Features

Book Review: Beauty Memory Unity

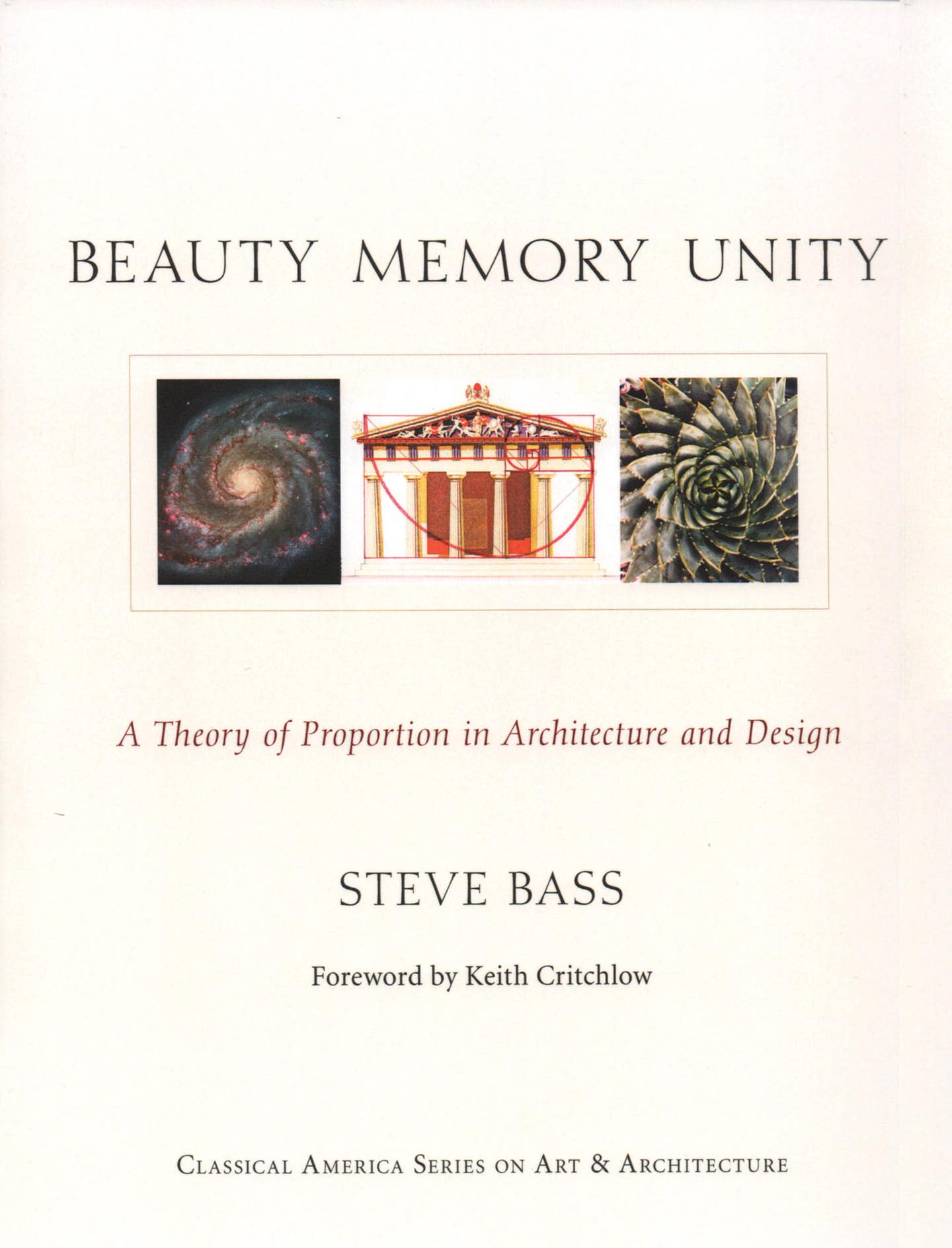

by Steve Bass

April 2019

Lindisfarne Books

First Edition

Paperback

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

In Beauty Memory Unity, architect, author, and sacred geometer Steve Bass invites us to accompany him upon a symbolic quest in search of beauty, an elevation of individual consciousness, a return to unity through remembrance.

What precipitates our journey is…love, the force that binds the cosmos together in harmonic arrangement and at an individual level the innate attraction that manifests itself initially as a desire drawing us toward the beautiful object. Our encounter with the beautiful awakens something within us akin to a memory so that we discover that the beautiful is in fact experienced, a state of being deeply ingrained within us.

An ancient model is presented where beauty emerges as a state of being in the psyche and consciousness which act as the nexus that conjoin ideas and sense, pattern and material. In this model number plays a vitalising role. Of particular interest is the use of number, not in counting or mathematical calculation, rather in its symbolic interpretation, notably geometry and harmony. One of the most fundamental interpretations of the numbers 1,2,3, & 4 relate to geometric concepts of singularity, extension, enclosure and materialisation symbolised by the point, line, triangle, and solid respectively. These same numbers are demonstrated in their most basic harmonic interpretation of the consonant tones of the tetrachord or lyre: the fundamental 1:1, the perfect 4th 4:3, the perfect 5th 3:2, and the octave 2:1. The harmonic progression of the tones of the lyre served as an analogy of the departure (fundamental) from and return (octave) to unity through number.

