Restoration & Renovation

The Restoration of the Abbeville Bank and Trust Co.

PROJECT

The Abbeville Bank and Trust Company, Abbeville, LA

ARCHITECT

Paul J. Allain, Architect APAC, New Iberia, LA

With their focus on day-to-day markets, commercial businesses don’t often see profit potential in the past, but for the Abbeville Bank and Trust Company and Paul J. Allain, Architect APAC, a historic building turned out to be an excellent investment.

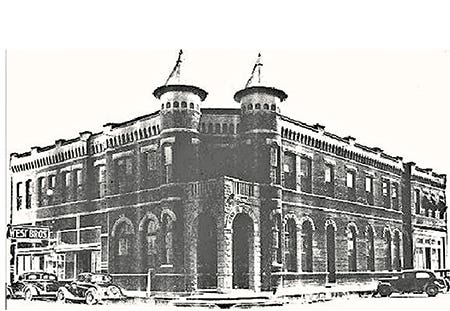

Built in 1894, the two-story Romanesque Revival structure has long been a downtown landmark in the southern Louisiana city of Abbeville, due in part to its distinctive arched corner entrance with twin towers, the design of prolific local architectChristian George Honold. Today it is a contributing element to the National Register-listed commercial historic district, but by the 2010s it was hard to speculate on its continued use as the main bank and central office.

“Because of the changes in the banking industry, the Bank of Abbeville and Trust Company had to add more employees to provide the regulatory services sought by the FDIC,” explains Paul Allain, “so the choice was to either build a new facility or stay downtown and renovate the upper level of this building, which was available.”

Fortunately, two progressive programs helped make that decision. “The driving forces behind the rehabilitation of the upper level were the state and federal tax credits available for the preservation and restoration of the building,” says Allain. “The Bank received as much as a 25% state tax credit and, because the building is listed on the National Register, they qualified for a 20% federal credit – a combined 45% credit and quite substantial.” The Bank, was also motivated by its deep roots in this agricultural community. “They are very, very sensitive to the building’s original architectural design, as well as trying to maintain the strength and integrity of the historic character of the downtown area.”

Principal to making the project work was developing the totally unoccupied, 8,000-sq.ft. space in the upper level of the building – seemingly ideal, but not before accounting for some shortfalls. Since the space had seen many uses – even a lodge at one time – it was segregated from the lower, historic bank floor, which presented a challenge for adapting it for bank use and code-required means of egress. “We had a single flight of stairs that went up 15 ft. in height, but with no intermediate landing,” says Allain, “and the stairway wasn’t protected by any fire-safe construction.”

This in turn led to what he says is a common conflict: how to bring a building up to modern code while at the same time not losing historic features that could put a tax credit application at risk. Says Allain, “We had to make the case with the historic preservation agency that, agreed, the stairway is a really important element within the building but, unfortunately, it doesn’t meet the criteria of the Louisiana State Fire Marshal’s life-safety code.”

Ultimately he says they were able to add two new fire-rated stairwells by reconfiguring a few small offices and non-essential rooms, and thereby a safe passage from the second level to the first level and directly to the exterior. “We also added a passenger elevator within the existing building footprint because, in addition to the board room usage, the public would now actually go to the second level, so it was important to have some vertical means of travel.”

Creating the board room was more about taking stock of the original architecture. “It was always a corner office,” explains Allain, “but we brought in more of the building’s exterior curvature – and those beautiful towers – by highlighting the room geometry with raised panels, wainscoting, drop-pendant light fixtures, and very tall wood doors.” He says they wanted to accentuate some of the doorways by using natural wood, but there weren’t enough existing doors to go around. Plus, not only were the doors in ragged shape, they were too thin to accept handicap accessible hardware.

“Since we had a fresh, new commercial building, we had to be ADA compliant. Today’s standard for door thickness is 1¾-in. minimum, so to make handicap accessible hardware fit a raised-panel door, we replicated the doors in the same architectural style, down to the casings around the doors and re-using plinth blocks and rosettes where possible.” Allain says all this attention to detail was important for the owner. “I think that they wanted to make sure that each passageway replicated some of the original architecture.”

The lobby downstairs, last renovated in 1980, was showing its age and incompatibility. “The lighting was terrible, the cabinetry quite dated and non-functional, and the flooring system – layer upon layer of little ceramic tile – read like a timeline of American architecture," explains Allain, adding that the ceiling, which originally was over 14-ft. high, had been dropped down to about 10½ ft.

The bank wanted to sensitively update the lobby by creating some commercial offices with lots of glass and good visibility, but being sure to capitalize on historic architectural features – especially the large, tall exterior windows and the 1894 vault. “Originally, the vault was a focal point in the lobby,” explains David J. Allain, associate designer, “but in the 1980s renovation, it got muted and blended in with the rest of the lobby finishes, so we re-emphasized the vault and the architectural language it represents: fortitude, stability in the community, and tradition.”

To this end the architects clad the vault in stone and restored the door, a featured part of the lobby. “The door dates to 1894 and is unique with a lot of character,” he says, “so we completely stripped and repainted it as well as repaired a few parts.”

The firm also improved the flow for bank customers at two important ground-level spaces. “After creating the lobby for the public teller stations,” says Allain, “we nearly doubled the width of the existing pass-through to the commercial business lobby, so now there is much better communication between the two.” Achieving that currency was easier said than done, however, because it meant increasing the opening in one of the original main bearing walls and structurally stabilizing the 120-year-old load-bearing masonry.

Tin Ceiling

A finishing touch is a new, pressed-metal “tin” ceiling that emulates the historic plaster design and is painted to complement the architectural interior of black granite and natural wood.

Like many restoration projects, however, some of the most thoughtful work leaves little evidence to show for it. Allain says when it came to modernizing the teller stations – “with all those 21st-century amenities that make banking electronic and paperless” – they took care to the conceal systems while at the same time making them accessible for upgrades down the road.

A similar hedge on the future was incorporating an emergency generator system in the building. “We’re in the same hurricane zone as New Orleans,” he says, “so when a major storm hits, it knocks out power for a minimum of a week, if not two.” Should the bank lose power then, not only would their security systems and cameras keep running, but also it would not have to shut down because, without climate control, “around here in August when it’s 100-plus degrees outside, it’s difficult to conduct business.”

The general contractor for phase 1 was J.B. Mouton, Lafayette, LA, and for phase II, it was C.M. Micciotto & Son, Lafayette, LA. The millwork subcontractor was Brian A. Hebert Woodworks, Lafayette, LA. The ceiling tiles (metal and acoustic) were supplied by Armstrong; door hardware by Yale and Schlage. TB

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.