Profiles

Atkin Olshin Schade Expands into the Southwest

What the built environment of North America may lack in antiquity, it certainly makes up for in sheer size and regional diversity. How then does an architectural firm in search of new challenges straddle not only a growing range of project areas, but starkly different climates – and even cultures? There's no one answer, but an interesting example of how it can work is Atkin Olshin Schade Architects of Philadelphia and Santa Fe, NM. Rooted in a city as rich in landmark buildings and revered designers as it is East Coast and urban, the firm has branched out to cover not only "green building" and historic forts but even the Native American architecture of the Southwest.

Like many firms, Atkin Olshin Shade Architects has modest beginnings – in fact about as modest as can be. "Tony Atkin, one of the partners, was originally a sole practitioner," says principal Michael Schade, AIA, LEED AP, "and he pretty much started out doing whatever work he could get – mostly residential and smaller-scale projects." That was in 1979, and today Atkin, now an AIA Fellow and regular teacher of graduate design studios and seminars at the University of Pennsylvania and other universities, remains a principal and the lead designer of the 25-person office. In 1986 he was joined by Sam Olshin, a design student of Atkin's while in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, who became a partner in 1995 and is the lead designer in the Philadelphia office.

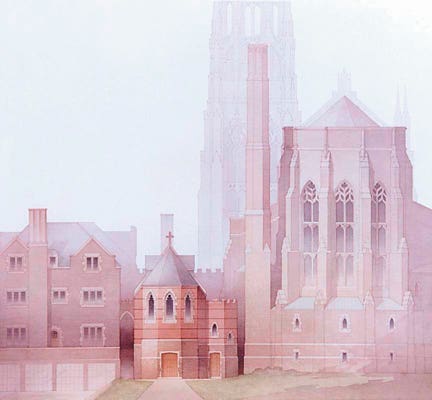

Early on, the fledgling office scored something of a bullseye with a project that presaged much future work. "What really put the firm on the map," says Schade, "was winning a design citation fromProgressive Architecture magazine in 1983." That design was a small chapel for the Cathedral of Christ the King, in Hamilton, Ontario, whose interior had been badly damaged in a 1981 fire. Not a bad coup for a firm barely four years old, but even more of a feat given the source. Until its demise in 1996,Progressive Architecture had been the standard bearer for outside-of-the-box design and construction, and its awards (which live on with successor magazines) recognize "risk-taking practitioners and progress in the field of architecture."

Though dedicated in 1933, the Cathedral is a textbook example of a medieval church rendered in highly detailed limestone with interiors that have been described as pure 13th-century English Gothic. Notes Schade, "In the early 1980s, Progressive Architecture and most architects' work was decidedly contemporary and postmodern, so Tony's very contexual design and careful detail stood out for the jury, which included Charles Moore." The award piqued wide interest from a variety of quarters – including other church groups – and led to many collaborations that AOS still enjoys. Other important early projects were an addition to the Rhode Island School of Design and the Renfrew Center in Philadelphia. Renfrew, being both very traditional and very modern, won them another nod from Progressive Architecture in 1985.

Cap, Gown and CAD

Religious buildings remain an important part of the firm's practice – some 30 percent – but they are now joined by museums, adaptive reuse, historic preservation projects and a great deal of college and university work. Says Schade, "Several institutions have become key clients; Dartmouth College and the University of Pennsylvania, where we have done four major projects apiece, are two of the most important." He adds, "It's really satisfying to build a successful relationship that can continue into future work. There's a lot of understanding about what they're expecting from us – they know us and our work, we know their institutional needs and requirements."

Compared to some firms who may follow a trend in campus work – say, adaptive reuse of old dorms into computer labs – the projects AOS sees vary with every commission. "It's a mix of renovation, new construction and preservation that stylistically runs the gamut from quite contemporary to very traditional," says Schade. He adds, "Our design philosophy has evolved to encompass both the influence of a building's preservation or context along with the deeper context of our clients and their projects – including their region, climate, history and culture. Our work and our responses are quite varied."

A case in point is the new Penn Museum Mainwaring Wing at the University of Pennsylvania. Completed in 2002, this addition is the long-awaited capstone of an 1896 master plan that gives a state-of-the-art home to the collections of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, as well as office and workspace for the staff. Not surprisingly, the four-story building has its feet in two eras. Begun in 1899 as the Free Museum of Science and Art, the original buildings and plan were led by the celebrated architect Wilson Eyre, who chose the Northern Italian Renaissance style.

In the new wing, the northern and eastern facades extend the original building's proportions and materials, while also adopting details from the original building, such as the Arts & Crafts brickwork style. On the façade looking away from the courtyard, however, the building shifts gears by facing the structure with bronze panels framed in limestone and incorporating a street-level arcade. "It's very contextual on one side, quite contemporary on the other," explains associate Shawn Evans, AIA.

Another area of AOS's practice where traditional and contemporary often wind up back-to-back is the intersection of traditional and historic buildings with sustainable construction. Says Schade, "What interests us is looking at how traditional design elements – solar orientation, overhangs for sun control, passive ventilation and natural light – can be used in new, beneficial ways, how they can inform our architecture." But it's not just old ideas for new buildings; AOS also looks for ways to make existing buildings even more sustainable by improving the exterior envelope or installing more efficient lighting and mechanical systems.

Such melding often starts with the initial planning. In fact, Evans and Kristen Suzda, a LEED-accredited colleague in the office, created a matrix to help view existing buildings through the lens of determining what sustainable improvements are worth including. Says Schade, "We've learned that there's often a lot of overlap between sustainable building practices and preservation practices, but there will certainly be actions only good for preservation, or for sustainability, and not necessarily vice versa. The goal is to align them on a case-by-case basis."

