David Brussat

Explosive Preservationists in Manhattan Debate Townhouse

In the morning of July 10, 2006, Dr. Nicholas Bartha, 66, took his own life by blowing up the townhouse he had resolved to live in until his death. The story of marital failure leading to lawsuits leading to the gas explosion is too sad to recount and beside the point of this post. The lot at 34 East 62nd St., on one of Manhattan’s wealthiest blocks, has been empty for a decade. The battle to build anew has pitted preservationists against each other, and exposes the preservation ethos at its worst.

The New York Times and The Architect’s Newspaper reported on the battle over the most recent design proposal.

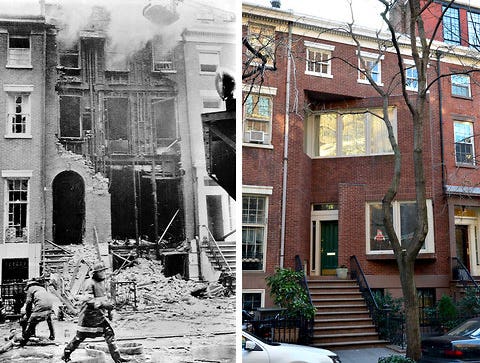

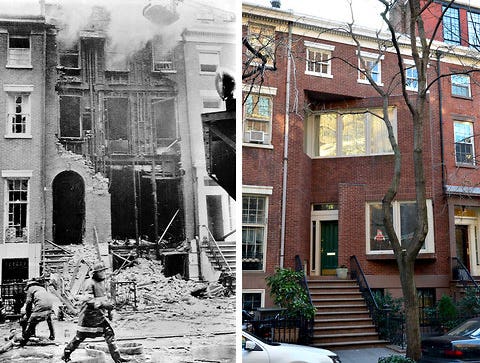

The controversy reminds me of the 1845 Greek Revival townhouse in Greenwich Village that was demolished during a 1970 attempt by the Weather Underground to build a bomb. It was replaced in 1978 by a quasi-modernist townhouse of brick, designed by Hugh Hardy in the same style except that its three bays seem to swivel on a vertical access so that half of it swings in on the building facade and the other half swings out. Really quite an interesting response to the site’s history, much more ingeniously creative than might be expected of a modernist. Lovely, in fact.

The first idea to build on the site of the exploded Upper East Side townhouse was more predictably modernist – determined not to fit into its context. Designed by Preston Phillips, it was nonetheless okay’d by the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, but in the aftermath of the 2008 recession it was not built.

That the commission seemed to have no problem with that design is a problem not just for the commission but for preservationists and historic districts generally. That the LPC last July approved a more recent, traditional design by HS Jessup Architecture is to its credit, but the approval was immediately criticized by the Historic Districts Council:

HDC finds that while the proposed design is not offensive and would be constructed of appropriate materials, it raises the question of whether it is appropriate to construct faux historic houses in historic districts. Introducing a design that is of our time or replicating the house that originally stood here would be acceptable strategies, but this house, while thoughtfully picking up details found in the neighborhood, does neither. The house might look like it has always been here, but we are not sure that would be an honest approach.

Friends of the Upper East Side Historic Districts seconded the HDC critique, but with a twist, adding that it may be a missed opportunity for a more creative design:

[FUESHD] has spoken out in the past about ersatz historic facades, and although this building is not an exact copy of a historic building, it closely resembles one and could be seen as a very literal adaptation. This site could be an opportunity to take a more contemporary approach.

The Root of the Argument

So this group is not only against exact copies of previous structures but against anything a passerby might think is old.

Such blind adherence to decades’ old modernist dogma raises the question of what preservation is all about. Does Manhattan or any historic neighborhood exist for the benefit of the people who live and work there, or is it a museum in which what is built is determined by a curator’s diktat? Preservationists should embrace new architecture in traditional styles because cities can and should change. But change need not poke folks in the eye. New traditional work is a strategy for embracing change without placing historical character at risk. Historical character, not just old buildings, is what preservationists should protect.

We are often warned that cities are not and should not be museums – mostly by architects and architectural historians who oppose new traditional architecture because it does not “reflect our time.” But can architects be trusted to determine how concrete, steel and glass express “our time” when historians themselves cannot even assess an era’s meaning with the perspective of decades or more?

On the other hand, if it may be said that “our time” is one of stress and discord, should architecture strive to reflect it? Obviously not, or so you would think. To pick up a long discarded modernist mantra – and a rising preservationist mantra – architecture should instead be part of the cure. It should not be fashionable to design buildings that stress us out. Isn’t our era doing enough of that itself?

Architects and preservationists who continue to embrace this “of our time” bugaboo are guilty of perpetuating not just an era but an error. Preservationists should look, rather, with favor on the proposed new building at 34 East 62nd St.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.