Ken Follett

Time and the Encaustic Tile Vestibule

It was May 2014 when I first looked at the encaustic tile vestibule floor at 129 West 78 Street in Manhattan. The townhouse had originally been built by Raphael Guastavino in 1886 and had undergone a comprehensive restoration just prior to our involvement. It was not until March 2018 that we finished the installation.

The area of the floor measured 2x 5 ft., 10 square feet. I am not in the tile business, but I am known for tinkering around with odd small projects. I was tempted by the challenge, by the history of the property, by the enthusiasm of the owner, and by the chance to work with the restoration architect with whom we have enjoyed a number of heritage projects.

The design is a mix of ornamental tiles with a majority of monochrome colors. Blue, white, orange, and several shades of brown. The tiles were manufactured by the American Encaustic Tile Company in Zanesville, OH.

First task was removal of the tile. Over the years there had been several butchered jobs of fixing, because of which some areas of the tile came up intact, while other areas, which were held in place with a hard mortar, were not so fortunate. We ended up with a jumble of pieces of tile. All of the pieces were carefully cleaned of mortar and soiling -- cleaned several times. The assembly quickly became a headache of a puzzle. For tile that was missing I temporarily made full-size pieces out of poplar wood. Once they were laid out on the workbench, it was easier to wrap our heads around the object at hand.

Our task was to locate encaustic tile to match the existing. We spent several months looking around, asking around, wandering around but were not able to locate a match. It was suggested that we go to Ohio and dig around, or to New Orleans and explore architectural remnant shops. Travel was way out of budget, and we were supposed to be making a semblance of a living with our work. We also experimented with several options to replicate the tile -- short of going into the encaustic tile business. If the owner had not decided to sell the property we might be still looking.

In the end the design compromise was to select a new gray porcelain tile that would accent but not overwhelm the underlying original design. Procuring that specified tile took an entire day of travel. Then dealing with the new tile became an issue in itself. It is more difficult to cut porcelain tile than ceramic tile. This was news to us. The gray tile was also thinner.

