Restoration & Renovation

Adaptive Reuse Spurs Urban Renewal

Project: Stony Island State Savings Bank, Chicago, IL

Designer/Project Manager: Place Lab, Chicago, IL; Mejay Gula, designer/project manager

Architect of Record: FitzGerald Associates Architects, Chicago, IL

Historic Consultant: MacRostie Historic Advisors, Chicago, IL

In the typical restoration project, a developer buys a crumbling icon to save it from the thunderous wrecking ball. Architects, interior designers and a variety of craftspeople and contractors spend years–and tons of money–returning it to its original glory so it can be put to a brand-new repurposed use in a chic neighborhood.

That’s not what happened on the South Side of Chicago. If you have not heard, in this new age of Uber and crowdfunding, a grass-roots group in the Windy City pulled off an astounding DIY urban renewal project that, in scale and approach, is unique among the area’s other adaptive-reuse projects and serves as a model for the future of urban renewal.

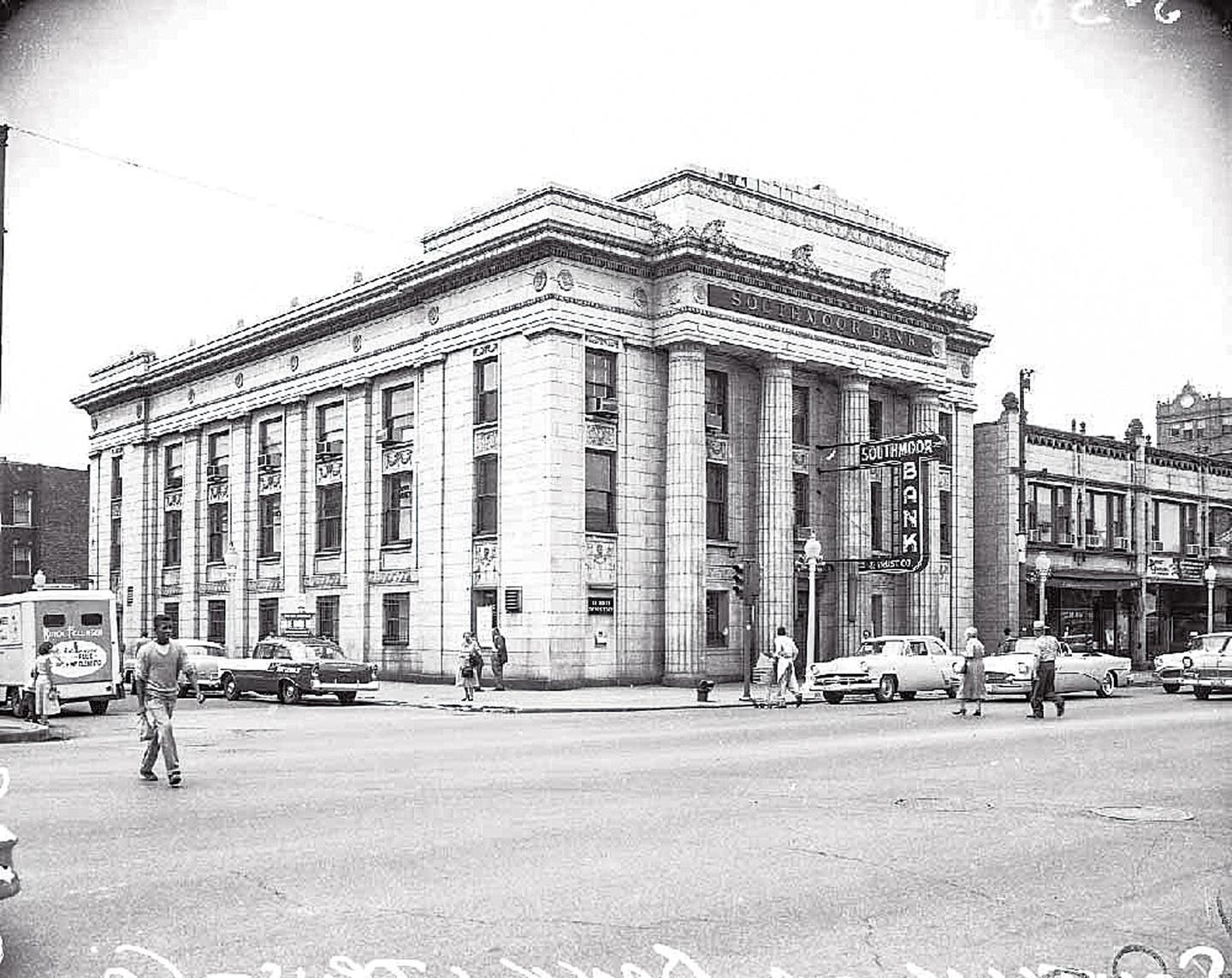

The story starts at East 68th Street and South Stony Island Avenue, nine miles south of the Loop, where the Stony Island State Savings Bank stood sentinel just south of Jackson Park for decades as the vibrant commercial corridor it anchored fell into deep decay. The 26,000-sq.ft. Neoclassical bank building, designed by William Gibbons Uffendell, opened its doors in the then-prosperous area between the Greater Grand Crossing and South Shore neighborhoods in 1923.

It served its function for some 60 years before it was abandoned in the early-1980s. Time–and water and snow that fell through holes in the roof – took its toll, and after changing ownership several times, the building became city property in 2011.

Everyone wanted to preserve it, but although several developers expressed interest, nobody came up with a viable plan for the structure that would revive it as well as the area. The standstill ended when another South Side building collapsed and killed a pedestrian, prompting the city to review the physical state of its properties. The bank was red flagged, and demolition crews were set to move in in 2012 when a blogger, Eric Rogers, took note of the pending proceedings.

