Carroll William Westfall

Face to Face with Traditional Buildings

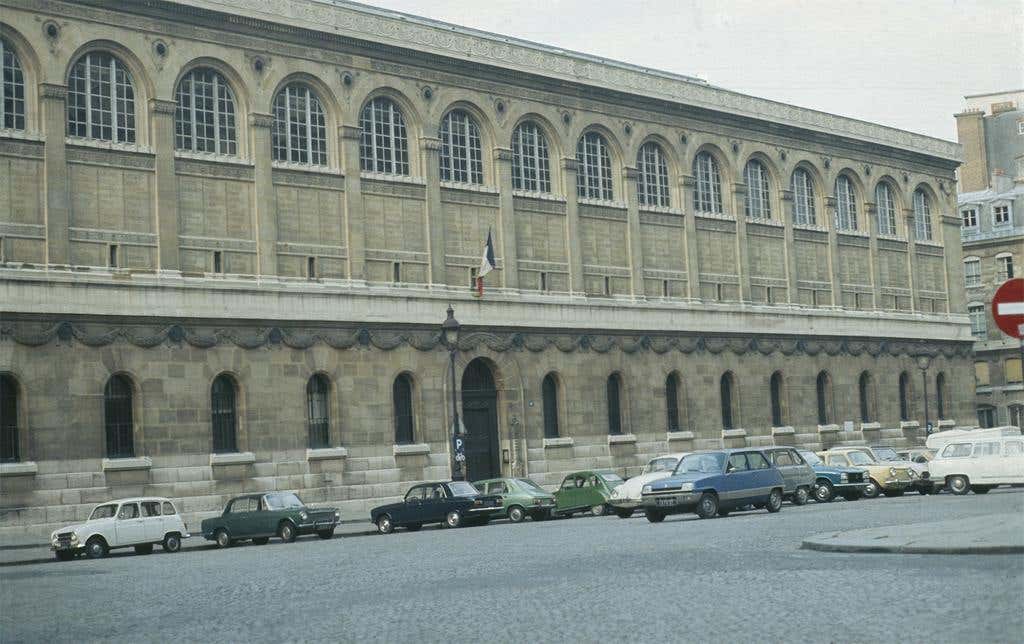

The façade is the most important part of a traditional building. It is the face it presents to the public. While its massing plants it in its place, its composition and facades reveal its character and express its role among other buildings in serving the common good, which every building is obliged to do. (figs. 1-2)

The word façade comes from face, which is certainly a person’s most important public body part. Whether a mug shot or a driver’s license image, it identifies a person. A face can suggest a person’s mood, hint at what she has in mind, unintentionally reveal what he is really thinking, and display a reaction to what she encounters in the world. Important meetings are held face-to-face while a blank public often expresses detachment and anonymity. Unwittingly the face may reveal secret thoughts, and it might not be able to hide lies.

These are uniquely human qualities of human faces, and we can do these things because our face has the body’s most small motor muscles. Is it happenstance that it sits closest to the brain and farther from, but not disconnected from, the heart?

When we want to know a person’s character we scrutinize the face to read conduct and character. We judge character to anticipate what she might do, hoping for a congruence between the expressive character, or what we see, and the generative character, or what is done.

People take care of the face they present to the public. An excess of charm might reveal a dissembling person or one with a poor record of following through. Women primp and groom to enhance their appearance, and men scrub and shave (or not) and put their hair in place. An excess in either gender can be taken to be a mask hiding the true character. Levy Leiter, the man in charge of credit for his partner of Marshall Field in Chicago, who had H.H. Richardson design his Wholesale Store, refused credit to a man who dyed his mustache: If he will lie about that, he is not to be trusted to repay.

The face we see is an outer shell; we read the smiles, frowns and other expressive displays without looking below the surface at the muscles and other interior equipment that produces them. In like manner, we accept the building’s façade to display its character without probing unless we believe that dyed mustaches are enough to reveal character.

The building’s expressive character tells us the most important thing about it, which is the role it plays among other buildings in making the city. Like the face, this is much more important than the workings of the structure and other technical issues going on below the surface. Its generative character, that is, the point of departure for its design that will allow it to express the particular purpose it will serve, comes from the formal character of buildings serving that same or similar roles, a comment that takes us to the two roles a building’s façade plays.

One is to have the façade connect it with the formal tradition of the buildings it will join. Traditional architecture makes traditional urbanism, and traditional urbanism is built one building at a time with each new one intended as a complement and good neighbor to its predecessors. Like a good citizen it does not use its place in urbanism as a stage to show-off but as a contributor to the common good.

The other role is to express the purpose it serves in promoting the common good. Here again like a good citizen it brings its unique qualities to serve a common, public good that is composed of the several enduring purposes of any community that facilitates the pursuit of happiness for all of its members.

The elements of that common good, elements that a good city makes accessible to all the people, are union, justice, tranquility, the common defense, the general welfare, and the blessings of liberty sought through the political life conducted under the framework of our Constitution. The urbanism we build facilitates that pursuit, and urbanism’s beauty evinces our commitment to that purpose. Like any good citizen, its individual presence must display a character that benefits the whole.

It bears repeating that the public face is more important than the tectonics at work behind what we see or the particular functions that serve the purpose it expresses. It has always been so: recall that ancient Greek temples were riotously colored, that beneath the Pantheon’s marble interior is lowly brick, and that the beauty we enjoy in seeing the stone and terra cotta faces of modern traditional buildings are held in place by hidden steel frames.

Traditional architects know that expressing purpose is more important than serving functions: it is more important that form follows the purpose the building plays in the urban realm than having the form follow its immediate function in serving that purpose. Purposes serve the broad, human needs of a people and a society. These include worshiping, celebrating, passing judgment to assure justice, educating (figures 3-7), assembling with others (figs. 8-10), protecting and nurturing the family, making available the goods that sustain life and offer pleasure, and so on.

These encompass our enduring needs and aspirations. Every society has formulated its own way for the character of buildings to serve and express these purposes and to provide the innovations in response to change over time, but that expressive character expresses purposes that are shared by all people always and thereby also expresses a basic and universal humanity.

The varying traditions of architecture reveal that we are all part of the same human family with the same needs and aspirations. Many different and often changing functions serve those purposes, but in past, present, and future they have been and can be accommodated within buildings that express both enduring purposes and their own unique character.

The façade is the face that reveals a building’s commitment to enduring human purposes. Tradition bequeaths the apt qualities, and innovation fits them to the building’s time and place.

Tradition here is a guide and not a straitjacket. Familiarity identifies a building’s purpose; its unique rendering makes it at home. This interplay between tradition and innovation is vital in keeping urbanism alive and attractive. Buildings, like friends and family members, age but retain their character while offspring become trusted chips off the old block, and the face of one generation can be recognized in its successors.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.