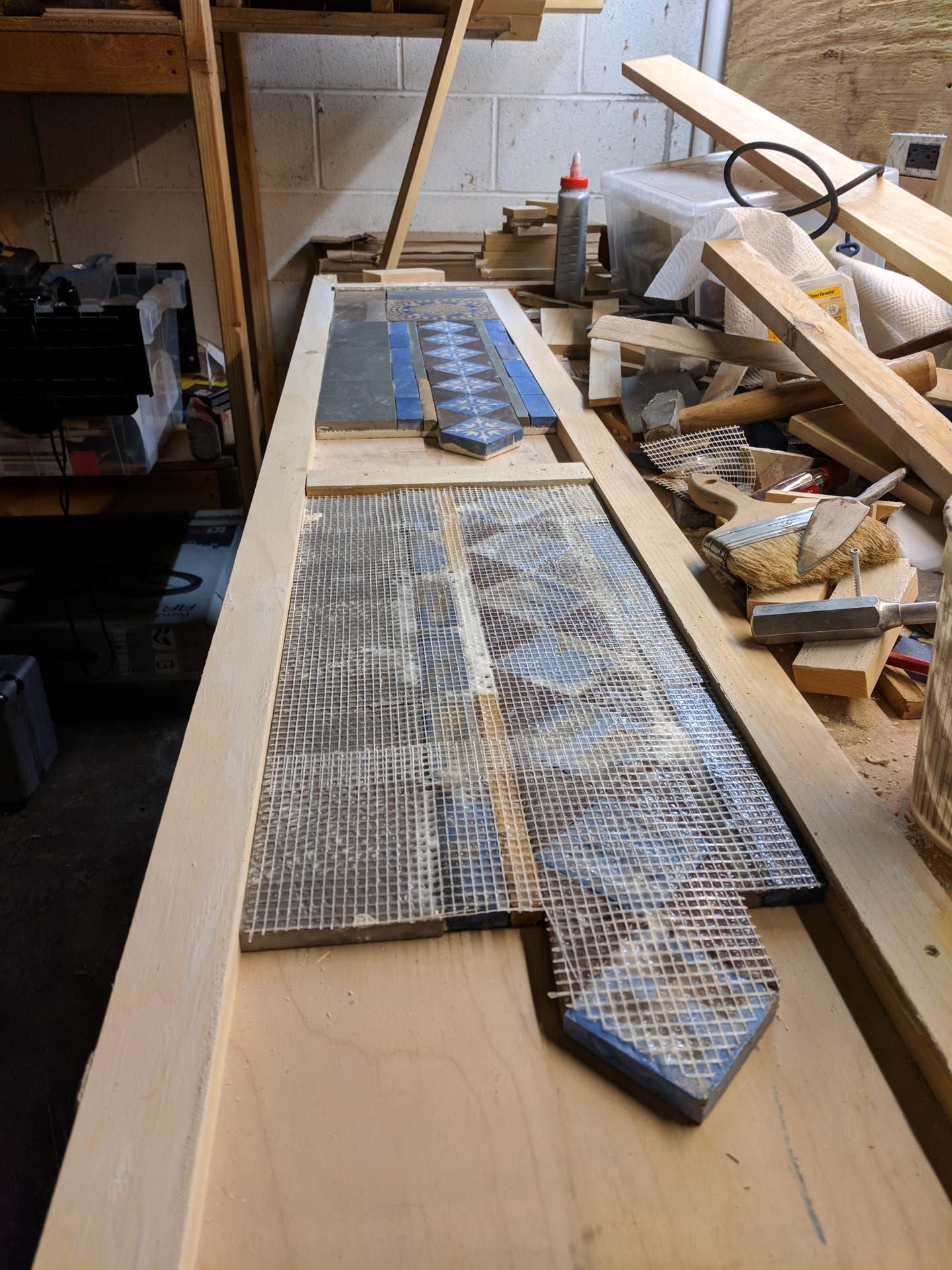

We wanted to reduce the amount of time spent in the field for installation. This is an approach that one gets used to when you work in New York City, particularly when the task is in a place where people will want to walk sooner rather than later. So we opted to make panels of the tile. For this we glued the tile to a nylon mesh. Each time we made a step forward, we ran into another challenge. In this case we had four thicknesses of tile. Our solution was to lay the tile face down within a frame and then to glue the mesh to it. But the mesh would not support the varied thicknesses, so we applied a leveling coat of fiberglass-reinforced mortar. In setting the tile face down we were working blind, and in a few cases we had to start over or make delicate modifications.

With the original floor the tiles were exact dimension and there was no space between them. Contemporary tile floors have grout lines. This meant setting the panels together very tight another --headache and a half. I was sometimes tempted to return the mess of tile and tell everyone that I could not handle it.

The tile panels were laid in a natural hydraulic lime mortar bed and then, once set given, a dark gray sandless grout. Discrepancies slowly dissolved, but I had looked at the tile for so long that every hair of a line stood out for me. I wanted it to be smooth enough to roll marbles on. Curiously, fitting a tile floor into such a small vestibule space between two sets of doors also means that you have to sit on the work in progress. When I was able to stand up and step back it looked fairly decent. The owner was very happy with the result.

The architect for the project was Zach Watson Rice. For more information, see Christopher Gray’s article in the New York Times,

Ken Follett is a founding member and 1st past president of the Preservation Trades Network as well as a longtime member of APTI and APT Northeast. Based in Putnam County, NY, his work is primarily in the NY/CT/NJ region with occasional stints in places such as Washington, DC, and Coloma, CA. His trade background is in masonry with an emphasis on playing with stone. Beyond stone, Ken has several decades of contract experience in project estimating, administration and management. Most notably in terms of education was his two and a half years as clerk-of-the-works on a $20M redevelopment project in Harlem for the NYC Transit Authority.

Currently Ken works in partnership with his son David Follett to provide in-field support services to structural engineers, architects and conservators in their design investigations of existing and historic structures. As a hands-on project consultant, Ken assists project teams in resolution of heritage conservation problems, most recently to resolve a project-killing issue for the award winning Eberhard Pencil Factory buildings at 58 Kent Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Ken also gets involved in small projects, such as deconstructing and reconstructing a Stanford White fireplace, designated mason in a Guastavino tile vault workshop, righting a tipped cemetery obelisk, or matching an existing custom stucco recipe. Ken also works with heritage contractors as well as materials suppliers, assisting them in their business development.

For eighteen years Ken was executive vice-president of a specialty historic restoration contracting firm in Brooklyn, NY. In the role of contractor Ken was responsible for the negotiation, planning and project management (for which Christian & Son was a team member) to relocate Thomas Edison’s #11 laboratory building from the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI, to its original site in West Orange, NJ. Of similar note was assisting the design investigation team for the Edison Memorial Tower in Menlo Park, NJ (a John Early concrete panel structure). He was also involved in the preconstruction and probe investigation activities for both the New Amsterdam Theater and the Grand Central Retail Redevelopment projects in NYC. Another project of note, involving public art, was the demounting and conservation of the Paul Manship Medallions from the NY Coliseum that were relocated and mounted at the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel Ventilation Building in Manhattan at the north side of Battery Park. Ken was the contractor and project manager for the multiple award winning exterior restoration of the Barnes & Noble corporate headquarters at the north end of Union Square in Manhattan, New York.

As a writer Ken has over the years published in a number of venues including Traditional Building, Building Renovation, CRM, APT Bulletin and APT Communiqué. Otherwise Ken speaks in public rarely, prefers to encourage and enable the more bold and outspoken, and even more rarely will direct a workshop (estimating for heritage conservation work)… though he has organized quite a few workshop and work experiences for others.

Experienced in contract procedure with the following public agencies: NYC Historic House Trust, GSA, U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, US Coast Guard, National Park Service, FDA, HUD, NYCTA, MTA Bridges & Tunnels, NYC DDC, and NYC Parks.