Profiles

FFKR Architects: Designing for the Spiritual

Religious buildings have been among the most inspired commissions of some illustrious architects – think H.H. Richardson, Cram and Goodhue, and even Frank Lloyd Wright – but, with exceptions, seldom the mainstay of the whole practice. What then brings a firm to work with a religious group when the bread-and-butter jobs are inevitably far more secular? Each case is different, but a stirring example is FFKR Architects of Salt Lake City, UT. With an office some 107 people strong, they've grown a client list that ranges from retail entrepreneurs to Native American tribes, to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and church projects that run from rehabilitating historic buildings to re-creating a long-gone temple.

Beat'em, Join'em

Such a diverse practice may seem like a reach, until you realize that the firm's origins are equally eclectic. The present-day FFKR dates from 1976 through an unlikely joining of forces. According to principal Roger P. Jackson, AIA, LEED AP, Robert A. Fowler Architects received the commission for the Salt Lake City Bicentennial Arts Center project through a rigorous interview process. After a congratulatory letter from Frank Ferguson, a former employee, Fowler invited Ferguson and his firm to collaborate on the project. They subsequently joined forces and became Fowler, Ferguson, Kingston and Ruben. In about 1984, the company was reorganized into FFKR Architects.

Jackson, who describes himself as part of the third wave of owners since FFKR's inception, says the firm engages in a broad base of architectural work, from school and university projects to retail. Principal Jeffrey L. Fisher, AIA, agrees. "There's a lot of commercial and retail, such as grocery stores and auto dealerships, and then a little bit of everything in between, including Native American gaming hotels and administration buildings."

Fisher himself has worked extensively with Native American groups, an auto dealership that has expanded into cinema, and several adaptive reuse projects, such as converting a former furniture warehouse into basketball practice courts. Says Fisher, "Often we have clients that ask us, "What can you do with this building to work with my current needs?'"

FFKR also does a lot with the state of Utah and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), where they have been busy almost continuously for 15 years at the campuses of Brigham Young University at Provo, UT, and Rexburg, ID.

Into the Fold

Even in Utah, how do you get from chain grocery stores and car dealerships to working with a religious client like the LDS? As Jackson explains, the relationship actually began with a commercial historic building project, the 1911 Hotel Utah in Salt Lake. Years back Robert A. Fowler Associated Architects had put an addition onto the grand old hotel, so as Fowler's successor, FFKR had had ongoing work in the building for years when the LDS Church bought it.

"I was the project architect for converting the Hotel Utah into a new church office building – my first big project – and as adaptive reuse it worked really well," says Jackson. The Utah Hotel, rechristened theJoseph Smith Memorial Building, now holds a 500-seat theater for church-related shows, as well a family history center (for genealogical research), but for FFKR it also became the stepping stone to another historic church property: the Vernal Utah Temple. Located about three hours east of Salt Lake City in Vernal, UT, the building was erected in 1908 as the Uintah Stake Tabernacle and for 90 years served as a meeting house, lecture hall and gathering place for the local membership. By the 21st century, however, the tabernacle had fallen into disrepair, so when the church decided to save the building by elevating it to the status of temple, the work meant not only gutting and renovating the structure but also bringing it up to modern seismic standards.

Since the Vernal temple was a solid, unreinforced brick building, four wythes of brick thick, FFKR's approach was to remove four inches of interior brick and replace it with a four-in. shell of reinforced concrete all around the insides of the building. Explains Jackson, "We would peel off the inner wythe and any loose pieces or chunks of brick, then bore into the remaining brick and epoxy-in bars. These bars are then tied into a reinforcing mat, over which we'd shoot on four inches of Gunnite concrete. That gives you the structural shell that you need to hold onto the outside brick in a seismic event."

This general method is one the firm has used on similar historic structures, such as the Noyes Building on the Snow College Campus in central Utah. In fact, seismic upgrades come into play on many existing-building projects at FFKR. According to principal Eric Thompson, AIA, "Utah is in a pretty high risk factor zone – just a little less than you have on the far West Coast – and all of our buildings have to meet strict structural seismic requirements." It goes without saying then that work on historic buildings, which tend to be unreinforced masonry, has a seismic side.

A good example of the process was the Salt Lake Tabernacle project (see Traditional Building, December 2009). Though well-built for 1867 and pre-railroad era Utah, when church leaders asked how the Tabernacle might fare in an event like the 1994 Northridge, CA, quake, simulation programs answered with a revelation: not good. As a result, in 2002 FFKR embarked on a two-year program of reinforcing the ring of 44 massive stone piers that support the structure and tying together the wood trusses that carry the roof.

And the threat is not unique to Utah either. At theLaie Hawaii Temple in Laie, Oahu, the two-year renovation begun in 2008 includes not only construction of a new rear entrance and front entrance canopy, restoration of ordinance rooms, and preservation of historic murals, but also a structural and seismic upgrade. Dedicated in 1919 as the first temple outside of the continental U.S., the structure is built of concrete made from crushed stone and coral.

