Religious Buildings

Installing Elevators in Historic Churches

PROJECT

Trinity Church, New Haven, CT

ARCHITECT

Robert Orr & Associates, New Haven, CT; Robert Orr, FAIA, principal; Susan Bridgewater Odell, AIA, project manager

PROJECT

St. Patrick Church, Enfield, CT

ARCHITECT

Baker Liturgical Art, Plantsville, CT; Brian T. Baker, president and owner; Wojciech Harabasz, architect; Chuck Davenport, head project manager; Ed Leahy, assistant project manager; Jim Pecorelli, assistant project manager.

What’s the newest trend in church restorations and renovations? According to anecdotal evidence, it could very well be the addition of elevators. There is no historical precedent for this newly desired amenity. For generations, aging congregations were content to climb steep steps to be closer to the lord. Caskets were carried into and out of churches on the backs of broad-shouldered pallbearers, and baskets of celebratory wedding flowers were conveyed to the altar by hand.

But there is a growing awareness of accessibility issues and a feeling among pastors and parishioners that the church should welcome visitors easily. (Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, church compliance with equal-access rules is voluntary.) The elevation of elevators, as these two projects from Connecticut illustrate, is also a matter of convenience and safety. With no slippery steps to climb, everyone has peace of mind – and no excuse for staying away from the pews in winter weather.

