David Brussat

When Architectural Renderings Bend the Truth

These days, it is often fair to wonder whether the renderings for an architectural project are meant to reveal what it will look like or to cover it up.

The other day I took a Jane’s Walk tour of Benefit Street - Providence’s Mile of History. Later in the day I guided my own Jane’s Walk tour of the Providence waterfront. Jane’s Walks honor Jane Jacobs, the author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), who saw more clearly than anyone how the urban-renewal policies of the 1950s were killing urban America.

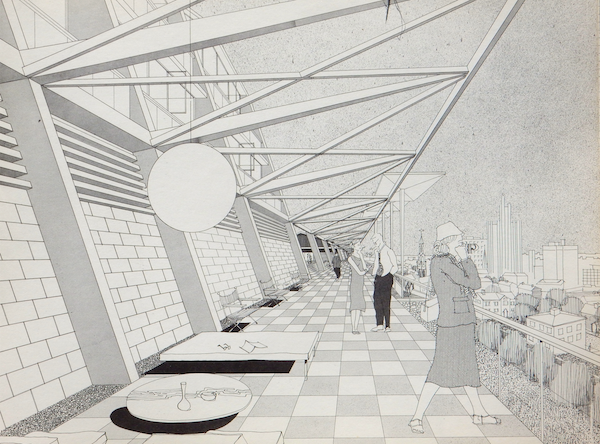

Tim More, who guided the tour of Benefit Street, shows illustrations from the College Hill Study (1959), designed to “preserve” Benefit and other parts of College Hill, where Brown University, Rhode Island School of Design, and a pricey historic neighborhood are located across the Providence River from downtown. Actually, the plan was designed to use preservation as an excuse to introduce modern architecture into the historic district. Tim showed an illustration of a 19-story glass tower planned for Benefit, which elicited snickers and boos from those on the tour, and of a hotel also planned - or so I thought - for Benefit. The rendering of the hotel featured a stark modernistic deck overlooking the historic houses of Benefit.

Tim said he believed this was to have been located just beneath the overlook of Prospect Terrace, a small park with a great view of the city. For years I’d believed the same. You could tell the hotel terrace looked down upon Benefit and to the city beyond - same as the view from Prospect Terrace itself. Yet in the rendering, there were two more stories of hotel rooms above the hotel terrace, obscuring the park above, with its statue of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams, who was looking out toward the city in a posture that might read as “Disco Roger.”

It seemed as if the artist who drew the rendering didn’t really want people to know how close the hotel came to degrading the view from the park. I assume that the illustrator would have been following instructions of the planners rather than, on his own volition, deceiving future readers of the plan.

My longtime assumption about the location of the hotel terrace was shaken when the Providence Preservation Society, a participant in the College Hill Study back in the 1950s, asked me in 2017 to serve on a panel assessing illustrations from the study. Notes distributed to assist the panelists assessing the rendering of the hotel terrace marked its location at Benefit and South Court streets. The hotel was to be called the Golden Ball Inn II, after the original Golden Ball Inn, which opened in 1784 at Benefit and South Court. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette all stayed there. It was razed in the 1940s.

So on the basis of the notes of the rendering, I rebooted my assumption of the location of the hotel. But after Tim More again stated that it was to have been beneath Prospect Terrace, I looked more closely at the plan in the College Hill Study document. From that, it appeared as if the new hotel was going to be a vast enterprise that stretched between both points. In other words, the new hotel was all over the place. Who knew how many historic houses it would doom.

In the end, very little came of the College Hill Plan, but for decades the Providence Preservation Society treated it as a major victory for historic preservation, despite the intended demolition of many historic houses, deemed substandard by the shoddy application of federal housing codes, presumably beyond restoration. They were to be replaced by the modern architecture then (and still) in vogue. Gladly, most of the College Hill Study’s recommendations were ignored, as was an even more destructive plan, Downtown Providence 1970, issued in 1961.

It turned out that in relatively short order on College Hill and over a longer period downtown, market forces and private enterprise saw to the preservation, restoration or renovation of most of the houses and buildings intended for demolition, and many more. With successful revitalization, Providence’s downtown and College Hill are uniquely beautiful examples of urban America at its best.

So it turns out that dodgy renderings can fool all the people some of the time and some of the people all of the time, but they cannot fool all the people all the time.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.