disproving ancient theories and interpretations. Perhaps events were unique to their era and offered no useful instruction for the future. Perhaps human nature was not unchanging as the ancients thought but was malleable and changing. Some French academicians argued that their modern buildings were superior to ancient predecessors, which led to rejecting the objective status of the beautiful obtained by imitating Nature’s order, harmony, and proportionality. Instead, beauty was a transient resident in the eye of each beholder, its presence felt by the viewer and immune to reasonable disputation.

And architecture was leagued with painting and sculpture, a creative visual art, a fine art or beaux art, offering pleasure to sight. Architects had traditionally been trained through apprenticeship except for a few in academies established to assure that their patrons were well served. Learning involved studying exemplary models. During the 19thcentury national academies were reconstituted and enlarged, first in Revolutionary France, to provide Europeans with buildings that portrayed the nation’s place within the classical tradition. A few Americans studied at the French Academy of the Beaux Arts, and when American universities began offering instruction in architecture, that was the program introduced, first at MIT in 1868 and then at Columbia in 1881.

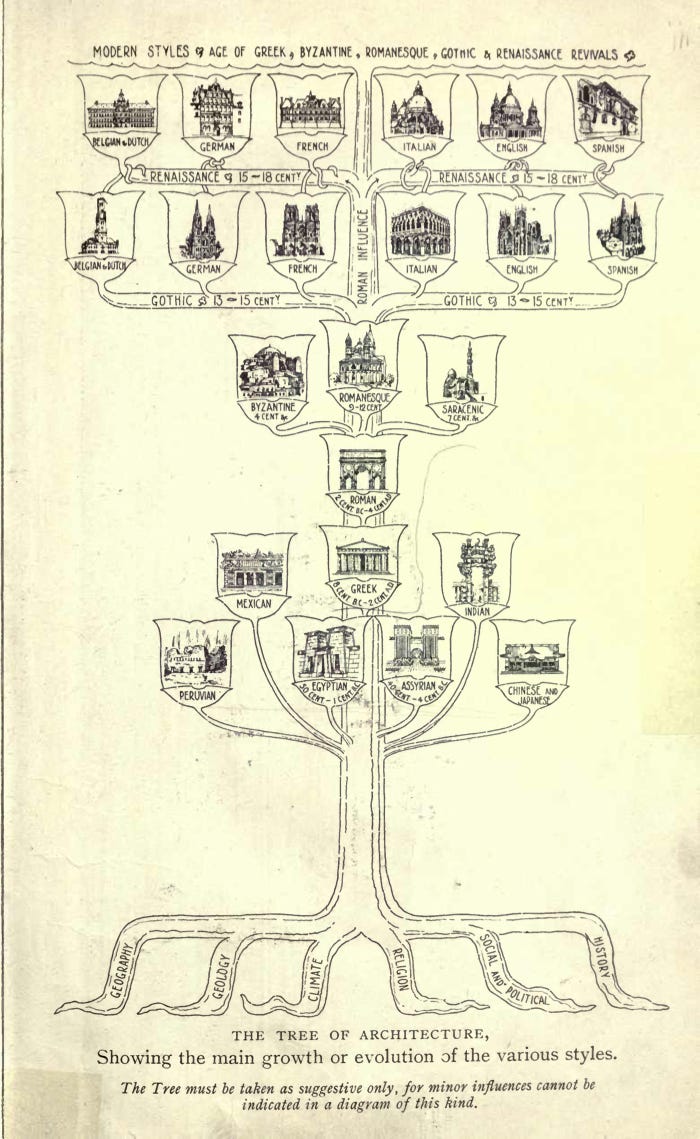

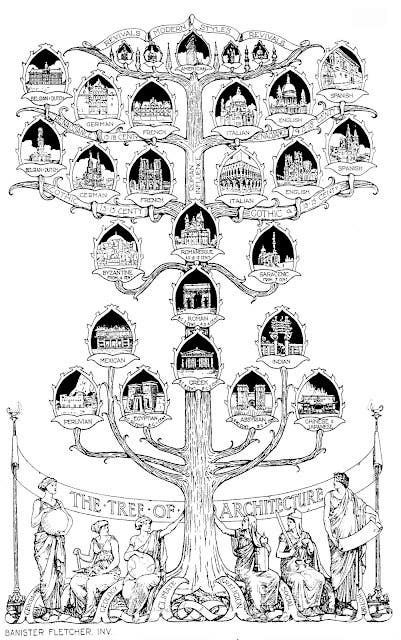

The histories educating architects and public alike presented buildings in sequences of varying traditional styles. A memorable image shows the Tree of Architecture whose branches carry the fruits of the eras nourished by the influences identified as GEOGRAHY, GEOLOGY, CLIMATE, RELIGION, SOCIAL, HISTORY. It first appeared in the 1901 edition of Sir Banister Fletcher’s 1896 A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method. A revision after 1902 put Danial H. Burnham’s Flatiron Building in New York City as architecture’s crowning achievement among “REVIVALS MODERN STYLES MODERN STYLES REVIVALS.”

