Public Buildings

Old City Hall in Washington, D.C. Gets A Modernist Pavillion

Project: Old City Hall in Washington, DC

Architect:Beyer Blinder Belle, Washington, DC; Hany Hassan, partner

By Kim A. O’Connell

“We wanted to create something of its time, or maybe timeless, that was very subtle and would not compete with the existing building,” Hassan says. “It had to have its own place and simplicity and beauty."

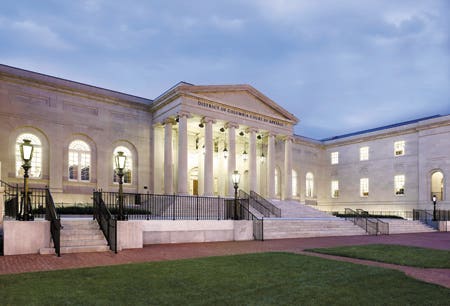

In the annals of American jurisprudence, few buildings are as historic – and as overlooked – as Washington, DC’s historic courthouse, a well-proportioned Classical structure anchoring the southern end of the city’s Judiciary Square. The building has always paled in comparison to all the other, better known Classical buildings in the nation’s capital, and especially to the mammoth red-brick National Building Museum that sits on the square’s opposite side. That impression may now change, however, thanks to a Modernist steel-and-glass atrium that serves as the building’s new entrance.

Designed in 1820 by George Hadfield, who worked on the U.S. Capitol and designed Robert E. Lee’s stately house in nearby Arlington, the courthouse served as the District of Columbia’s original City Hall. A designated national historic landmark, the building is characterized by Classical, symmetrical massing, arched windows and an Ionic south-facing portico. Many notable events have occurred there in the last two centuries, including the trials of Texas statesman Sam Houston and Lincoln co-conspirator John Surratt. Daniel Day Webster and Francis Scott Key practiced law in the building, and Frederick Douglass kept an office there too. Over the years, it became the centerpiece of a large legal complex comprising several other federal and city court buildings around the square. Despite its historic status, however, the building had deteriorated over the years and was vacant by 1999.

Today, more than a decade later, the building has been completely restored and reopened as the DC Court of Appeals, the district’s highest court. Led by the New York-based preservation and design firm Beyer Blinder Belle (BBB), whose DC office was awarded the work under the auspices of the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence program, the project included a complete restoration of the historic building, the inclusion of new programmatic spaces and, perhaps most notably (and controversially), the addition of the Modernist glass atrium. The addition now serves as an entrance pavilion to the building and is reached by a new accessible plaza.

BBB worked with civil engineers Wiles Mensch Corp. of Reston, VA, structural engineers Robert Silman Associates of New York, general contractors Hensel Phelps Construction Co. of Greeley, CO, and construction managers Clarron Consulting of Dulles, VA, on the project. Mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineers Joseph R. Loring & Associates of New York were also involved.

A Classical Landmark

Although the courthouse has gone through several renovations since its inception, the most dramatic changes occurred in 1917, when Elliott Woods (then Architect of the Capitol) was commissioned to upgrade the building. In addition to completely re-cladding the original stucco exterior in limestone and changing the fenestration, Woods removed the shallow portico that once stood on the building’s north side, effectively divorcing the building from its intended connection to the square. Placing the new atrium on the north side, according to the firm, reverses Woods’ decision and reorients the building once again to Judiciary Square.

“We looked at the building from the perspective of its status as a landmark, but also how it relates to the fabric of the city around it,” says Hany Hassan, partner and director of the firm’s DC office. “It was built as a single building, but now it plays that role as the heart of a whole assembly of courthouses, so we wanted to connect the building to the rest of the campus and make it accessible.” Yet the atrium is far from a replication of the original portico. Essentially a steel-and-glass box, the pavilion has more in common with the iconic works of Philip Johnson and Mies van der Rohe (such as the Mies-designed Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial Library only a few blocks away) than it does with the courthouse’s traditional precedents.

In his positive review in The Washington Post, critic Philip Kennicott praised the “sexy glass box” as being “elegant, never out of fashion and appropriate almost anywhere.” Hassan says that it was important that visitors were able to see the original structure through the glass, but adds that the firm took care to counter that transparency with six front-facing steel columns, which are a Modernist nod to the former portico’s traditional columns.

“We wanted to create something of its time, or maybe timeless, that was very subtle and would not compete with the existing building,” Hassan says. “It had to have its own place and simplicity and beauty. At the same time, one could have simply built a clear, transparent box, and you need to see the proportion of the addition. That’s why the introduction of the columns gave it more presence. It needed that – you would have been going from a masonry building to a completely transparent addition.”

A Modernist Addition?

Some traditionalists may take issue with the firm’s insistence on designing an addition that differs so strongly from the original. “All too often a Modernist addition to a Classical landmark building is a missed opportunity to make an addition that is neither a copy of the historic structure nor an alien intrusion, but a distinguished new neighbor,” says Steven W. Semes, author of The Future of the Past: A Conservation Ethic for Architecture, Urbanism, and Historic Preservation. “To accomplish that requires the architect to approach the historic structure with knowledge and respect for the formal language and building culture that produced it, rather than imposing an alien and dissonant view on the landmark.”

Hassan asserts that he has profound knowledge and respect for the building and the traditions that produced it. “We did an unbelievable amount of research,” he says. “This building is coming into a new life, and the building has changed in terms of its context. We have to understand and respect that from an urban design standpoint, and we have to merge that into a solution that does not necessarily become a simplification of the original portico that was once there. If you were to begin to mimic that or simplify that, it would have been practically forced.”

As evidence of the care he took to preserve the historic building, Hassan points to the painstaking effort to design and build a new ceremonial courtroom space beneath the south portico. This part of the project included new reception and exhibit space and administrative facilities as well, which allowed as much of the historic façade and above-grade building fabric to be retained as possible.

To accomplish this, the original stone and brick support structure was removed in its entirety, while keeping the portico in place, and replaced with a new steel structural framework – a process that took nine months. This also allowed new mechanical equipment to be placed in the residual space between the existing foundation wall and a new, underground parking garage, further protecting historic areas above. For the interior, the firm restored original marble and terrazzo flooring, wainscoting, plaster moldings, laylights and light fixtures. Lighting was done by Domingo Gonzales Associates of New York City.

Dropped ceilings were removed to reveal the historic plaster ceilings, and new finishes were designed to complement the historic detailing. Outside, a new landscape scheme designed by Rhodeside & Harwell of Alexandria, VA includes grass, trees, plants and fountains, as well as pervious paving surfaces and underground detention tanks that collect and temporarily store rainwater. An 1868 statue of Abraham Lincoln that stands in front of the south portico has been refurbished as well.

The firm is now engaged in the design of a courts museum that would be located in the new excavated space near the ceremonial courtroom. “This building has a lot of history,” Hassan says. “It’s an amazing icon, and the history of Washington, DC, is very much interconnected with this building. Completing this new design is another major responsibility. It’s just been a wonderful experience.” TB