Religious Buildings

Restoring the Basilica of St. Louis

PROJECT

Basilica of St. Louis, The King, known as Old Cathedral, St. Louis, MO

ARCHITECT

Mackey Mitchell Architects, St. Louis; Thomas Moore, AIA, principal

General Contractor

Musick Construction Co., St. Louis; Don Musick

The Basilica of Saint Louis, The King, was the first cathedral west of the Mississippi River, and until 1845, it was the only parish church in the city of St. Louis, MO. Its history goes back to 1774, when a plot of land was designated and a one-room log building was constructed in a town known as Laclede’s Village. The city was later named St. Louis in honor of King Louis IX of France.

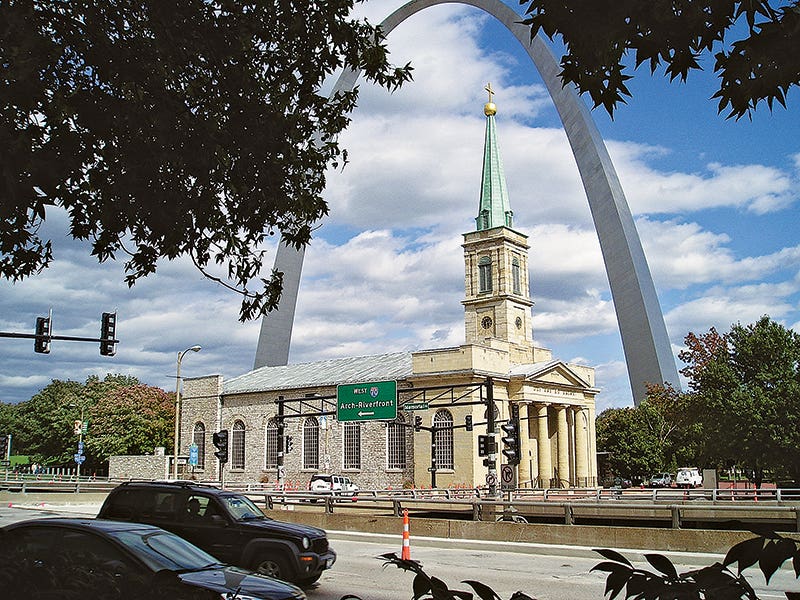

Designed by George Morton and Joseph Laveille in the Greek Revival style, the new cathedral was completed in 1834 and it became known as the Cathedral of St. Louis. In 1961, Pope John XXIII designated it the Basilica of Saint Louis, The King. Now fondly known as the Old Cathedral, it has stood the test of time and has become a beloved landmark in the city, even as all of the buildings around it were torn down to create a national park highlighted by St. Louis’ iconic arch. The cathedral is still owned by the Archdiocese of St. Louis and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Basilica of St. Louis may have stood the test of time, but time had definitely taken its toll. The stone exterior was discolored and spalling and the interior had become dingy. The firm of Mackey Mitchell Architects was brought in to restore it, along with Musick Construction Co. Coincidentally these were the same two firms that had directed a renovation and additions in 1958-61. In 2011, plans called for the restoration of the 1834 building and updating the 1960 rectory and additions. The program included stone restoration, window replacements and new HVAC systems. On the interior, it involved restoration of wood floors, removal of finishes from a 1960s renovation, new lighting, and repair of the mosaic tile floor around the altar. It was estimated that the project would cost $15 million, and it was to be funded by private donations.

“The project got started in 2007-08 when a grassroots committee was formed,” says Thomas Moore, AIA, principal, Mackey Mitchell Architects. The committee was headed up by Father Richard Quirk and one of the members was the contractor Don C. Musick, son of the contractor who had done the work in the 1960s. Also involved was Eugene J. Mackey, son of Gene Mackey, Jr., who worked with Don Musick’s grandfather in the 1960s.

“The archdiocese elected to keep ownership of the church,” says Moore, “even though it is like a donut hole in the middle of a national park. It is privately owned. Originally there were hundreds of buildings around it. They were torn down to make room for the park with the arch in the 1960s. The one building that survived was the Old Cathedral.”

