Carroll William Westfall

The Good and the True in Urbanism

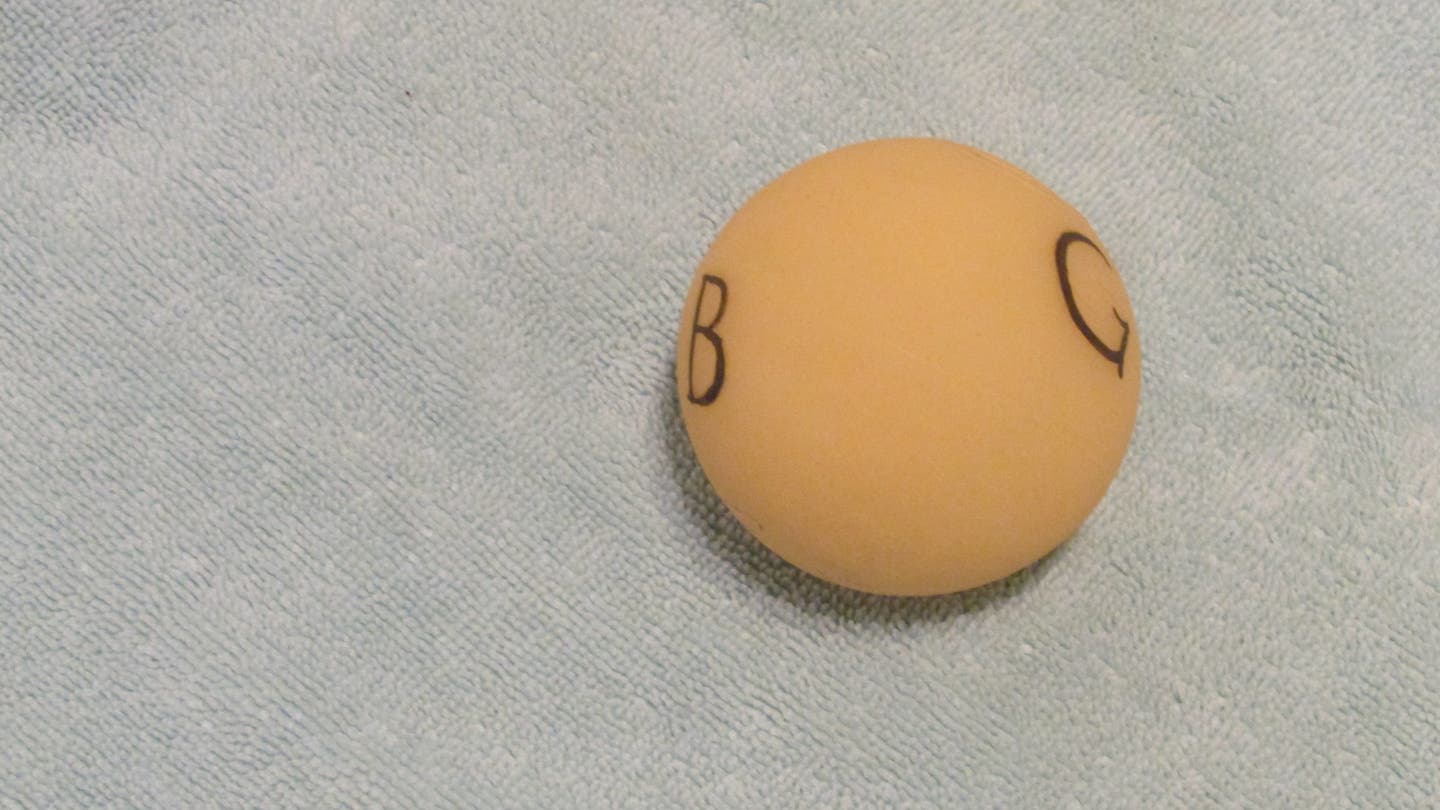

Urbanism makes the place where we protect and enjoy our natural right to pursue our happiness, which resides in our enjoyment of the good, the true and the beautiful. In my previous opinion piece, I noted that these three aspects of happiness share their ideals in the inner core that has been given many names--God, the gods, Nature, or whatever name we prefer for the moral center of a cosmic universe that we share with our individual, human nature. In that core are the ideals for the justice and the good in our actions, the true for what we know, and the beautiful for what we make. I also noted earlier that we can think of these three qualities of happiness like three parts of a ball’s faces that never overlap but share a common core.

We often confuse these three qualities with one another. An example is the Hitler problem: Hitler was evil; he built classical buildings; therefor classical architecture is now a forbidden style. (Fig. 1)

Yes, Hitler was evil, but the evil his buildings served does not condemn the classical now. The classical, like every tradition, serves and expresses authority. Hitler used authority to serve evil, but it is also the architecture that serves our authoritative institutions. (Figs. 2, 3, 4) Would a glass box, a rehabbed warehouse, or a doublewide express the authority of the institutions at work in the Supreme Court, the Capitol and the White House?

We know that the beautiful and the good are not interchangeable values, if only unconsciously, because we do not cringe in encountering the Pantheon in Rome, built by an emperor responsible for reprehensible actions in the name of the gods it honored. Similarly, non-Roman Catholics find pleasure in visiting the Vatican, and Americans in Paris do not shield their eyes from monuments built by royal tyranny.