The bleak post caught the eye of artist/scholar/urban planner Theaster Gates, the creator of the Rebuild Foundation, a non-profit that focuses on cultural driven redevelopment and affordable-space initiatives in under-resourced South Side communities. Gates, a University of Chicago professor whose art has been exhibited at the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Whitney Biennial, was long familiar with the Stony Island State Savings Bank as he had developed a conclave of concept projects —the Black Cinema House, the Archive House, the Listening House, the Black Artists Retreat, and with a developer partner, the Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative—in that area.

In his native city, Gates is perhaps best known for the proposed installation he designed in 2014 for the South Side’s 95th Street subway station, the largest public art project in the Chicago Transit Authority’s history.

His team took a tour of the bank and instantly made a proposal for its rehabilitation and reactivation. He created a new LLC–Stony Group–and sought a capital investment loan from Chicago Community Loan Fund to pay for the proposed renovation project and negotiate the sale from the city in 2013. And that’s virtually the last conventional thing Gates and his team did.

Instead of tapping venture capitalists, he took a creative approach to fund-raising, selling 100 “Bank Bonds” for $5,000 each. Inscribed “In ART We Trust,” they were made from marble slabs from the building’s bathrooms. He also sold $50,000 “bonds.” In addition, Rebuild raised more than $1.1 million by selling tickets to a gala to finance the bank’s cultural programs. The project was awarded $1.1 million in tax credits from the Illinois State Historic Preservation Office, and Stony Group took out a conventional $6.2-million loan.

From conception, Gates treated the building as a work of art, not an architectural restoration. “We never had any intention of making it look like it did in 1923,” says Mejay Gula, building strategist and construction manager for Place Lab, Gates’ Knight Foundation-funded ethical development organization. “It would have been far too expensive. Gates has an aesthetic to sculpt spaces, and as an artist, he saw the value in displaying this history. This community has experienced disinvestment for decades, and the symptom of deterioration is part of that narrative.”

The first priority mandated by the city was stabilizing the terra-cotta façade, which has a faux granite finish, and securing the bank from the elements, which required replacing the skylights and windows and pumping out the water inside.

