David Brussat

Modernist Hubris May Hasten Architecture’s “Trump Moment”

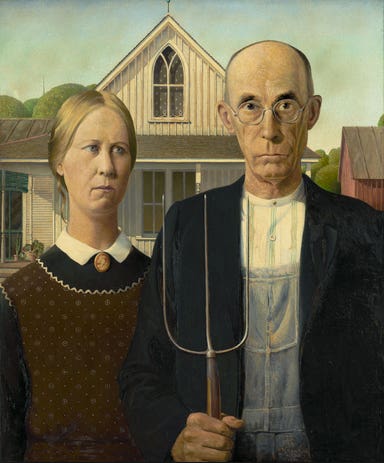

Will the public ever pick up its pitchforks?

Duo Dickinson has a brilliant essay - "Will Architecture Have Its Donald Trump Moment?" - on the website Common/Edge. He compares the Republican establishment in politics to the modernist establishment in architecture. He compares those carrying pitchforks in the armies of Trump and Sanders to the masses pounding sand as they contemplate the inexplicable horror of the built environment wrought by modern architecture. He begins:

There are two architectures. Not officially, yet, but the perception is real and growing that there is an architectural apartheid. There is an “inside”(the AIA, academia, mainstream journalism) and an “outside”(building, client-serving, context-accommodating architects).

But Dickinson says it has little to do with style – traditional versus modernist – and then his essay segues into concern for the average architect and his travails in a field dominated by starchitects and the starchitecture-centered American Institute of Architects.

The entire essay is a deft dodging of the fact that it is indeed all about style. Here is the moment when Dickinson's fine essay trips up on its refusal acknowledge the applicability of his own observations:

It’s simplistic to say that it’s a style split: obviously in promoted architectural aesthetics “Elite=Modern,”but the disaffection in my profession … is more about the invisibility of everything except the “cutting edge.”

And yet the fact that the public prefers houses that look like houses, churches that look like churches, and museums that look like museums introduces an impossible degree of distortion into everything about the field of architecture. This makes it harder for the typical practice to operate. Decisions made by architects and firms must discount reality from their business models. Architect wannabes have little alternative to a modernist education, little prospect for jobs at firms where they can use what they were taught, and nothing to look forward to but a widespread dislike of their work, whether they get a job with a modernist firm or with one of the many that build spec housing and spec commercial. Such spec architecture is often "bad trad" because the firms that build it must hire from a pool of graduates who were not allowed to learn how to produce "good trad" – only how to disdain it.

Most architects feel dissed because most people feel dissed by architecture. In politics, there is recourse to an electoral process. No such luck in architecture.

Agreeing to Disagree on the Eternal Verities

Paul Ranogajec and I have gone back and forth since his Forum in the last issue, not just in my reply to him and his latest reply to me, but in a long thread on the TradArch listserv. Here it continues. We have agreed to disagree, but several of his errors in characterizing my blog’s reply illustrate not just that disagreement is inevitable but that it is necessary if classicism is to avoid the muddle of contemporary thought that Paul believes classicists should engage.

I am sure Paul admires my “passion” with a ten-foot pole. In his mind, erudition trumps passion all the time. The latest scholarship always overtakes the eternal verities. He bridles at my alleged “us-versus-them rhetoric,” suggesting that for me “it is either modernism or classicism.” I have not said that. I have merely asserted my belief that for both architecture and society classicism’s essential simplicity is “a better operating system” than the complexity and confusion of Paul’s “current intellectual milieu.”

Paul holds an idea of the “timeless classical” as a sort of thoughtlessness, a self-imposed ignorance of the current intellectual milieu. No, it is quite the reverse – a thoughtfulness that has sifted that milieu and found much of it wanting. That is not to ignore Michel Foucault and Martha Nussbaum; it is to treat them seriously, to examine them closely and, with all due respect, to prefer “eternal verities” and “basic human instincts” as better guides for architecture and for society.

I pointed out that modern researchers have found a scientific basis for the popular preference for tradition over modernism in architecture. Paul asks: “Did I suggest that we not look at that type of work?” No, you did not. You did assert, however, that classicists ignore contemporary thinkers, and I brought them up to say it is not so. Even if we do ignore Foucault and Nussbaum (and many others), Christopher Alexander and Nikos Salingaros are no less contemporary thinkers than they are.

My point in objecting to Paul’s original Forum was that, to the extent that classicists prefer maintaining allegiance to their eternal verities and basic human instincts, they are making judgments no less valid for being more passionate, or intuitive, than erudite. Paul’s thoughts are highly intelligent, but wisdom demands more, and nothing he writes has shaken my belief that the “timeless classical” – even as misconstrued by Paul – is the wiser course for classicism to pursue.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.