We often invoke the good in our speech, which reminds us of the central position that morality occupies. For example, we say, “It is good to know that,” a statement about the pleasure in knowing something but not necessarily a judgment that it is true. Similarly, we say of a building, “That’s a good design,” but that does not necessarily mean it is a beautiful building; it might just be the least expensive or most functional design.

It is part of human nature to pursue the happiness found in justice and the good. In earlier eras one person or small group held the power to dictate to others what constituted good and bad acts and extended that to what to believe and used beautiful things such as buildings to express and explain the basis for that power. Our constitutional regime is very different. We hold it as a self-evident truth that all people are equally endowed by nature to define and pursue happiness as he or she understands it. A corollary is that now just as always, each individual is born into a natural family whose duty is to equip the person to become an adult participating with others in communities, large and small.

Communities operate with laws to guide good behavior and inhibit lawlessness. The law’s roles, as John Locke put it in 1690, is “not so much the limitation as the direction of a free and intelligent agent to his proper interest.” (2 Tr., §57). Locke’s insights persuaded us to take control of the laws away from one person or a small group and write them for ourselves because using reasoned discourse people of good will with the necessary “skill and learning to determine” and “sense to discern” when guided by conscience can determine what does and does not serve the common and the individual good. As a result, “We the People” make the laws for civil orders from the nation down through its subsidiary parts of states, counties, cities and even economic improvement agencies.

Now to urbanism. The civil order builds (or allows to be built) buildings to serve and express their role in serving the civil and religious institutions that will facilitate the common pursuit of happiness. Each building expresses the authority the institution has relative to others in the urban or rural ensemble it joins. But buildings are not necessarily wed to the institutions they were built to serve and express. When the institution changes the building may remain; in the 7 century, the Pantheon became a Christian church; now it is better known for reverence to beauty than to Mary or the gods.

The shift of authority from the few to “We the people” produced a vast transformation of laws concerning justice. Conspicuous examples are doctrines of equality and the outlawing of slavery that derived from changed understandings of the enduring and universal ideals of the good in the moral core of the cosmos. Another changed the role of facts relative to the true. The facts uncovered by empiricism began to let the art of building put the art of architecture into retirement and with it the truth that a building could convey.

Vitruvius’ familiar trilogy of commodity, firmness and delight refers to the conditions that the art of building must satisfy. Those conditions can be judged on the basis of facts and empirical standards. Commodity becomes function, which seeks efficiency in, for example, a volume adequate for a particular task or a calculation of cost per square foot. Similarly, firmness came under the control of factual data about strength of materials, costs of labor and materials, and structural calculations. And so too delight, which offers pleasure and will be a topic for the next opinion piece.

In the art of building without aspirations for the beautiful that architecture seeks the facts are allowed to speak for themselves. (Fig. 5). Lacking is the fiction that tells the truth. Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, and so on use facts, often untrue, but they enhance the audience’s pleasure and, more importantly, draw people behind the narrative where they can discern truth about human nature and behavior.

And so does traditional architecture, whether medieval or classical. We are held in rapture when we see skinny piers that can’t possibly be stout enough to reach that high and hold those vaults. In the classical we take pleasure in columns much larger than necessary to carry that pediment. (Figs. 6, 7) Facts are needed for stability, but the facts of a raw steel structure, brut concrete, or an engineer’s drawings and numbers do not elevate a building to architecture.

To express the narrative of nature’s forces in the building’s materials and to express the role and authority of the building’s service to the common good require fiction. Certainly, Cass Gilbert’s Supreme Court Building’s function must serve janitors, interns, litigants, judges and spectators, but in addition it must give a convincing expression of the authoritative role of this supreme tribunal of the nation’s law.

Traditional architecture, and especially classical architecture, provides an apparatus of forms that allows fiction to convey convincing truths about stability and provide a common or familiar body of forms to allow comparisons of relative levels of authority and variety of purposes that make an urban realm.

Instead, we often hear the slogan that “Truth to materials!” is required to honor authenticity: the material doing the job must be exposed or at least expressed. Would those sloganeers allow paint over wood on an early New England temple front, or strip the marble off the Pantheon to expose its brick interior, or expose the brick cores of the orders, for example at the University of Virginia?

The ideology demanding authenticity treats a building not as facilitator of the individual or the common good but as a product “of its time.” Forbidden is using a style of another time in our time, which has its own style. Times change and so must styles, this ideology declares, and so must architecture.

But styles belong to products of the art of building, not to the art of architecture. If the building seeks only to satisfy that lesser art it will not achieve architecture; if it seeks to satisfy the beauty of the higher art of architecture, it will use the art of building necessary to do so.

Some in our age, and most architects now, may believe that their job is to satisfy structural and functional efficiency with an authentic style or even to find their pleasure in extravagant, individual creative expressions with disregard, or misguided regard, for the building’s role in serving and expressing its role of the institutions that are necessary to protect and facilitate the pursuit of happiness.

They miss the point that pleasure properly offered is a portal to the happiness pursued through service to the common good of the good in how we act, the true in what we know, and the beautiful in what we make and build.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.