Features

Book Review: Frank Lloyd Wright-From Within Outward

Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward

by Richard Cleary, Neil Levine, Mina Marefat, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Joseph M. Siry, Margo Stipe

Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York, NY; 2009

360 pp; hardcover; 318 color and b&w illustrations; $75

ISBN 978-0-8478-3262-0

Reviewed by Gordon Bock

Back around 1996 I had the honor of meeting Edgar Tafel, the architect who recorded his many experiences with Frank Lloyd Wright in the booksApprentice to Genius and About Wright. While chatting with Tafel about the Usonian Homes project, a neighborhood of Wrightian houses near where I grew up in the wilds of suburban New York, he paused to reflect and noted that "Wright is admired and revered today as he never was before."

Should there be any doubt that that awe has only grown in the decade since, we now have Frank Lloyd Wright: From Within Outward, published on the occasion of the 2009 Guggenheim Museum exhibition of the same name. While the oxymoronic title doesn't exactly hint at what's between the covers, it does have its logic. As Phil Allsop and Richard Armstrong explain in the preface, for Wright, "exterior form was an integral expression of the spaces within a building," or put more succinctly, he "designed his buildings from within outward."

Of course, the inevitable question is, does the world need yet another book on Frank Lloyd Wright? Fifty years after his death, is there really anything more to say, learn, or discover about the man who all but single-handedly put houses, then larger buildings and even cities, on the path to modernity? Judging by this book, there is indeed.

Though drawing on an exhibition – which coincidentally also celebrates the first half-century of one of Wright's most controversial commissions, the Guggenheim Museum – this is no mere catalog. Rather, it is comprised of four chapter-length essays, interspersed with photos new and archival that, according to Margo Stipe, "look at how Wright addressed the larger social context of the built environment."

One of the more interesting essays to me was "Frank Lloyd Wright and the Romance of the Master Builder" by Richard Cleary. It is axiomatic that drawing up brilliant buildings on paper is cool, but executing the plan is what counts and, apparently, Wright often wrestled with the crucial interface between architect and contractor.

At a time when the Greene brothers in Pasadena were enjoying a long relationship with Peter Hall, the builder who had the skills and sensitivity to execute their vision and level of finish, Wright was not so blessed. Though he had close collaborators early on in talented individuals like the German-born engineer Paul Mueller and Welsh stone mason David Timothy, as Wright's practice grew more unconventional – and his personal life more chaotic – such working friendships grew harder to find. In fact, Cleary makes a good case that Wright turned periodically to concocting systems for modular and prefabricated houses, such as American System and Textile block, not only to expand his reach as a designer, but to also try to circumvent the need for him to supervise the construction of his houses – projects that often threw a curve at contractors.

Another chapter on "Wright and Worshipping Communities" by Joseph M. Siry is equally well taken. As a young Turk, Wright hired on at Adler and Sullivan just as the firm was pushing the space-spanning envelope with the instantly famous Chicago Auditorium and, being from a clan of ministers, he was impressed. Wright returned time and again to the design of people-gathering buildings, and he produced a variety of auditoriums and theaters along with a succession of churches, starting with Unity Temple and including the remarkable Beth Shalom Synagogue of 1953-59. Taliesin West and III are arguably temples of enlightenment too, the latter with its own theater.

A recurring theme in all the essays is how Wright's unique take on residential architecture often was the wellspring for larger visions. In "Making Community out of the Grid" Neil Levine explores how Wright's innovative Prairie houses were not conceived in a vacuum but as key elements in a much larger suburban ensemble – yet another example of within-outward.

Perhaps most surprising – even eerie – for us today is the last essay, "Wright in Baghdad" by Mina Marefat that covers an astounding 1957 proposal of nearly 90 drawings the architect poured forth at the age of 91. Baghdad is now all-too-familiar a name and charged with the baggage of recent events, but half a century ago it was far-off and mysterious, known to most Americans only through fairly tales.

It was also a place the local government hoped to bring into the modern world. Wright, whose affinity for foreign cultures and clients stretched back to the 1920s, took readily to the exotic locale and culture, especially the opportunity to build a city anew out of whole cloth. What he had in mind, though, was no Bartlesville, OK, or Broadacre city.

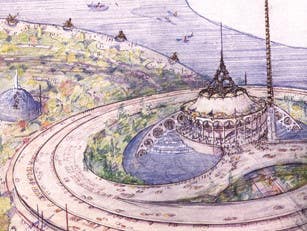

At first glance, the beautiful, colored-pencil renderings presented here look like Johnson's Wax meets Popular Mechanics, replete with futuristic cars winding up spiraled platforms and aircraft resembling toy tops spinning overhead. On closer reading, though, we learn that Wright's concept was actually a melding of ancient local architecture and culture with prescient green-building ideas – a mix that was way out in left field in the heyday of Modernist design.

In a plot twist not un-Wrightian, his vision may well have been right pew, wrong church, for now it is nearby Dubai that reaches for the fantastic future, down to constructing artificial islands and world's highest building. But that was Wright – ever outward, and still waiting for us to catch up to him.TB

Gordon Bock, longtime editor of Old-House Journal, is a writer, architectural historian, lecturer, and technical consultant who comments on historic buildings at www.bocktalk.com.