Restoration & Renovation

The South’s Oldest Art Museum Building

PROJECT: Renovation of the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, SC

ARCHITECT: Evans & Schmidt Architects, Charleston, SC; Joseph D. Schmidt, AIA, owner and project architect; Richard A. Fisher, associate project architect

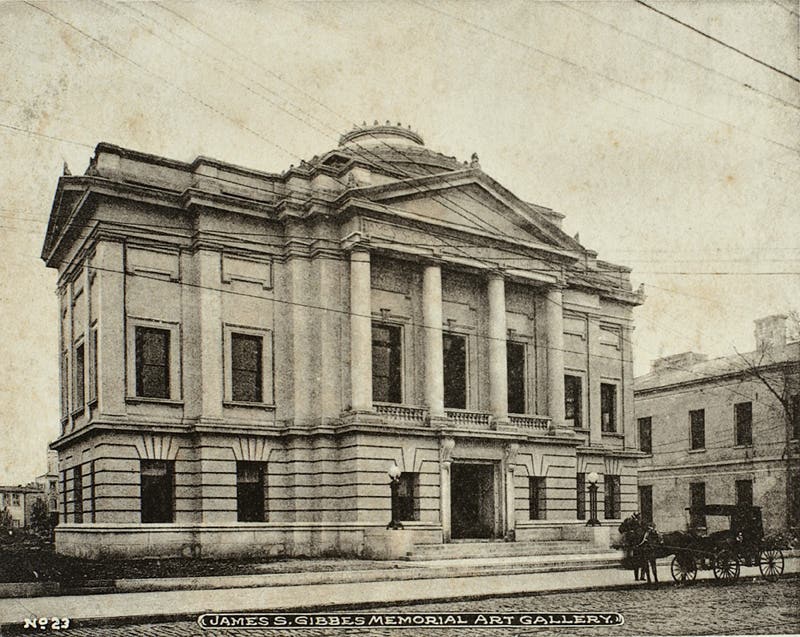

The Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, SC, has just written a new chapter in its long and illustrious history. The 111-year-old Beaux Arts building has completed a $14-million, two-year renovation and is ready to serve the community for another 100 years.

It all started in 1858 when James Shoolbred Gibbes left funds to the city of Charleston “for the erection or purchase of a suitable building to be used as a Hall or Halls for the exhibition of paintings and for necessary rooms for students in the fine arts…” The 12,500-sq.ft. two-story, Beaux Arts building designed by Frank P. Milburn opened to the public on April 11, 1905. Today the City co-owns the Gibbes with the Carolina Art Association, which is one of the oldest arts organizations in the country, founded in 1858.

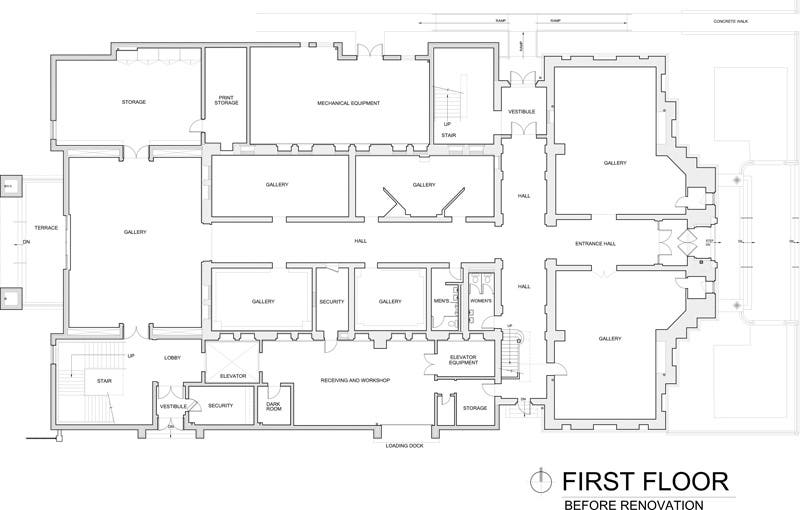

A $1.2-million renovation and expansion in 1977 increased the total square footage to 29,500-sq.ft. This was achieved by adding a wraparound addition that covered most of the building, and adding a third floor, leaving the two-story front façade and front section intact.