Ecclesiastical Design

The firm also has commissions for new LDS temples, which raises an interesting architectural question: how best to design for a client that does not have centuries of architectural lineage going back to, say, medieval Gothic cathedrals or the ancient world of the Fertile Crescent? Explains Jackson, "Though it's nearly impossible to put into words, there's an image in the church of what a temple should be. A temple has to have the look and feel of a Mormon temple, which is quite soaring and swooping. It should be very vertical, to draw your eye up towards the heavens, but at the same time it needs to have a feel for the community in which it's built."

As an example, Jackson points to the Vernal Temple, which is adapted from an historic building typical of those built in the West in 1908. Time as well as place can influence design too. Recent temples are more traditional and "softer" than those of decades past, which tended to be angular and jagged. "Many of today's church leaders are interested in more traditional forms," says Jackson, "they want to abstract the design away from an institutional feel, yet they want the building to preserve the upward character, the searching, temple effect." He adds, "All the temples are different. I'm working on one in Philadelphia where we ask ourselves, 'What is it about Philadelphia that we can capture, and still make the building look like a Mormon temple?'"

While such a discussion may sound academic, it has very real implications for working on actual buildings – even "historic" ones. Take for example, the Nauvoo Temple in Nauvoo, IL, (see Traditional Building, May 2003). Says Jackson, "The Nauvoo Temple was an attempt to re-create an historic building, but with very little background information because that building is gone. Using just the few drawings and cryptic photos that we have left, we did everything we could to make it look and feel like it was built in 1846 – period furniture, period fabrics, period rug designs – but all the while hiding the technology of today."

Stepping back from the pulpit are projects that are re-dos of re-dos. Says Thompson, "Every so often we work on an historic building that had a terrible remodel just to get new occupants into the building. A lot of these buildings haven't been touched in 20 or 30 years, and now they're looking at a seismic retrofit as well." Such was the case with the Marsac Building in Park City, UT.

Built in the 1930s as an elementary school, the building was remodeled quickly in the 1980s when the municipal offices and police force took it over, and they had been living with the short-sighted results ever since. True to form, the most glaring evidence of post-oil-crisis-era changes was the lowered ceilings – acoustic tile that hid later forced-air ductwork but blocked 18 to 20 inches off the top of the windows. "We tore all that out and raised the ceilings back up at the window so there's the full 12-ft. window height again," says Thompson. "It lets in more light so now the interior space is a lot nicer."

Built with unreinforced masonry in a steel frame, the building needed much more than through-bolts to bring it up to modern seismic codes. As Thompson explains, "For each of the six new concrete shear walls, we ended up saw-cutting huge portions of the slab on the first level, and pouring new footings, about 3 ft. deep, by 12 ft. wide, by 30 ft. long." He adds, "When you get into a seismic retrofit, most of the time you're getting into the bones of the building and a whole new build-up, mechanicals included."

Overlooking all of old downtown Park City, the Marsac Building is not only an historic landmark but a model for the future. Park City is a genuine historic mining community, and very proud of its heritage. "Park City Municipal is really pushing all of the developers that are doing work in Park City to be more sustainable, and therefore Municipal is doing everything they can to lead by example," Thompson says.

To that end, the Marsac project incorporates state-of-the art technologies, such as ground-source heating systems. While the city did not go through the administrative process of applying for a LEED rating, "They asked us to do the calculations and show what a LEED rating would be" says Thompson, "and we designed to that."

Back to Church

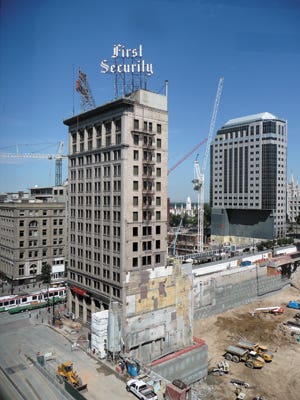

In downtown Salt Lake is another historic project that came close to a resurrection: the 1914 Deseret Building. "It's a classic early skyscraper," says Jackson, "14 stories tall with articulated lower floors with windows and public access (the base), stacked repeated floors (the shaft) and a fancy upper story with a cornice (the capital). It was built on a riveted steel frame with terra cotta on the outside." Trouble was, it sat in the middle of proposed mixed-use development owned by a for-profit arm of the LDS Church. Says Jackson, "One of the early plans was to raze the Deseret Building, but that put the whole city up in arms." The city council made a fuss, people wrote letters, and FFKR got involved to do the math on whether it made economic sense to keep and renovate the building. "We penciled it out," says Jackson, "and technically, no, it didn't make sense – but it was awfully close. So the developer said, 'Well, we can buy a lot of good will, and it's a great old building, so let's do it.'"

Here too FFKR's efforts included a seismic upgrade on the whole building. Says Jackson, "Though constructed with the best steel frame they knew at the time, the building is just built up with steel plates, angles, girders, and beams – not good enough for today. So much of what we're doing now is adding cross-bracing and stiffening, and reinforcing connections – shear elements so the building will withstand lateral forces." In the process, all the floors have been upgraded to class-A office space with a couple of tenants already moving back in – including the bank that long occupied the building. "It's a beautiful building," Jackson reflects, "and it has been a great project." And with results that, given the building's history, an entire city doubtless feels are divine.

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.