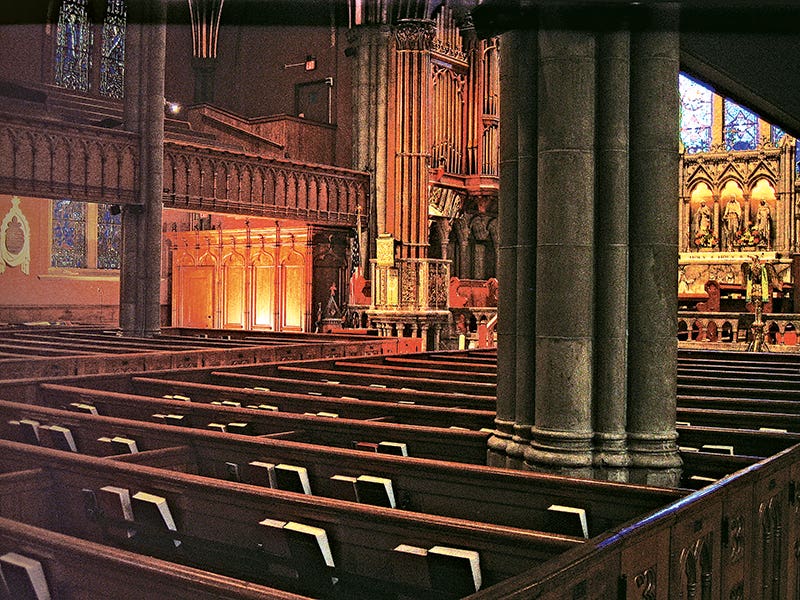

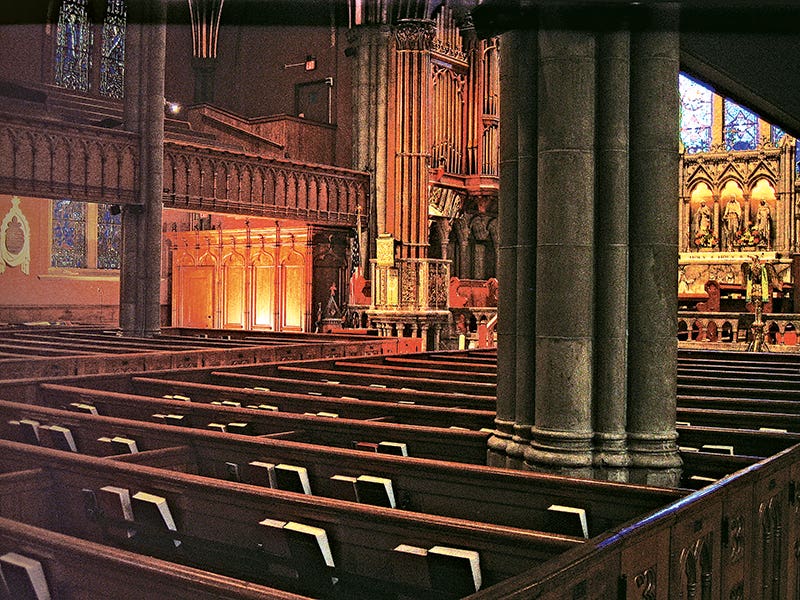

Trinity Church

Off and on for nearly six decades, the congregation of Trinity Church on the Green, founded in 1752 in New Haven, CT, had been trying to find a way to install an elevator in its sanctuary to transport the elderly and infirm between floors. The architecture was sacred. The building, designed by Ithiel Town in 1816, was thought to be the first Gothic Revival structure in America; the stained-glass windows were by Louis Comfort Tiffany; and an antique Aeolian-Skinner organ spanned the nave. The congregation has looked at plans that skirted the sanctuary, but they involved exterior excavations, making them too costly to implement.

The issue dated to 1961 when the church embarked upon a major excavation that lowered the crawl space to create a full-height undercroft for its expanding programs. Four narrow staircases that challenged even the ablest ambulants were the sole link between the spaces.

Things stayed in a state of suspension until 2007 when architect Robert Orr, FAIA, whose eponymous firm has been centered in New Haven for more than 30 years, came up with a solution that saved the architecture and satisfied the budget. Orr, who trained at Yale and held a five-year apprenticeship with Philip Johnson and then Allan Greenberg, employed the same philosophy he does in all projects. “Whether rustic or refined, my designs try to look as though they’ve always been there,” he says.

In the case of Trinity Church, Orr encountered numerous structural obstacles that added nearly a year to the schedule and a significant increase to the construction costs, which topped out at $361,500. During demolition, Orr discovered that the 3-ft.-thick masonry wall that the elevator shaft was going to straddle and the foundations of column clusters had not been underpinned in the 1961 renovation. Instead, the brilliant structural engineer, Henry A. Pfisterer, had designed a creative system of cantilevers. In addition, there were water-table issues and other “surprises,” Orr says.

“It was a simple enough project,” he says. “But all the conditions – physical, historical, code and political – made it complicated, and it took on all the effort of a project eight or ten times its size.” And size was one of the greater restrictions. “It was a challenge to shoe-horn everything into 800 sq.ft.,” he says. “It was even more challenging because the church had three renovation projects going on at the same time by three different architects. And it had to be done quickly. The original timeline was six months.”

Reconfiguring the Floorplan

By moving a bathroom and reconfiguring a stairway, Orr and project manager Susan Bridgewater Odell, AIA, made enough room for the elevator shaft, which had to open on two sides. To accommodate the other functional features – a new stair, new toilet rooms and storage and mechanical spaces – Orr had to incorporate 3 ft. of the sanctuary. But no worship space was lost: The structure he created doubles as a side altar that is used for communion during the holy days when church attendance swells. “In this way, it responds to a higher calling,” Orr says, “suitable for contributing to the liturgical life of the church.”

He enclosed the whole in an articulated custom cabinet whose Gothic Revival design was inspired by the engravings of Gothic structures made by 18th-century garden designer Batty Langley. “I selected Langley’s work for three reasons,” Orr says. “First, it was contemporaneous with the early beginnings of Trinity; second, English precedent is appropriate for a church whose roots are planted in English soil, and third, his designs explored a unique combination of Gothic and Classical forms, similar to the original architect’s Gothic/Classical detailing for Trinity.”

The white oak cabinetry, made by Eric M. Rose and Paul Carlson of Rosewood Custom Cabinetry and Millwork of Killingworth, CT, blends seamlessly with the richly ornamented architecture of the sanctuary. And that was Orr’s objective: To make the form recede into the background of church even though it makes a stately stand in the front of the sanctuary.

“A wooden cabinet is all one sees,” he says. “Although the cabinet design in its entirety does not replicate anything within the church, every one of its details finds precedence close by. The result is a new addition that looks fresh yet familiar. The familiarity is in the details, whereas the freshness is in the overall concept.”

To make the cabinetry seem as though it is what Orr calls “an organic living tradition of the church,” Rosewood matched new materials to old and used reclaimed wood when possible. The finish, achieved by a multi-step process that included bleaches, stains, glazes and hand-painted and hand-rubbed applications, “matches the mottled look of 200 years of constant use,” Orr says.