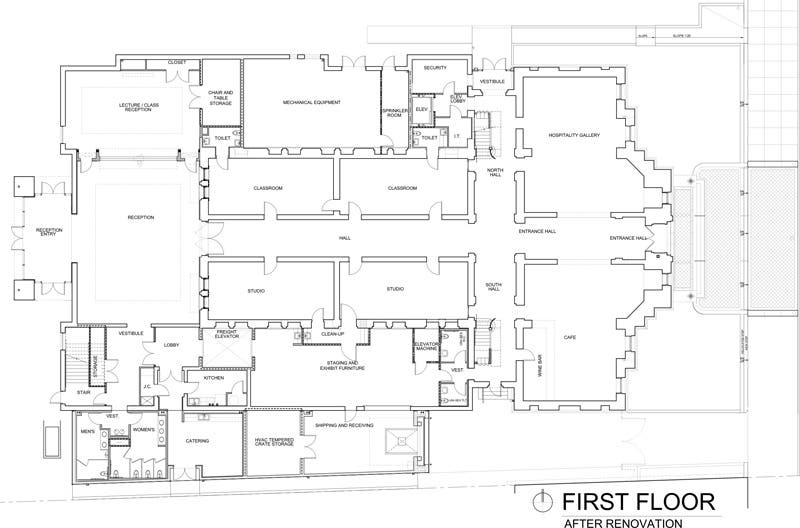

The just completed renovation led by Evans & Schmidt Architects of Charleston added more space, bringing the total to just under 42,000-sq.ft. It also restored many of the historic elements, reconfigured the exhibit spaces, revealed portions of the original historic exterior walls, recreated the original first-floor plan intended uses and updated all systems to contemporary standards.

“Gibbes came to us because they were going to have issues with future AAM (The American Alliance of Museums) re-accreditation. They could not deliver art into the building directly without going outside,” says Joe Schmidt, owner, Evans & Schmidt Architects. “We had to reorient the delivery system so trucks could safely deliver artwork directly load into the museum.”

“The recognition that the building needed renovation was clear 10-15 years ago,” says Angela Mack, executive director of the museum. “There had been prior attempts. The true essence of the original building had been lost. When I arrived in 1981 and walked in the front door after seeing the front façade, the building made no sense to me.

“We began doing research when we reached our 100-year milestone,” she adds. “It made us think about what we were missing.”

The first step was to locate the original plans at the city archives. “It took about a year to relax them,” says Mack. “They were crumpled up. Once they were relaxed and copied, they allowed us to unravel the mystery of the building.”

Schmidt and Mack realized that the original intent of the first floor had been lost and set about restoring it. “We discovered that the original museum had lecture space, classroom space and artist studios on the first floor,” says Schmidt. “So we moved all of the art exhibits to the upper floors and brought the first floor back to its original purpose.”

“It truly made us understand what the first floor was supposed to be,” says Mack. “The first floor was originally working spaces with grand exhibition spaces above. It was built like an academy so that people could learn the skill of creating art on premises with rotating exhibitions on the upper floors to copy – the traditional way of learning.”

“It also made sense for today’s needs,” Mack adds. “A museum has to have a variety of amenities, a retail store, food service, and space that can be rented for events. We were able to combine all of those functions along with our education components and the four studios on the ground floor.” The ground floor with its classrooms, studios and amenities is now free and open to the public.

Moving the galleries to the upper floors also allowed the designers to make the building more energy efficient. “We only had to maintain the 70-degree, 50% relative humidity required for art galleries – which is hard to do in South Carolina – on the upper two floors,” Schmidt explains.

One of the challenges in changing the format of the building was how to separate the first floor to maintain climate control on the upper floors and without closing it off visually. This was accomplished by adding two large (10-ft. wide x 13-ft. high) frameless arched glass doors at the two staircases leading upstairs.

Interior Elements

The two historic flanking cast-iron staircases had been an important element of the original building, but one had been removed during the 1977 renovation. “They had put in a hidden stair that took up an enormous amount of space,” says Schmidt. The 1977 stair was removed and the remaining historic staircase was replicated.

It took a while to find someone who could replicate the historic staircase. After searching for some time, Schmidt and the contractor found J&M Foundry of Summerville, SC, which also helped them restore the cast-iron public viewing gallery railings in the Charleston City Hall. The owner, Jimmy Midgett, removed the decorative pieces of the remaining staircase, recast them and then added them to a staircase that was built of plate steel. He also recast the newel posts. The treads and landings are made of Georgia Cherokee marble. “People can’t believe that one of the staircases is new,” says Schmidt.

Another historic element that was restored was the laylight in the 23-ft. high Main Gallery on the second floor. The original building had one large main gallery with one 20x40 skylight and a 20x40 laylight. “We decided not to bring the skylight back,” says Schmidt, “but we did want to restore the laylight.”

The architects studied the laylight design on the original plans and realized that they were constructed like giant wood French doors within a steel grid. Schmidt and the contractor met with the local millwork shop, Charleston Woodwork, North Charleston, SC, and asked them to rebuild the laylights. Initially the response was that they couldn’t do it. “We explained that they just had to build 12 French doors, 10 ft. 6 in. x 4 ft. 8 in., with 18 panes of glass each, then lay them on their side in the steel grid,” Schmidt explains. Due to the weight, the laylight panels were not glazed until the panels were laid down in place.

