Restoration & Renovation

The Restoration of Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library’s Ceiling

Conservator John Canning & Co.

Fine-Arts Conservator Gianfranco Pocobene Studios

With its 60-foot ceiling, cloisters, 3,000 clerestory-style stained-glass windows, side chapels, and altar-like circulation desk, Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library stands as a visual testament to the cathedral of knowledge—and to the work of architect James Gamble Rogers.

Completed in 1930, the ornately ornamented library, the university’s largest and sited in the heart of the Central Campus, was part of the 1924 master plan devised by architect Rogers, Class of 1889, and is one of 19 buildings he designed and erected over that next decade that would establish Yale’s Collegiate Gothic architectural identity.

Named for its benefactor, New York City lawyer and 1864 alumnus John William Sterling, the iconic towered library, whose layout is in the cruciform style, houses more than 2.5 million books on 16 floors of stacks.

Over the last 40 years, architectural conservator and restoration contractor John Canning & Co. of Cheshire, Connecticut, has been commissioned not only to do a variety of restoration and replication work on the library but also on a number of Rogers’ other historic buildings on the university’s New Haven, Connecticut campus.

For the latest commission, John Canning & Co. restored and conserved the Sterling Memorial Library’s ceiling, woodwork, and the its Alma Mater mural.

“I’ve worked on most of Rogers’ buildings at Yale,” says John Canning, one of the principals of the firm that he established in 1978. “In order to properly conserve or restore decorative finishes and artwork, one must understand the original materials and method of execution prior to commencing the work.”

In this case, that meant drawing upon his vast knowledge of the techniques employed by Rogers, who, inspired by the century’s old buildings of Oxford and Cambridge universities, wanted his structures to look as though they had stood for hundreds of years.

“Rogers did things like put cracks in windows and repaired them using mismatched stained glass and 15th-century techniques to draw attention to their artificial age,” Canning says. “He also ground down stair treads to make them look as though they were worn down by generations of use, and his painted decoration effects begin with his treatment for textured plaster substrate so they look like they are set in old plaster. In this time, he was roundly criticized by his peers for being too theatrical. They had a lack of understanding of what he was trying to do.”