Evans puts a finer edge on the point. "In determining preservation treatment recommendations," he says, "we may not choose the most sustainable patching compound, but we're going to choose the product that's best for the building's fabric." Windows, of course, can be right at the crux of such a balancing act. Says Evans, "We're working for our clients, but we're also trying to defend old windows when they are important to the building. I'm often explaining that an insulating glazing sandwich is only good as long as the sealants hold, and a more sustainable option may be exterior or interior storms that may be just as energy efficient and still preserve the character of the fabric."

Two recent additions to the Dartmouth College campus – Fahey and McLane Halls, undergraduate residences completed in 2006 – illustrate the commitment. Though the brick exteriors and copper-and-steel roofs blend effortlessly with the prim Georgian styling of the campus, they are also among the many sustainable and recycled building materials used in the project. Other features include radiant heating/cooling served by standing column wells for ground-source heat rejection, a highly insulated building envelope and energy-efficient mechanical equipment and light fixtures – "All the bells and whistles" in the words of Schade that recently earned the buildings LEED-Gold ratings.

Where the Buffalo Roam

The firm's preservation work is no less many-sided. "It ranges from critical repairs and rehabilitation, to the scholarly restoration of historic sites," says Evans. "Much of the latter has been military fort work, such as Fort Mifflin in Philadelphia, Fort Stanton in New Mexico, or Fort Apache in Arizona."

Evans explains that the firm is often called upon not just to conserve an historic edifice but also to do comprehensive master plans that include historic and cultural interpretation as well as preservation. "At many of these sites, the history of modification and the evolution of function is more significant than what the site originally was," notes Evans. He adds that, "A lot of our preservation work is about understanding the changes through time and then accommodating them – either as an historic site or in a fully functioning building."

Typical is the case of Fort Apache, which began in 1870 as a military outpost some 175 miles northeast of what is now Phoenix, but was converted to a Bureau of Indian Affairs school in the 1920s. The comprehensive master plan AOS is now working on not only includes preservation planning and assessing the conditions of the 24 historic buildings, but also evaluating the 288-acre site for interpretive and economic development possibilities for the White Mountain Apache Tribe, who regained ownership of the site following a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case.

All of which raises an inevitable question: What brings a firm with such solid footings in the land of the Quakers, to the Spanish Colonial mesas of New Mexico? According to Schade, "Tony Atkins grew up on a ranch in northern Arizona, so he has a love of the Southwest. After the firm got some work in the area, he decided to open a second office out there, and it has done quite well."

If there's a popular image of Santa Fe, it starts with a downtown brimming with earthy adobe walls and flat roofs resting on log beams called vigas. Though the city is 400 years-old this year, much of this Old Southwest ambiance has its source in a 1912 "pueblofication" of Victorian buildings calculated to make Santa Fe a tourist mecca by recapturing its historic character. Nontheless, there's much more to the town than reborn architecture. "Next to New York City," says Schade, "Santa Fe is the largest art market in the country, and since we do a fair amount of our work in museums, it's a great place to be in business."

Also not lost on the firm was their size advantage. "Around 2005, when we really focused on setting up the office," says Schade, "there were about 100 AIA members in Santa Fe but 85 firms." In other words, Santa Fe was a city of basically one-person firms. "So pretty soon we were able to stand out as a full-service practice with preservation, planning and architecture of all types on our resume."

In fact, the Santa Fe office has developed wonderful new types of work through Native American clients that have become a big component of the practice. Atkin began his career in the Southwest with work at Acoma and Zuni Pueblos, and Jamie Blosser, director of the Santa Fe office, has extensive experience with Native American communities. This has resulted in recent commissions for housing, museums, and even a fire station on tribal lands.

"One of the most interesting preservation projects from our Southwest office is the preservation plan and phased rehabilitation of the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, about half-way between Santa Fe and Taos," says Evans. "With help from the stimulus bill, we are poised to begin rehabilitation of 22 houses that may have components over 500 years old – surely the oldest housing investment by HUD in the country!"

Running a firm with two far-flung offices is challenging. The firm is dedicated to careful attention and response to local issues in every project while using expertise and talent built up over their years of practice. Just the same, Evans says, "We've been very careful about how we bring our expertise from the Philadelphia office into Santa Fe" or applying East-Coast solutions to the Southwest.

"It helps that we now have a well-established practice in New Mexico. Though we do have people who shuttle from one office to the other, most of our staff members in Santa Fe are from that part of the country," he adds. With clients who are Native American tribes, and therefore sovereign nations within the borders of the U.S., there's also the need for overlay of diplomacy and sensitivity that goes beyond the normal project. Says Evans, "We feel very privileged to be involved and, fortunately, Jamie Blosser actually worked for the Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo for a number of years, so we have started with a deep level of trust."

Par for the course, the project is proving to be as perplexing as it is fascinating. In trying to preserve and restore elements of the pueblo, AOS is dealing with a structure that existed hundreds of years before the advent of photography and there are only a few written records. But the puzzle is not all mechanical.

"What's interesting is the dilemma of having to meet the practical and cultural needs of the tribe, while also meeting the Secretary of the Interior's Standards, because of the federal funding," says Evans. "Especially since opening our Santa Fe office, we're all now operating with a higher awareness of how buildings – particularly building cultures that are regionally based – vary from climate to climate. In the process, we've learned a lot about Philadelphia too."

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.