The Forum

A Vision for Civic Conservation

By Jenny Bevan

Because decades of car-centric planning and internationalist architecture has failed to produce places of local character, the demand for walkable, charming places outpaces supply. And since globalized finance requires a homogenized building product, what gets built in one place must be the same as what gets built everywhere else, be it in Dallas, Columbus or Charleston.

Consequently, contemporary developments within and adjacent to historic districts are often incompatible with existing neighborhoods. The ensuing homogenization is not simply about aesthetics – it is a threat to the social, environmental and economic sustainability of our communities, for local building cultures not only pass down the knowledge and skills which make possible the continued creation of places of distinctive character, they also contribute significantly to local economies. Globalized finance relies on industrialized building systems that neither employ as many craftsmen, nor endure long enough to become assets to the community in the way that old buildings do.

Preservation – the primary means of public advocacy in planning – is poised to help steer development to better suit local urban and architectural patterns. But having grown into an academic discipline separate from those of planning and architecture, preservation now operates not under a theory of city-building, but under a theory of history, a theory that discourages the continued use of successful historic patterns of settlement, a theory that alienates us from the very skills, knowledge, and principles that produced such preservation-worthy and in-demand neighborhoods in the first place.

What is needed now is for preservation to develop tools to advocate for the only viable solution to relieving the pent-up demand for walkable, charming and locally-distinctive places, which is to build more walkable, charming and locally-distinctive places. To this end, we created CivicConservation.org, which proposes a new direction in preservation and provides a framework of guiding principles to address progress and growth. We are also calling for a new preservation charter, one that reflects lessons learned from Modernism, lessons from decades of application of the Venice Charter, and lessons from new traditional urbanism and architecture.

At the core of Civic Conservation is the belief that we should strive to live harmoniously with nature

The health and sustainability of the city depends on the health and sustainability of the countryside, and vice versa. Today we are accustomed to the idea that local agricultural and culinary traditions can provide more sustainable alternatives to the unhealthy and unsustainable industrialized food systems. Yet when it comes to architecture, planning and construction, the unhealthy, unsustainable industrialized building systems still dominate; traditional solutions are relegated solely to the rehabilitation of old buildings. Civic Conservation aims to change this.

Inspired by those grass-roots preservationists who established the first historic districts and saw their cities as living ensembles that offer locally distinctive alternatives to the internationalist projects then growing in popularity among architects, Civic Conservation promotes diversity and true plurality of choice by treating historic districts not as museums, but as models for future growth and development – bulwarks against globalized homogeneity. And Civic Conservation connects craftsmen with architects, planners and others who, although working at different scales, have a shared vision for more economically sustainable, durable and locally distinctive building cultures.

The primary components that contribute to the characteristics of a place are its planning, its architecture, and its local building and craft industries. Civic Conservation proposes, therefore, that the assessment of additions to historic districts be according to how well they conform to, integrate with, or enhance the local urban and architectural patterns, and by how well they engage with the local building economy. Because most historic districts were established before car-centric planning, generally speaking, the urbanism is walkable, the architecture is durable and locally adapted, and the construction methods have stood the test of time.

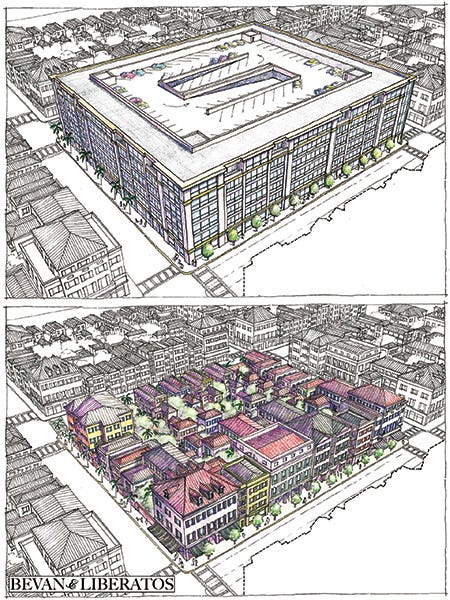

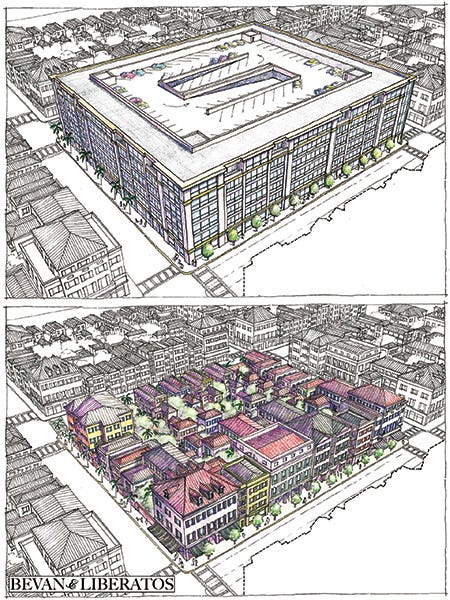

The images shown here are from a case study comparing Charleston’s unique urban and architectural patterns to those currently dominating Charleston’s larger planning applications. Two projects of equal footprints are compared: the upper image is based on proposed new “Texas donuts” or lined parking garages; the lower image is a Charleston-style block modeled on the district’s most successful existing fabric. Evaluation reveals that not only does the Charleston-style block accommodate the same number of bedrooms as the Texas donut (about 200), but it does so with buildings that are only two and three stories (compared to the donut’s six stories), while accommodating porches, gardens, trees and a permeability that takes advantage of breezes – a much more livable backdrop to life in a sub-tropical climate. And livability is an essential quality for a sustainable city.

Further analysis compares the differing effects on the local economy: the donut involves one contractor, one steel sub, one concrete sub, and laborers to assemble pre-manufactured building components, whereas the Charleston-style block is a model that enables many developers, many builders, many craftsmen. Whereas the donut typically has one owner and offers housing only for renters, the Charleston-style block has many owners and a greater diversity and flexibility of use: renters, homeowners, singles, families with children, shops schools. And because the donuts are built primarily for the purpose of short-term holding, the industrialized methods of curtain-wall construction result in mold, poor indoor air quality, and buildings with premature lifespans, typically lasting only 30-40 years before needing overhaul or replacement.

We invite you to see more at CivicConservation.org/casestudy and to add your name to the growing list of signers of the Vision for Civic Conservation page. Leave your email address, and you will be kept up to date with news about the project for a new preservation charter. TB

Jenny Bevan and Christopher Liberatos are the principals of the design firm, Bevan & Liberatos, based in Charleston, SC, and are the authors of A Vision for Civic Conservation, found at civicconservation.org.