David Brussat

Architecture as Haute Couture

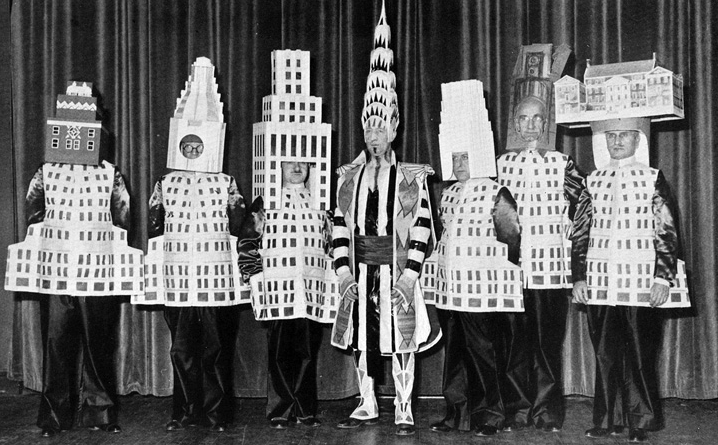

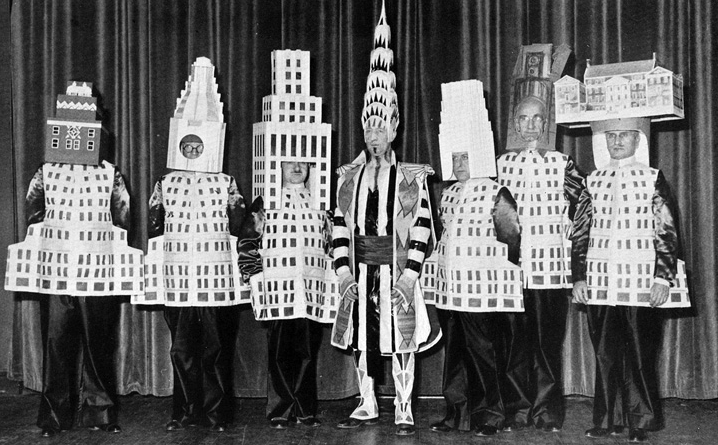

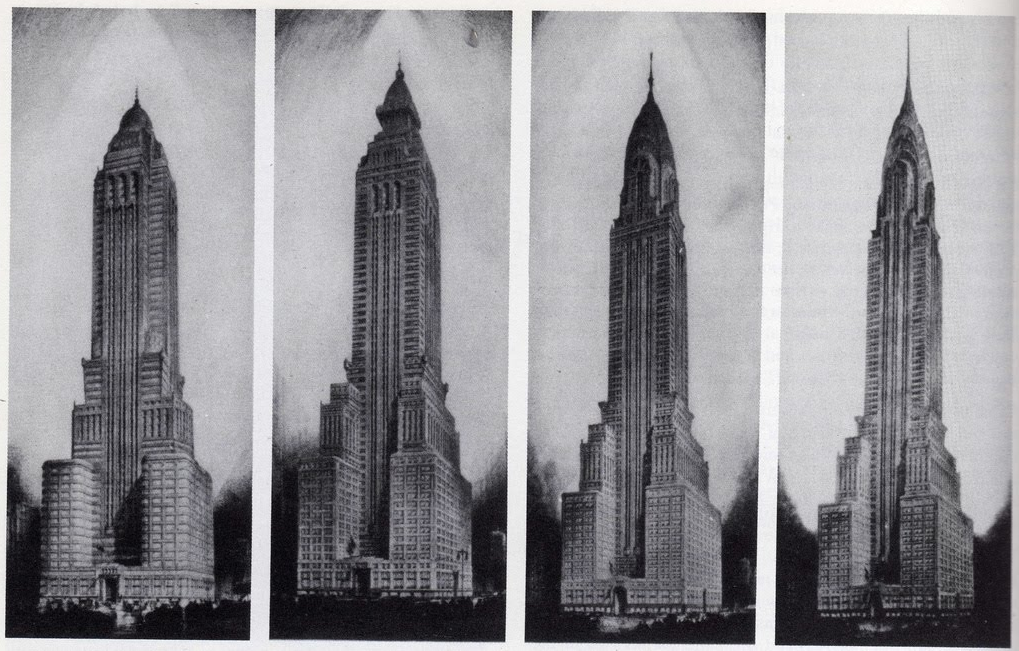

Long ago, I read Higher, by Neal Bascomb, about the race to construct the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building. A picture of architect William Van Alen at the 1931 Beaux Arts Ball wearing a costume to honor his creation, the Chrysler Building, came to mind back then as I prepared to deliver a lecture. My theme was architecture and ladies’ fashions.

