Vincent Michael

The Authenticity of Materials

In restoring historic buildings we strive for authenticity to the greatest extent possible, and one of our measures of authenticity is material. We are loath to replace a wooden window with a metal or plastic one. We tend to treasure historic brick or terra cotta and we value the original milled finish of quarter-sawn oak.

While our instinct for authenticity in materials is laudable, in order to make the best choices in rehabilitation, we need to be careful about three things. First, it is important to remember that our own aesthetics – like the beauty of quarter-sawn oak – were not necessarily shared by our 18th and 19th-century predecessors. Second, modern materials and products are not necessarily equivalent to their 18th and 19th-century predecessors, and often inferior. Third, technological advances sometimes give us a new material that is superior or more durable than the original. Let’s look at an example or two of each.

I worked for years in the Monadnock Building in Chicago, designed between 1889 and 1891. The large wooden windows in every office were faux-grained, meaning they were painted to look like another type of wood. This was the aesthetic before the 20 century. The Steves Homestead Museum in San Antonio is an 1876 Second Empire gem built by a lumber baron – and he faux-grained all of the wood, not because it was cheap or low-quality, but simply because it would not occur to a Victorian to find aesthetic value in unfinished wood.

What we consider a “faux” or fake finish was simply considered sophisticated taste and good design. Mount Vernon has a wood exterior painted and textured to resemble ashlar stone blocks. Many years ago I worked with students at Portumna Castle in Galway Ireland, a 1618 manor house. The stone castle was constructed with structural stone quoins at the corner, and then the entire façade was rendered with a thin layer and new quoins – not matching the actual, real structural quoins – were painted and carved into the render. That was good taste and good design. Buildings did not go about unclothed.

Now, part of the reason we valorize original materials is because they were often better: original growth wood; newly quarried stone; dense 19th-century brick; real plate glass and 1930s steel windows with a profile than comes from rolling the steel more times than anyone will today. People fret about having to buy wood windows, but the reality is that what we really want to preserve is not “wood” but the dense high-quality wood in the original windows, not the knotty fast-growing and fast-warping wood of today. For decades I have watched Chicago brick buildings demolished and their brick bundled for re-use because they don’t make it like they used to.

So how come our guidance does not privilege original materials? Secretary of the Interior Standard #6 for Rehabilitation states in part “Where the severity of deterioration requires replacement of a distinctive feature, the new feature shall match the old in design, color, texture, and other visual qualities and, where possible, materials.” The material itself takes a position behind visual qualities.

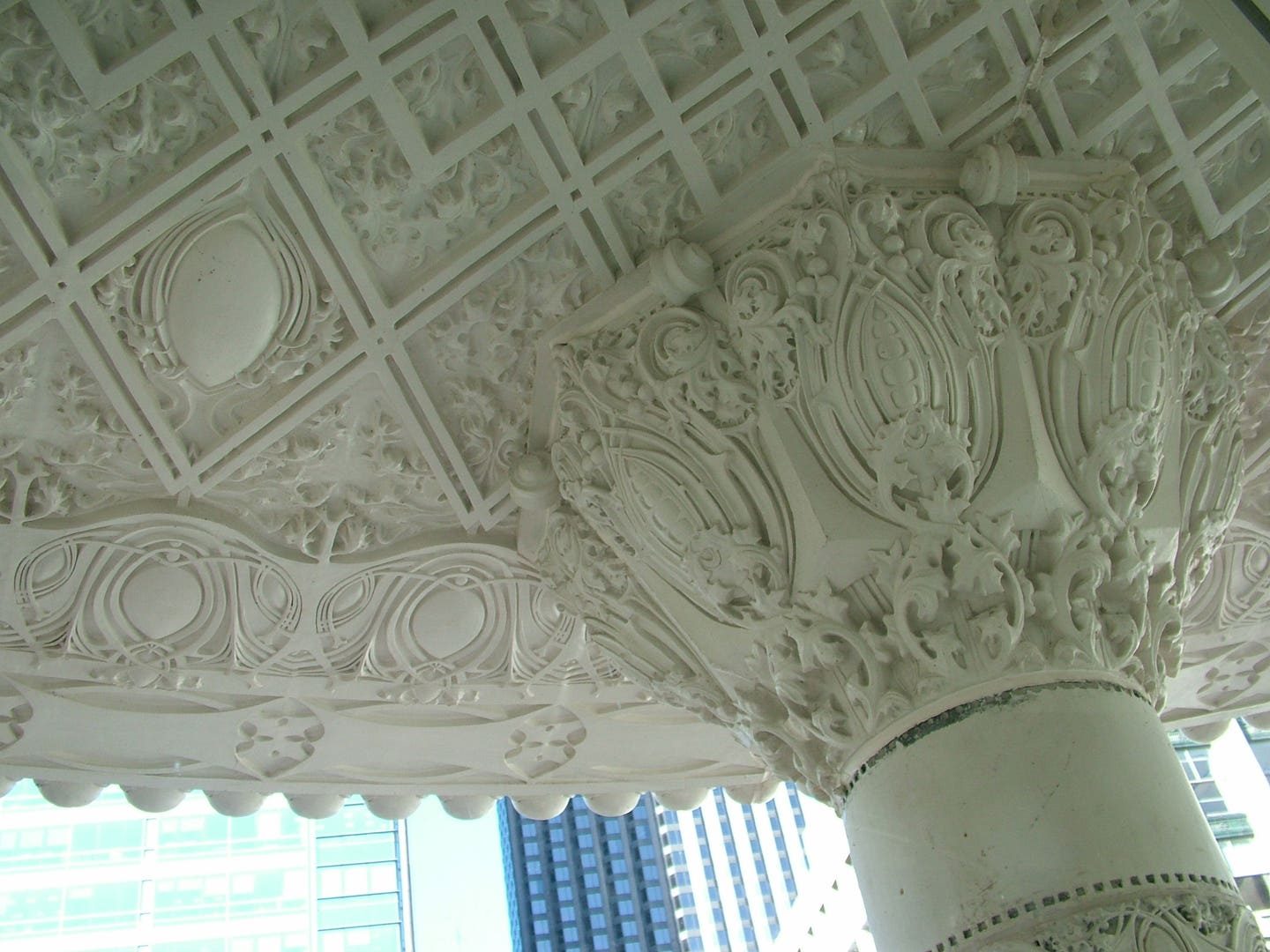

This brings us to the third point. Sometimes, technology is better. Several Chicago skyscrapers have seen their cornices restored in recent years. These restorations were not done in the original terra cotta, but in lighter and more durable glass-fiber-reinforced concrete, hung with more rust-resistant metals. They meet Standard #6 in terms of appearance but actually will perform better over time thanks to advances in materials.

The most important thing to remember about Standard #6 is the opening phrase: “Deteriorated historic features will be repaired rather than replaced.” Fix it. Don’t even start thinking about replacement materials until you have done that. Rehabilitation is a process and you can’t skip a step.

Vincent L. Michael, PhD is an international thought leader, writer, expert consultant and speaker in heritage preservation. Now completing his 9th year as a Trustee of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Vince served from 2012 to 2015 as Executive Director of the Global Heritage Fund in Palo Alto, California, and prior to that as John H. Bryan Chair of Historic Preservation at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

To find out more, you can visit his web site: www.vincemichael.com