Plans call for adding LED lighting above the laylights, but it has been deferred for the time being until funds become available. “Even the frosted glass itself lightens the ceiling,” Schmidt points out. “It makes a tremendous difference.”

The abandoned skylight, however, was left alone. “It had been covered since the 60s,” Schmidt notes. “We decided it was too risky to restore it, in this climate with earthquakes and hurricanes.”

The original tile floors, referred to as “marbleithic” tile floors in the original documents, were also restored. “The original architect used that term (marbleithic), but it is actually 1x1-in. porcelain tile that was laid by hand,” says Schmidt. In the 30s it had been covered by linoleum and then in the 60s, carpet was added.

Once uncovered, the tile floors could be cleaned and repaired, using some tile salvaged from old bathrooms and other areas. The tile restoration work was done by Lowcountry Tile, North Charleston, SC. “We kept every single tile,” Schmidt emphasizes.

A significant element of the building is the stained-glass dome in the front section on the second floor, located under a copper barrel ceiling. “We had it cleaned up and now it lets in natural light through an oculus. We thought it might be a Tiffany but we couldn’t find a signature. It’s a beautiful dome,” Schmidt says.

Also restored was the 1905 quarter-sawn interior oak woodwork that had been painted. “We stripped all the paint off in the sculpture gallery,” Schmidt explains. “It was amazing how well most of that paint came off. Plantation Painters of Charleston was able to restore the quarter-sawn oak.” Where they were not able to remove the paint on some intricate elements without risk of damaging the wood, they faux grained the painted surface to match the original.

Exterior Improvements

While the 1977 wraparound addition was kept, it was repaired and parts of the original building were exposed within the addition. Schmidt explains that when they reclaimed a gallery space that was added onto the rear of the 1977 addition and convert it to a lecture space, they decided to strip the 1977 sheet rock off of the now encapsulated original 1905 exterior wall. “It was in good shape, so we kept it so people could see the original red brick exterior of the building, even though it was now on the inside of the building,” he explains. They also recreated the original windows, allowing visitors to look into classrooms and studios.

“This makes the building quite transparent,” says Schmidt. “You get the total sense of the original building.”

In addition, the 1905 limestone sills of the encapsulated building side windows were used to replace the missing sills on the rear.

One of the more noticeable areas of the exterior is the new white and gray checkered terrace and the sidewalk in the front of the building. Cast-iron fencing added in the 1950s was removed to make way for the terrace. “We talked the city into letting us pave the sidewalk all the way to the curb,” says Schmidt. “There is only one other place in Charleston with similar public sidewalk paving, the John Rutledge house. He was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.”

Also important was the restoration of the two original 1905 copper torchieres on the front steps. The original glass globes had been replaced with undersized 14-in. plastic globes. Appropriately sized new clear glass globes were found in a Habitat Restore by Dan Doyle (the lighting restoration craftsman) and then carefully sandblasted from within the globe by local glass artisan Steve Hazard of Steve Hazard Studio of North Charleston.

The building itself was cleaned and repointed and various cast limestone elements were replaced. Schmidt explains that the 1977 stucco was in worse shape than the 1905 front portion. “There were hairline cracks all over it, though it was not detaching. We didn’t want to remove it, but it had to be coated.”

The museum maintained most of its activities and programs in other facilities during the two-year period that the building was closed for renovations, moving in this summer. “We came out of the renovation pretty much intact,” says Mack. “We kept the calendar as tight as possible.”

“Our desire was to restore this temple to the arts, the oldest museum building in the South,” she says. “It has worked out beautifully. It gave us a lot of respect for the building. It is built like a rock. I am proud of the renovation. I think we have created a building that is better than it was when it was first built.”

Select Suppliers

General Contractor: NBM Construction, North Charleston, SC

Duplication of 1905 cast-iron staircase elements: J&M Foundry, Inc., Summerville, SC

Replication of 1905 wooden laylight ceiling: Charleston Woodwork, North Charleston, SC

Restoration and faux of 1905 quarter sawn white oak moldings: Plantation Painters, Charleston, SC

Tile Restoration: Lowcountry Tile, North Charleston, SC

Lighting consultant: Anita Jorgensen Designs, New York, NY

Lighting Restoration: Dan Doyle, semi-retired, illumiman@hotmail.com

Plaster Restoration: Dillon Construction, Irmo, SC

Museum design consultant: Jeff Daly Design, Ancrum, NY