Restoring the Basilica's Stone Facade

Work started on the exterior of the cathedral, which is 136 ft. long. “The south-facing front façade and about 20% of sides are made of a soft stone material quarried in Joliet IL,” he explains. “It was impeccably installed 180 years ago.”

Stone specialist John Speweik from Chicago was brought in to assess the condition and make repairs on the exterior of the Basilica of St. Louis. “He comes from family of stone masons. He really knows stone,” Moore adds, noting that the spalling was so bad that “you could see it laying on the ground.”

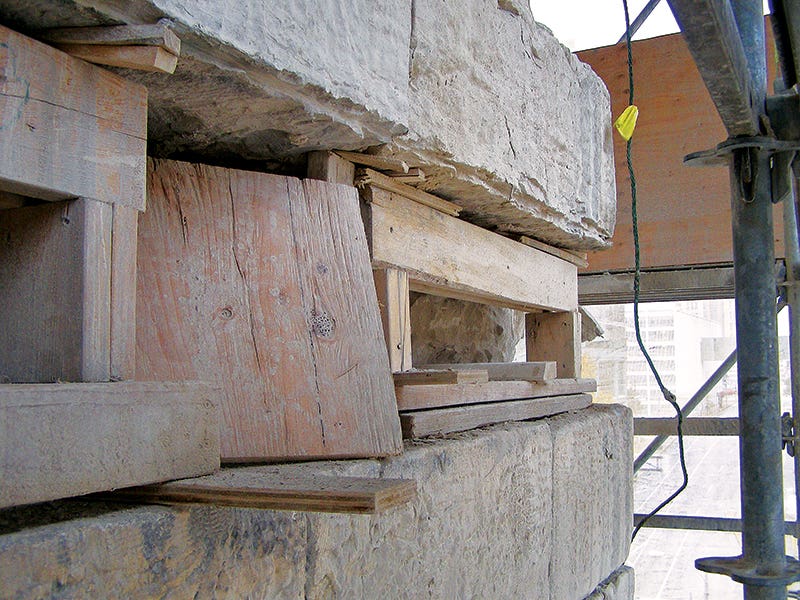

The spalling was caused by pollution from the nearby roads and by the replacement of the original lime putty with mortar containing Portland cement in the early part of the 20th century. The lime mortar was used in tight joints (about 1/8-in.) and released moisture during freeze/thaw cycles, while the replacement mortar trapped moisture, causing the stone to spall.

Speweik and his crew analyzed the stone and made repairs and replacements as needed, a job that took about 1½ years. As Moore explains it: “Using a cherry picker, we did drawings from historic information. We drew every stone on the front elevation and 20% of the sides, and then John categorized the type of restoration required for each stone, following the Secretary of Interior guidelines for historic stone restoration. That ranged from do nothing to complete stone replacement.”

The first job was to replace the existing mortar with lime mortar. Then Speweik and his crew could address the repairs in situ. He held a series of training exercises on how to remove existing mortar, and how to redress it. “No power tools were used,” says Moore. “Everything was pneumatic or hand done.”

Some of the stones had to be slid out further to keep the face of the wall flush; those were taken out, redressed and then put back. Portions of stone that were removed were re-used in the new mortar, to help match the color closely. Excess stone was also used to repair other areas.

Moore points out that a number of stones – all of the belt course and the stone that was close to the ground – had to be replaced. Limestone supplied by Quarra Stone of Madison, WI, was a close match. Other stone was supplied by Earthworks of Perryville, MO.

“It was painstaking restoration,” Moore stresses. “But it went beautifully. The workers were excellent. Some stones weighed as much as 10,000 pounds. It was quite amazing to see them take the stones out.”

The goal was not to recreate a new building. “We wanted to keep it clean, but we wanted to make it look like an aged building, not a new building,” says Moore. “We wanted the patina to show through and to halt the deterioration, and that’s what we did.”