To be frank, it was a last-minute, in-the-shower sort of an idea, but I went with it anyway, and it seemed to amuse the indulgent ladies listening at the Brown Faculty Club. “Only a man could come up with a nutty idea like that,” they were probably saying to themselves. But as I spoke, the idea kept growing on me.

Look at the photo of Van Alen, center, with the Chrysler Building’s crown on his head. Lovely as the pre-modernist Art Deco building is, no man would wear it as a hat in real life. And no woman would wear such a hat in the real world — unless she were a model at a fashion show of haute couture.

Fashions in dress have changed greatly, if slowly, over the centuries. People have always worn clothes much like the clothes other people wear. More money buys nicer clothes, and while women’s fashions might diverge more than men’s from basic form, a shirt is a shirt and a dress is a dress. Except on the runway of a fashion show of haute couture.

Likewise, houses have changed greatly, but slowly, over the centuries. People have built, bought or rented houses they could afford, houses much like the houses sought by other people. You could always locate the front door effortlessly. At levels where people pay for their own accommodations, modern architecture has never caught on.

Of more substantial buildings, the same pattern prevailed – until the middle of the 20th century, when modern architecture suddenly took over among buildings chosen by committee.

From Bauhaus to Our House

Tom Wolfe described this shift in From Bauhaus to Our House:

But after 1945 our plutocrats, bureaucrats, board chairmen, CEOs, commissioners, and college presidents undergo an inexplicable change. They become diffident and reticent. All at once they are willing to accept that glass of ice water in the face, that bracing slap across the mouth, that reprimand for the fat on one’s bourgeois soul, known as modern architecture.

And yet I don’t recall ever seeing modern architecture compared to haute couture. Maybe that’s because the comparison never really made that much sense until recently. As long as modern architecture was about “utility,” “purity of line,” and that sort of thing, it was merely boring. A glass box was a glass box. All the glass boxes on Manhattan’s Park Avenue look pretty much the same, including the Seagram Building (1958), the big daddy of glass boxes.

But in the 1990s, modern architects started to don new party hats. Each had to be not just different but way different. “Egotecture,” it was called. The buildings of Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Rafael Moneo, Renzo Piano, Sir Norman Foster, the late Zaha Hadid, etc., look nothing like other buildings, or, for that matter, like buildings at all.

Increasingly, they resemble the sort of clothing that you snicker at when you see the most haute of haute fashion shows on TV. Deconstructivism, Minimalism, Blobism, the new architectural styles roll out, each one sillier than the one before, winking and smirking their way down the runway (or rather, alas, down the street) as the public tries to tune out. They are not architecture but haute couture.

In spirit, they recall Philip Johnson’s Glass House (1939), his own residence in New Canaan, Conn., of which he said, “Sleep here? I could never sleep in this house. That’s why I built the guest house.”

Look again at the photo of William Van Alen in his hat. The oddest thing about it is that the funny hat sits on top of the head of a man. Have you ever seen a hat like that on a man? Of course not. (Now isn’t the time to mention the Vatican. Or the Super Bowl.) Men would never put up with such tomfoolery. Even if women could afford it, most would not be seen in most of the ridiculous “clothes” worn on the runways of New York, Paris or Milan. And if they did, men would not put up with it.

But in architecture, the “slap across the mouth” is not only accepted but de rigueur. And the public puts up with it — so far. Modernism has finally achieved the feminization of architecture. If we could only get more actual women (but please, not Zaha Hadid!) to be architects, maybe architecture would make some sense again.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.