“As soon as we did this, a young man threw rocks and broke three windows,” she says. “This was in the beginning when only contractors were there and before anyone from Rebuild was on the site. It was disheartening, so we talked to businesses and their patrons and found out that the rock thrower’s actions were prompted by the misperception that this project was just another white developer taking another building of ours.”

Once he–and the others in the area–understood that an African-American artist and neighbor was behind the project and planned free cultural programs for the community, the vandalism stopped and the hope began. Although the state required the restoration of key parts of the bank’s architecture, including the replication and replacement of wood trims, it went along with many of Gates’ ideas. The woodwork and metalwork was done by the Theaster Gates Studios.

“We, for instance, were not required to replicate the elaborate ceiling plaster,” Gula says, “which was fine because our idea on most everything was to keep what survived and patch what didn’t. It was the same with the paint. We were not required to repaint, which allowed us to keep the dilapidated, peeling look. All we had to do was scrape and cover what was existing with a clear sealer.”

The biggest challenge, she says, was getting everyone from the architect of record to the restoration consultant to remain flexible. “Because this is an artwork, you have to wait until things inform you whether to turn left or right,” she says. “There was a lot of indeterminacy. For example, we initially planned for a commercial kitchen and restaurant but decided against it. For architects and general contractors used to following a certain plan, this was hard to accept.”