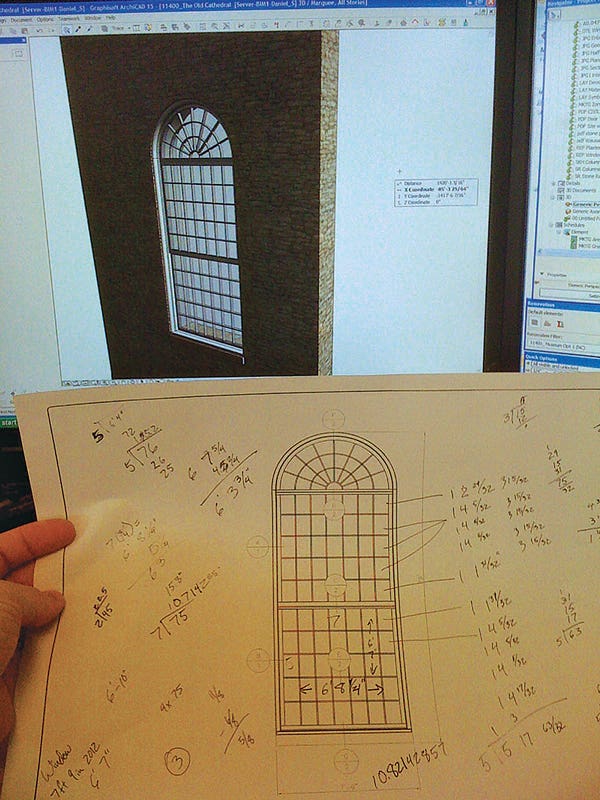

Also on the exterior, the windows were replaced. The existing 1960s windows were at the end of their life, so Moore and his team replaced them with low-e aluminum windows with insulated glass that were custom made by Graham Windows to replicate the triple-hung historic original windows. He found photos and information in old newspaper photos and in the HABS files. One last exterior item was the copper on the 45-ft. steeple. It had aged significantly over time and become unstable. The original copper could no longer be repaired, so it was replaced by Architectural Sheet Metal of St. Louis, MO.

About this time, Randy Rathert, AIA, the archdiocesan architect, joined the project. “When I got involved, the stone restoration was already under way,” he says. “I became director of building and real estate for the Archdiocese of St. Louis in 2012. I represent of the archdiocese and Father Quirk represents the parish. We are the two ownership representatives.” The project team had various ideas for how to restore the interior. “We looked at old photos and decided that there was a scheme dating back to 1890s which represented the church in St. Louis at the peak of predominance on the nation,” says Rathert. EverGreene Architectural Arts was brought in to investigate the interior and recreate it to this time frame.

They looked at historic photos of the interior of the Basilica of St. Louis, and peeled away layers of paint and canvas to find original colors. “We could have had them hand paint in place, but budget constraints wouldn’t allow that,” Rathert explains, “so they painted original details on canvas, scanned them and then reproduced them on new canvas through a printing process. The canvas was then applied it to the walls. All detail is trompe l’oeil. There is some three-dimensional plaster that remains, and it blends very well.”

Moore adds: “It looks three dimensional, but it’s not. It’s absolutely stunning. Most of it is flat trompe l’oeil work.”

Barrel Vault Restoration

EverGreene was able to save the original barrel vault ceiling. The plaster had deteriorated so it was coming off of the wood lath. The artisans cleaned and exposed the wood lath, then they drilled holes in back of it and injected a plaster strengthening solution. Then a bonding agent was injected to secure the plaster back to the wood lath.

In addition, the wood floors and pews were restored. And, when red carpet was removed, the architects found historic mosaic floor tile around the altar. They were able to restore it and replace pieces as needed.

And finally, historic chandeliers were built by St. Louis Antique Lighting Co. for the cathedral. While these are incandescent to provide a warm light, other lighting throughout is LED. Randy Burkett was the lighting designer.

“The project came in at around $9 million, not $15 million as expected,” says Rathert. “We were able to find ways to save money, mostly on the interior. And the cathedral stayed open for masses the whole time.”

“It’s a showpiece now,” says Moore. “Everyone is very happy with it. The entire team brought both inside and outside architectural features back to life, helping restore dignity to this significant St. Louis landmark.”