Of course, the aforementioned only serves as an initiation into symbolic interpretations of number. The author continues to expand upon this foundation, first with several geometric and harmonic diagrams, progressing to over 20 step by step examples of how these principles can be applied architecturally to the design of facades, plans, and architectural elements with the simple tools of ruler and compass. One can simultaneously experience and observe how designs can ‘grow’ from number like the unfolding of a flower.

A Theory of Proportion in Architecture and Design

Just as a few consonant notes can produce an infinite range of musical compositions that resonate within us, so too can the mastery of basic geometric and harmonic principles be utilised for a grand variety of architectural compositions in a similar manner. A key to unlocking the power of symbolic number is the Roman concept of ‘proportion’, known as ‘analogia’ by the Greeks; a concept of holistic unity in the entire work that one had to search no further than the human body to discover. About a third of the way into the reading we encounter an historical review of Classical architecture from Ancient Egypt concluding with a few examples of Federal architecture in the United States. The same geometric and harmonic principles previously demonstrated are now applied in the analyses and reconstructions of these historical examples. This is where the theory of proportion enters in. Rather than assert that these analyses were how these buildings were designed, the strong independent case is presented that such principles, being both generative and intuitive, accord with how these building might have been designed.

As previously, we are guided through many of the reconstructions step by step, invited to pick up compass and rule and experience proportion in deign viscerally. Where there is archaeological evidence or surviving written documentation in support of the use of geometric and harmonic proportional systems of design, it is presented. Such documentation increases exponentially in the Medieval and Islamic periods, with the use of geometric and harmonic proportion as a means of seeking unity through the pursuit of beauty became openly and self-consciously acknowledged during the Italian Renaissance where as Steve phrases it, they began “using attunement to physical beauty as a trigger for the elevation of consciousness.”

The Flight from Beauty and the Path of Return

Obviously, this is not the built environment we inhabit today. What happened? The latter portion of the book points to the late 17th century as having propagated philosophical ideas that challenged the understanding of beauty as an inherent aspect of nature underlying the unity of the cosmos, reducing it to a mere subjective, culturally determined epiphenomenon. The architectural interpretation of such a perspective diminished beauty from being an eternal search and source of inspiration to mere fashion and whimsy. Shortly thereafter there arises a replacement aesthetic of the sublime, pain based sensory experiences.

Stripped bare of the geometric and harmonic traditions underlying the generative vitality of traditional architecture, this so-called Enlightenment period presides over a rational reduction of architectural design to academic references and the application of historical precedents, initially maintaining the external form of a living culture but quickly desiccating internally. This weakened state of tradition opened the door for the ascendency of Modernism as an anti-Classical, anti-traditional movement that would fully align contemporary architectural practise, expression, and form with the Modern philosophy.

In conclusion, our author does not leave us without hope. He challenges that the anxiety, chaos, and grim ugliness of architecture are not inevitable. He invites us to an examination of 5,000 years of beautiful architecture and perhaps more importantly, points us towards the “logos”, the generative principles that led to their creation. The strong case is made that the path to unity through beauty remains with us, more accurately within us and only awaits inducement to remembrance.

My name is Patrick Webb, I’m a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of natural, historically utilized plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime in contemporary architectural specification.

I was raised by a father in an Arts & Crafts tradition. Patrick Sr. learned the “decorative” arts of painting, plastering and wall covering as a young man in England. Raising me equated to teaching through working. All of life’s important lessons were considered ones that could be learned from the mediums of tradition and craft. I found myself most drawn to plastering as I considered it the richest of the three aforementioned trades for artistic expression.

This strong paternal influence was tempered by my grandmother, Geraldine Webb, a cultured, traveled, well-educated woman, fluent in several languages. She made a point of instructing her young grandson in Spanish, French, formal etiquette and opened up an entire worldview of history and culture.

After three years attending the University of Texas’ civil engineering program with a focus on mineral compositions, I departed, taking a vow of poverty, living as a religious aesthetic for a period of seven years. This time was devoted to clear reasoning, linguistic studies, examination of world religions, exploration of ethics and aesthetics. It acted as a circuitous path leading back to traditional craft, now imbued with a deeper understanding of interconnection in time and place. I ceased to see craft as simply work or labor for daily bread but among the sacred outward expressions of the divine anifest

within us.

From that time going forward there have been numerous interesting experiences. Among them study of plastering traditions under true masters here in the US as well as in England, Germany, France, Italy and Morocco. Projects have included such high expressions of plasterwork as mouldings, ornament, buon fresco, stuc pierre, sgraffito and tadelakt.

I’ve been privileged to teach for the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, where I currently reside and for the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art across the US. “Sharing is caring” – such a corny cliché but so true. I hardly know a

thing that hasn’t been practically served to me on a platter. I’m grateful first of all, but now that I might actually know a few things, it becomes my responsibility to be generous as well.