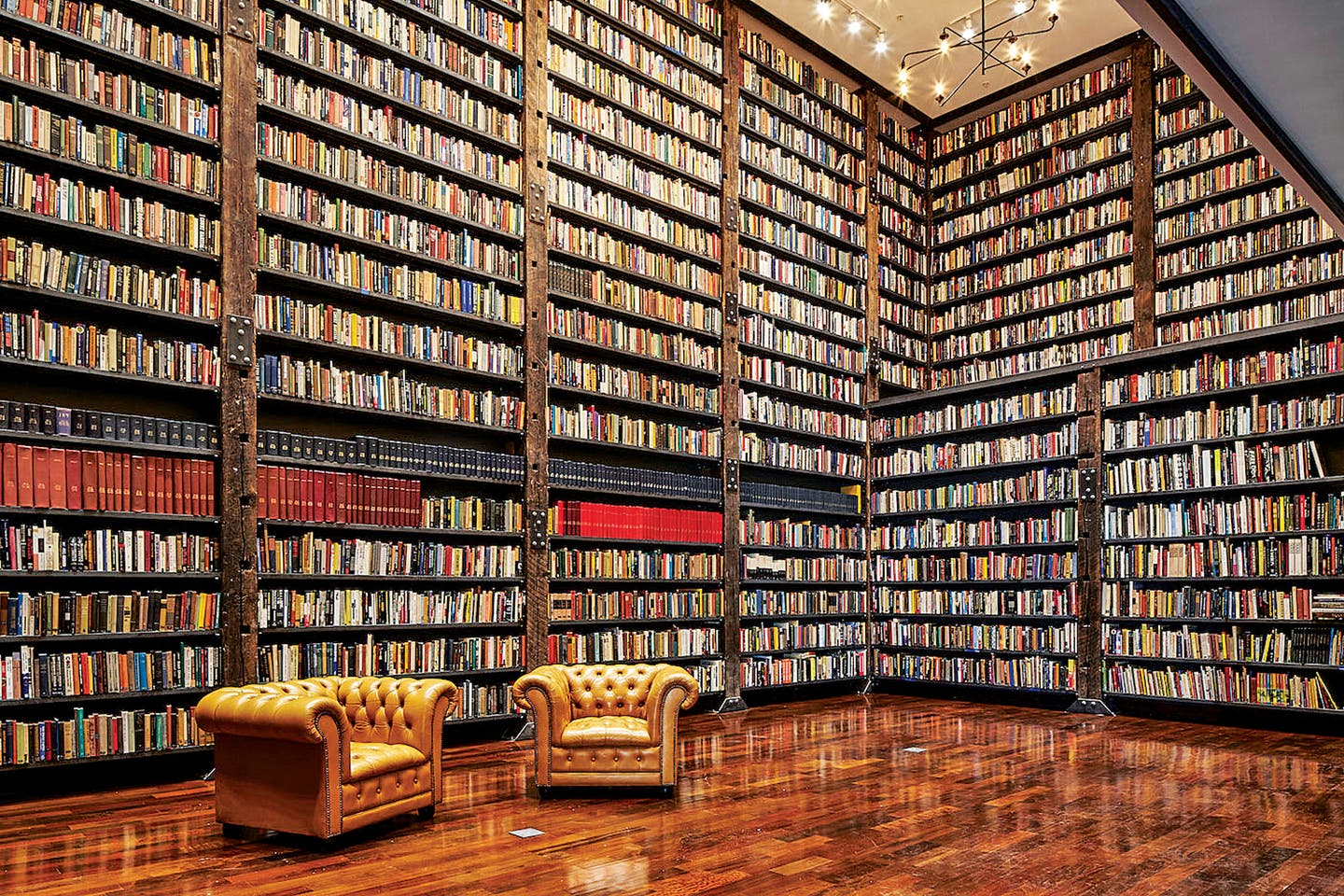

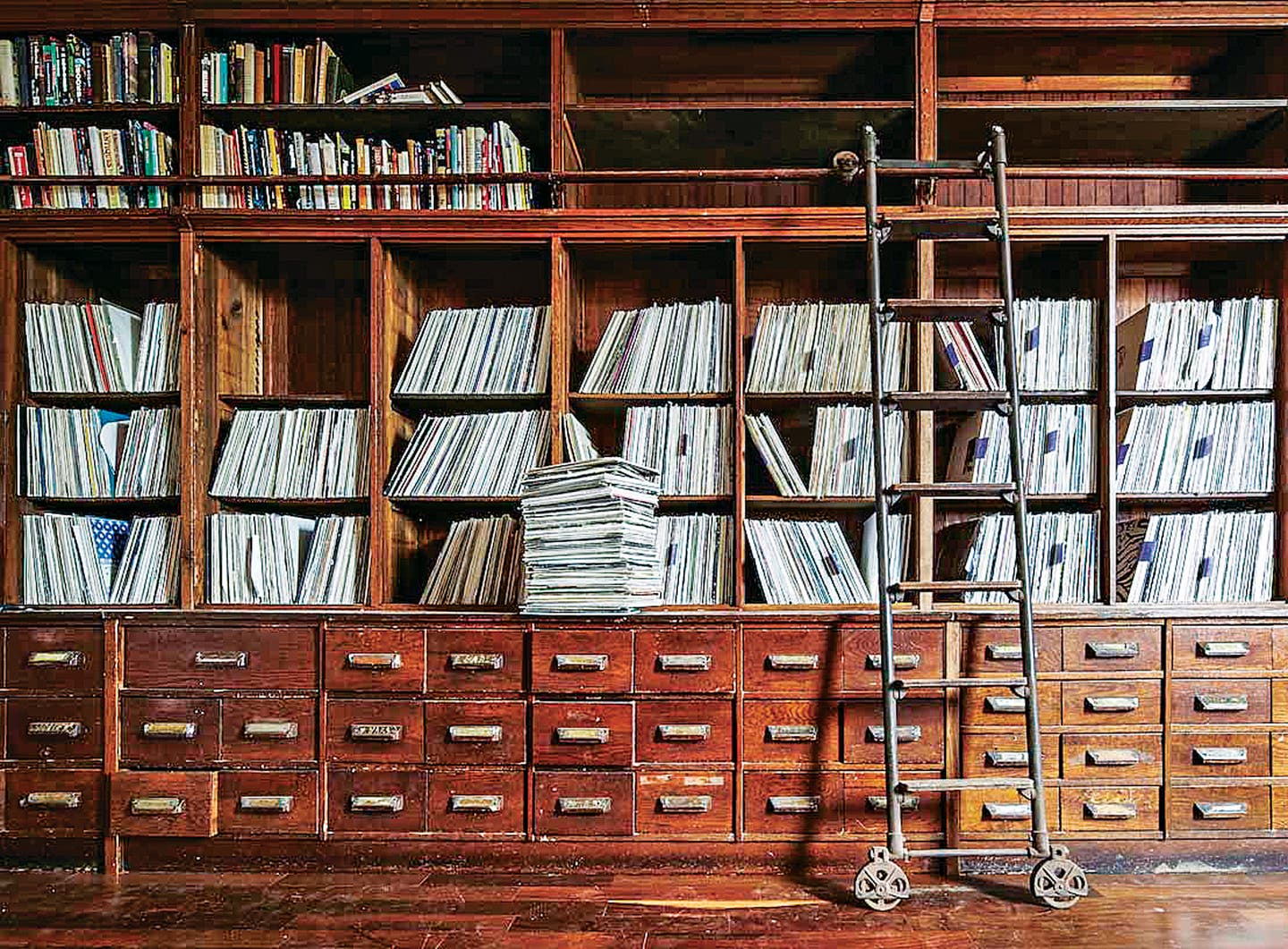

In the end, though, each of the floors was given a dedicated use. The soaring first floor has been reserved as an artist exhibition space; the second floor houses the Johnson Publishing Archive + Collection and more than 60,000 glass lantern slides of art and architectural history from the collection of the University of Chicago; and the third floor features the 4,000-piece “Negrobilia” collection of Edward J. Williams and the extensive vinyl collection of Frankie Knuckles Records, a shuttered Chicago shop.