Also in 1896 A History of Architecture by Columbia’s A. D. F. Hamlin began instructing the architects who would absorb Modernism. In the 1928 edition we learn that in the 15th c. the Renaissance turn from the Gothic “laid the foundations of modern civilization.” Here was a “protest of the individual reason against the trammels of external arbitrary authority.” The movement survived the 19th c., “an age of extraordinary progress along mechanical, scientific, and commercial lines.” The “artistic spirit has never been wholly crushed,… it has repeatedly been directed in wrong channels, with ‘Modern architecture’ oscillating “between the extremes of archaeological servitude and an unreasoning eclecticism.”

After Hamlin’s 1926 death his son wrote the final chapter covering contemporary architecture. He opens shouting “INDUSTRIALISM. … [It offers] steel skeleton construction, and the wide use of reinforced concrete.… [and] the growth of new types—office building, loft building, factory.” Furthermore, “contemporary architecture tends to become international.” And soon “THE GROWTH OF MODERNISM. New forms in art followed naturally the feeling

. . . that the old had passed away, that a new world was ahead.” Many designers found it “illogical to dress the [new] materials in the forms of the past.”

Gropius and Mies van der Rohe brought their Bauhaus system to Depression-era America in 1937 to challenge architectural traditions. In the booming post-World War II era, a new historical narrative was launched, and soon affected everyone involved in the construction of important buildings—the CEOs of major corporations, government officials, directors and philanthropists in cultural institutions, and so on. Andres Duany has pointed out that when these enthusiastic sponsors of Modernism used their own money to buy a new suburban house, they preferred anything traditional to anything Modernist.

The canonic narrative was now based on Nikolaus Pevsner’s An Outline of European Architecture from 1943, a full-throated advocate for Modernism.

New styles appeared “because a new spirit required them.” Architecture, Pevsner intones, “applies only to buildings designed with a view to aesthetic appeal. … the history of European architecture … [is] a history of expression, and primarily of spatial expression.” No architecture; just buildings. Nothing here about beauty or service to the common good.

Modernism fulfills history’s destiny. “Modern architecture,” Marvin Trachtenberg tells us in Architecture (2nd ed., 2002), “is many-sided and ever-changing because modern life is many-sided and ever-changing.” Nearly a hundred pages later, in reaching the 1970s, “Architects no longer needed to labor under a genealogical burden of having to be the true and loyal sons and daughters of the great modern masters, …. Architects are empowered by a new freedom of architectural choice and invention.” And so the many styles of Modernism tumble out one after another.

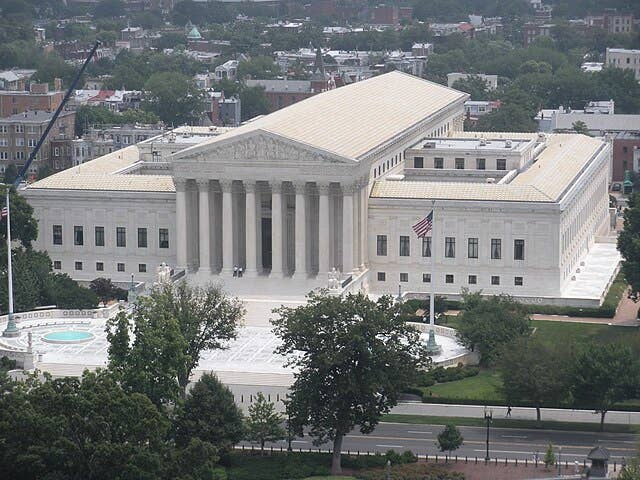

Modernist buildings no longer seek to become architecture. They satisfy functions and offer to some people the pleasure of seeing them, but they are merely stylistic, creative art objects. Their builders forget that all buildings are public things, and they no longer try to offer beauty as a counterpart to the common good, something that only traditional architecture can do and always has done.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.