Clem Labine

Commission Tells Historic Districts: Forget Your Special Character!

Preservationists who believe the duty of landmark commissions is to preserve the special character of historic districts have been dealt another blow. An amazing 9-0 decision by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission has shown once again that the commission – like many similar review boards across the U.S. – functions like an architectural awards jury when it comes to additions and infill construction. Similar to their peers everywhere, commission members seem unwilling or unable to evaluate projects on the impact they’ll have on the historic character of the entire district.

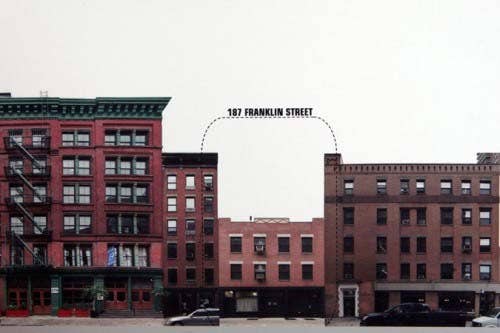

The project currently at issue is the addition of two stories onto an existing three-story building in New York’s Tribeca West Historic District. Rather than consider the project in light of its effect on the entire district, the members seemed to focus primarily on design issues of the proposed new façade. And in so doing, they have implicitly applied a simplistic interpretation of the Secretary of the Interior’s Standard #9: “New work will be differentiated from the old.”

Standard #9 "promote[s] radical contrast, rather than aesthetic wholeness"

The design for the proposed addition was vigorously opposed by New York City’s Historic Districts Council on the grounds that the façade was unsympathetic to the existing character of the neighborhood. But commission members brushed aside these objections, using words like "smart,” “delirious,” “exciting,” “robust and inventive” to laud the proposed new façade. The commission's chairman, Robert Tierney, went so far as to enthuse: “It actually enhances the richness of the district.” It’s a remark that makes sense only if the commission’s purpose is to promote radical contrast, rather than aesthetic wholeness, in the district.

The contradiction between the Landmarks Commission’s fixation on the character of individual buildings as opposed to entire districts is best illustrated by the commission’s regulations on windows. If a building owner in a historic district wants to replace windows, there is a highly complex permit-and-approval process that gets down to the level of regulating muntin profiles.

Having gone to this degree of detail to protect the character of existing buildings, it seems ludicrous (to this writer at least) that the commission imposes no such tests on the effect that additions and infill construction will have on the character of the entire district. Instead, approvals on additions and new construction seem to rest on the architectural tastes of commission members. And for most new projects, current commission members seem to favor Modernist styles, regardless of context.

Over several decades, whim-of-the-moment decision-making about additions and infill construction will inevitably degrade the special character of the historic districts that led them to be designated in the first place. One may well ask of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission – and many design review boards like it across the country: Precisely what is it that you are preserving?

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.