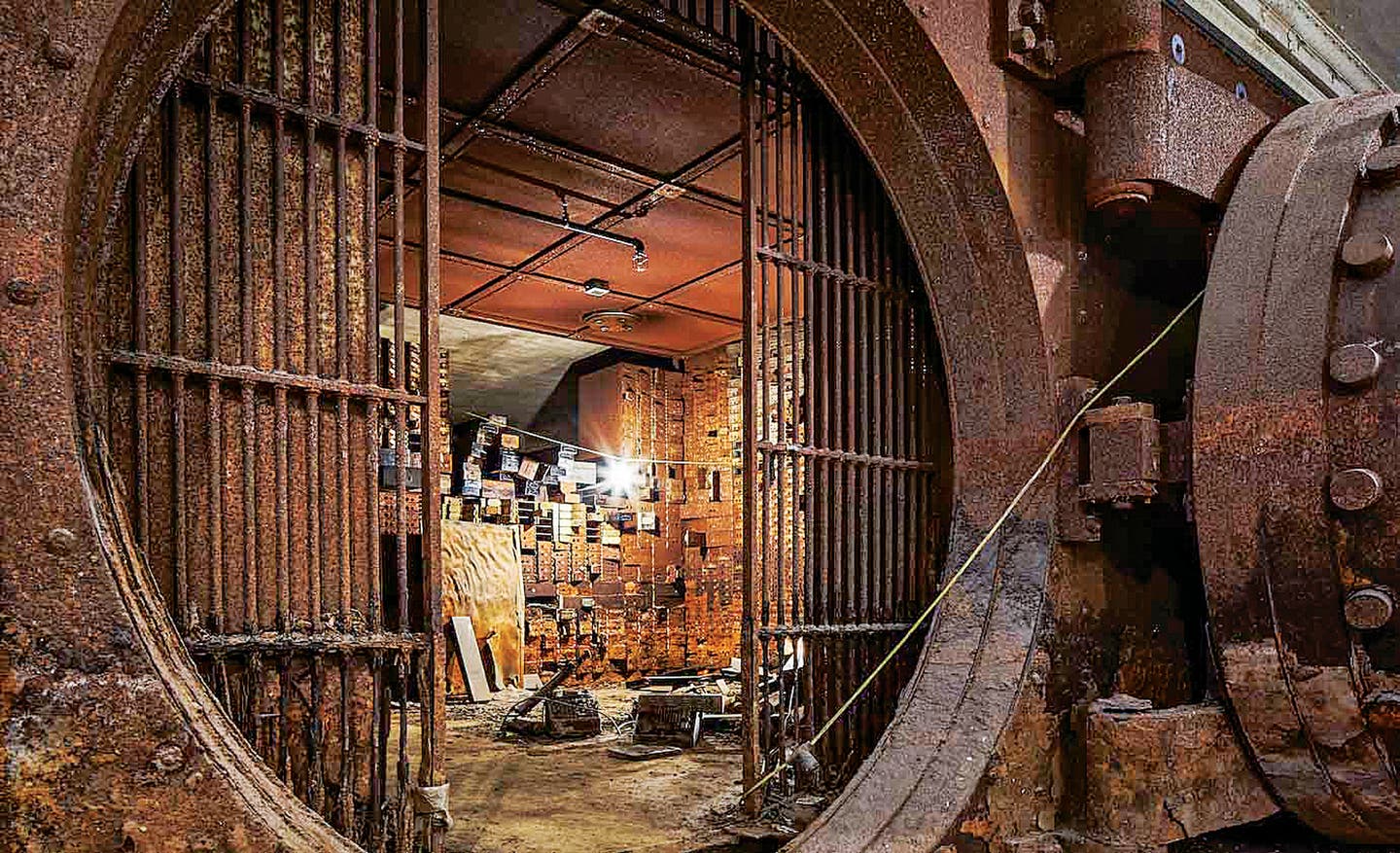

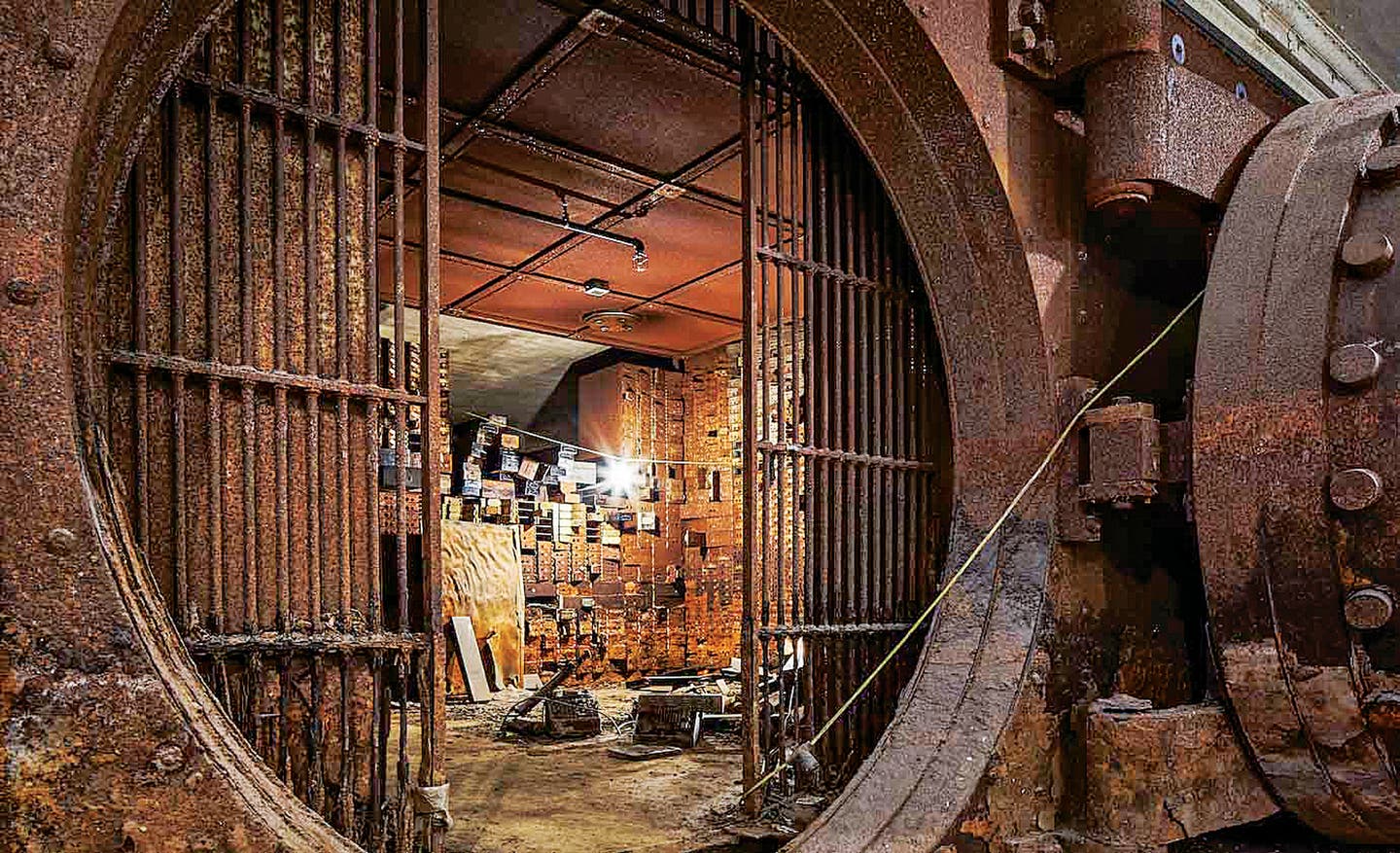

The basement, where the monstrous red-rusted vault resides, has been left much as it was. “We’re giving limited tours of the vault,” Gula says, “but currently this floor is un-programmed. We do know that we are not going to change anything about it.”

Gates is known for using found architectural objects in his art, and when new construction was warranted, Gates’ team, whose 60 members include a carpenter, a metal fabricator and a ceramic artist, designed and built in a period-appropriate manner using salvaged materials.

The floor-to-ceiling bookcases for the Knuckles collection, for instance, are from a vintage hardware store in Chicago, and the bookcases in the Johnson Library were fabricated from reclaimed beams punctuated with new old-style metal plates. And in the reading room, the tables were fashioned from rooftop water tanks.

The newly named Stony Island Arts Bank reopened in October 2015, the first day of the city’s premiere architectural biennial. Its soaring atrium featured the floor-to-ceiling cardboard columns of Portuguese artist Carlos Bunga. Titled “Under the Skin,” the work was meant to engage not only with the architecture of the building but also with the fabric of the African-American community.

Gates, who has been quoted as saying that his projects require belief more than funding, has put an enormous amount of faith into the bank, calling it “a repository for African-American culture and history, a laboratory for the next generation of black artists, a space for neighborhood residents to preserve, access, re-imagine and share their heritage, as well as a destination for artists, scholars, curators and collectors to research and engage in South Side history.”

Gula acknowledges that the re-purposing of the bank doesn’t mean that the rest of the corridor will follow suit. The building is, in essence, still a loner. There are limited attractions or even amenities like restaurants on that street to encourage visitors to come. “Rebuild Foundation has a network of other buildings that offer diverse cultural programming, and they are beautiful in and of themselves,” Gula says. “People could spend a whole day visiting all of these spaces.”

She’s convinced, though, that in time–and it may be a long time–other businesses will begin to see opportunity in investing here and those that already exist will see opportunity in staying.

“The project will be economically generating for us in the long term,” she says. “We are of the philosophy that if you add a cup of water to the well pump, it yields more water.”

And part of that cup, she hopes, will be filled by the people who live around and use the Stony Island Arts Bank. “We’re still trying to find ways to open doors wider to the community,” Gula says. Recently, the Stony Group landscaped the eight empty blocks that lie to the north of the bank so it can offer outdoor programming and host events.

Gula says the Stony Island Arts Bank will always be a work in progress. “The building was a visual anchor even in its vacancy.” she says. “For decades, it stood to represent disinvestment, and now we hope it grows to represent cultural vitality for the community. It means a lot to save it.”