Orr was thrilled to be the one chosen to execute such a humble yet significant project. “Everyone worked together, and everyone wanted the best for the church and building for the long term,” he says. “The church has been there a couple hundred years and will be there a couple hundred more.”

And Orr will be there to mark at least a part of its passage. “I’m a longtime member of the church,” he says. “Every time I see it, I am reminded again that it contributes to the magnificent grace all around.”

A Tower Solution

In the historic village of Thompsonville, CT, (a census-designated place, CDP, in the town of Enfield) St. Patrick Church is an iconic and very visible landmark. The towering brownstone building, which has housed the Roman Catholic congregation since the mid-1880s, anchors the corner at Pearl and High Streets.

When Brian T. Baker, president and owner of the full-service design-build company Baker Liturgical Art of Plantsville, CT, was called upon to install an extra-large elevator in the structure, he knew that it would be a delicate and tricky balancing act to design an extension that would not call attention to its 21st-century nativity.

This was not the first major work that had been done on the church. In 1949, the interior of the church had been rebuilt after a votive candle caused a fire that collapsed its slate roof, destroyed its vintage stained-glass windows and gutted the inside. And, there was already a small utilitarian elevator, which was more of a rudimentary lift. It had been added decades ago, and was tucked into a side doorway to take parishioners to either the basement or the nave.

Baker’s company, which has worked on some 2,000 church restorations and renovations around the country in the last 35 years, initially was asked to design a space for a small passenger elevator for the 20,000-sq.ft. building that is home to 800 worshippers. After the plan was presented, the church decided that it wanted to expand the idea.

“The old, original elevator didn’t solve all the problems through the years,” Baker says. “The stairs leading up to the main entrance of the church are quite steep and slippery, and bringing caskets into the sanctuary for funerals is very difficult and sometimes dangerous. Father John Weaver, pastor of St. Patrick’s church, asked us to develop a solution that incorporated a dual-purpose elevator to be integrated into the existing structure.”

Baker and his team conceived a round tower similar to the ones bookending the front of the church. They positioned it on the same side of the building as the existing elevator, which was removed during Baker’s renovation. They placed it strategically between a set of stained-glass windows for the maximum aesthetic effect. “This was the perfect place for it,” Baker says. “You can drive right up to it, so it’s very accessible for wheelchairs as well as hearses carrying coffins.”

Because the church is in an historic village, the design had to be approved by the planning and zoning board as well as the town’s restoration committee. The process, which took four to five months, pulled the project into the winter of 2014, one of the East Coast’s more brutal. “We lost a lot of time because of the snow,” Baker says. “The project took us a year to complete, which was much longer than we anticipated.”

But the weather wasn’t the only challenge. The construction itself presented what Baker calls “surprises.” With the original architectural plans lost to time, Baker and his team did not know that their foundation was faulty. “When we started excavating, we discovered that it was only rocks,” Baker says. “So we had to underpin it with the foundation of the church. This added to the cost and difficulty.”

Making it Match

Getting the tower to look like the church also took time and effort. “We matched the brownstone, sourcing a couple a companies that provided remnants from bridge abutments and old buildings,” Baker says. “The only difference is that the tower looks cleaner, but it will patina with age to fit right in.”

To further the old-new look, the tower’s roof is clad in architectural shingles. “The church originally had a slate roof, but it was replaced with shingles,” Baker says.

Although the tower, which serves as the elevator shaft, has no windows, the brickwork on the front contains an outline of a Palladian window that matches the shapes of those on the surrounding walls.

The vestibule that leads to the shaft echoes the style of the church right up to the cast finial that is meant to evoke a cross.

To place the turret perfectly in the past, Baker’s team trimmed the floor-to-ceiling vestibule windows in custom oak; their aluminum frames are designed to accommodate stained-glass windows should the church wish to add them.

The pair of oak doors, which open and close automatically to make it easy to move caskets and wheelchairs in and out, feature leaded-glass panels that are in sync with the style of the vintage ones at the church’s front entry.

Part of the beauty of Baker’s plan is that it didn’t disturb the landscaping. “The most major things we did,” he says, “were corrections of the walkway and cutting in a handicap ramp.”

Although Baker has not been commissioned to design many elevator shafts during his long career, he expects to field more requests as more congregations make accessibility for all a priority. He considers the St. Patrick project a model. “You don’t see many elevators with circular towers,” he says. “It fits the building nicely. That’s what I’m most proud of.” TB