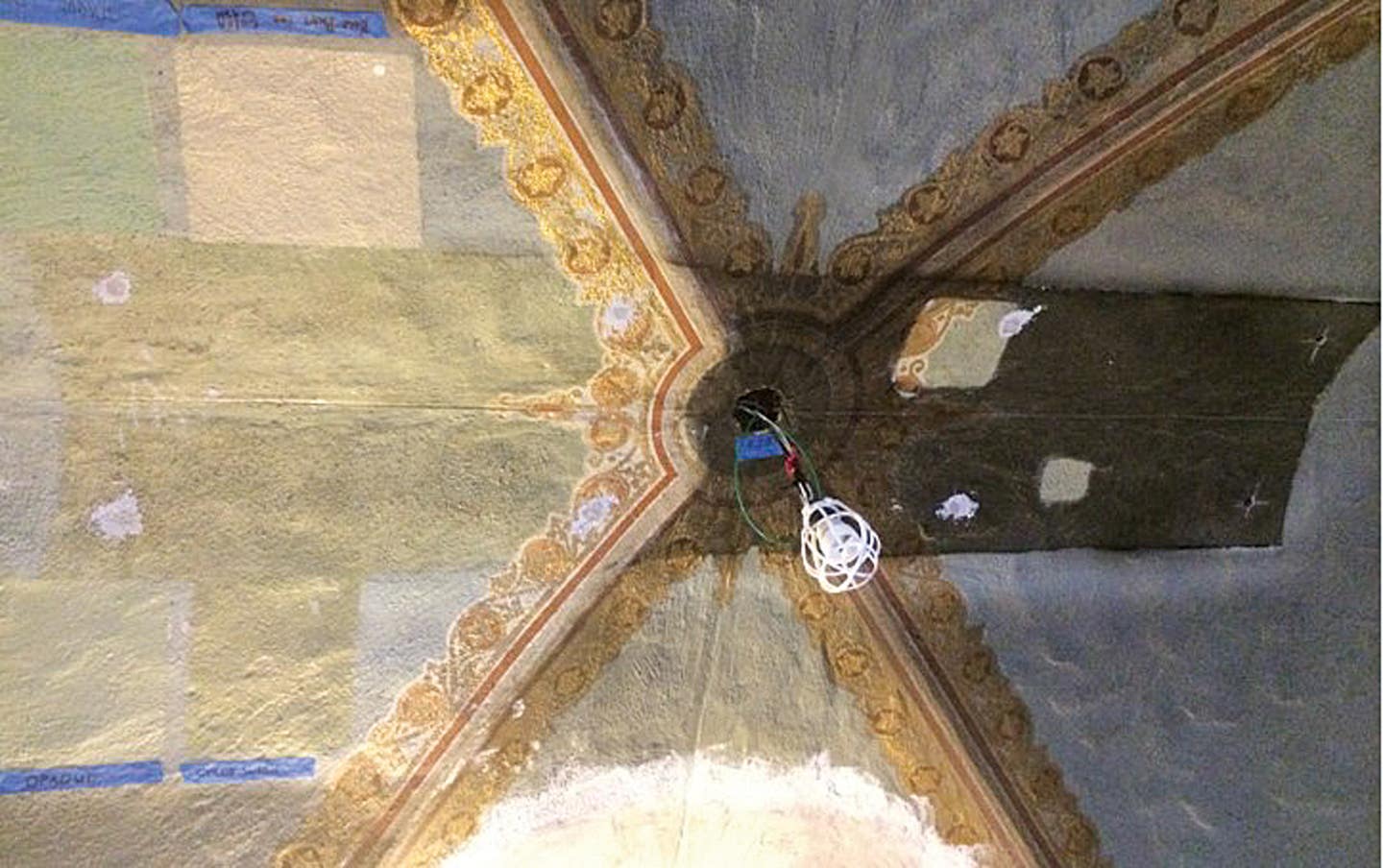

The Canning team developed a custom aqueous solution to clean the textured and decoratively painted plaster ceiling and bas-relief ornament, including gilded crosses with bars.

“This was a challenge because we had to find a way to uniformly clean everything, including the crevices, which in some cases were half an inch or more deep,” Canning says. “Rogers’ technique not only added age but drama, movement, and interest.”

Canning’s team applied a neutral pH solution in a gel form or a poultice, allowing it to dwell for 15 minutes to draw everything to the surface, which was then carefully cleared with water.

“We did the same thing when we were called in to help restore the Sky Mural in New York City’s Grand Central Station,” Canning says.

Re-creating the original color scheme at the north aisle ceilings was not as straightforward as following a single paint sample, which revealed only one hue.

“Every finish that Rogers used was a multi-colored wash of oil paints,” Canning says. “Coupled with the textured plaster, this gave the effect of aged tempera paint. When the eye puts them together, it creates a color with a feeling of great movement. Generally, he used two to five colors, especially on walls, and scumbled or blended them in an irregular fashion.”

With the removal of a six-foot-long 1950s fluorescent lighting fixture in the groined vault ceiling, an encapsulated area of the original finishes was revealed. The heterogenous effect intended by Rogers was created with the combined irregularities of multicolored washes and textured and relief plaster. Once studied, the design was replicated in the same fashion.

The library’s woodwork, parts of which had water damage, was conserved and restored to an earlier finish, however, not to the same specifications of Rogers’ original design.

Rogers’ original specifications for the woodwork throughout the library described quartered white oak panels that were hand planed to show plane marks then treated with caustic soda, which Canning says, naturally accelerates the aging process. Rottenstone, which is essentially limestone, was applied to achieve a chalky look. After the wood was shellacked, unbuffed beeswax was rubbed on as a protective coating.

The finish, Canning adds, was not meant to be shiny. “The original furniture of the library was finished in the same way,” he adds.

The library’s Alma Mater mural, by Eugene Savage, was conserved and cleaned under the direction of Gianfranco Pocobene, whose eponymous studio is in Malden, Massachusetts.

The mural, set in the back wall, features allegorical figures representing her academic schools.

“I love seeing how the library would have looked originally,” Canning says. “You can see all the colors, techniques and decorations. On a very bright day, it looks brilliant under natural light. Everyone thinks it is because of the new lighting systems, and that does help, but it’s really all because we replicated Rogers’ techniques.”

Working at Sterling Memorial Library again was “kind of like being a kid in a candy factory,” Canning adds. “I’m delighted that I got the chance to pay homage to James Gamble Rogers’ original intention.”