Projects

Lessons for Campus Living During COVID-19

Melissa DelVecchio is a partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects.

In a conversation with one of our academic clients earlier this year, we asked how and when the university was planning to send students back to campus and what factors would impact future decisions.

During the discussion, it occurred to me that our design for their living-learning building was better suited to new social distancing rules and quarantine situations than some of our other academic projects. Living on campus is central to the United States college experience, but student housing poses a big challenge as schools work to make their campuses safe for students throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

RAMSA has designed many residential buildings with varying layouts for colleges, universities, and secondary schools across the United States and in China, from single- and double-bedrooms with shared bathrooms to fully equipped apartments with kitchens. Looking back at these various student housing models with the current health crisis in mind can help us respond to the situation and propose better solutions in the future. For this article, three student housing models will serve as valuable case studies: shared suites designed for the new residential colleges at Yale University; single bedrooms with shared social spaces designed for a living-learning college at Tsinghua University; and micro apartment studies prepared for an unbuilt college housing project on a liberal arts campus. Each housing type is designed to offer a different level of privacy to students and reflects the culture of the institution.

Case Study: Benjamin Franklin College and Pauli Murray College, Yale University

From 2008 to 2017, our office was responsible for the design of two new residential colleges at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut—Benjamin Franklin College and Pauli Murray College. The new colleges house approximately 900 residents and were built to accommodate a 15 percent increase in Yale’s undergraduate enrollment. Residential colleges, largely modeled on the academic communities at Oxford and Cambridge, have been the cornerstone of undergraduate life on Yale’s campus since the 1930s, breaking down the larger university into smaller, closely knit communities. Prior to arriving on campus, all incoming freshmen are assigned to one of the 14 residential colleges and remain affiliated until graduation. Each college has its own dining hall, common room, library, and buttery (a late-night, student-run food service), as well as a series of internal courtyards. The colleges have a head of college and dean, both of whom are resident faculty members, living in the college with their families and guiding its many activities.

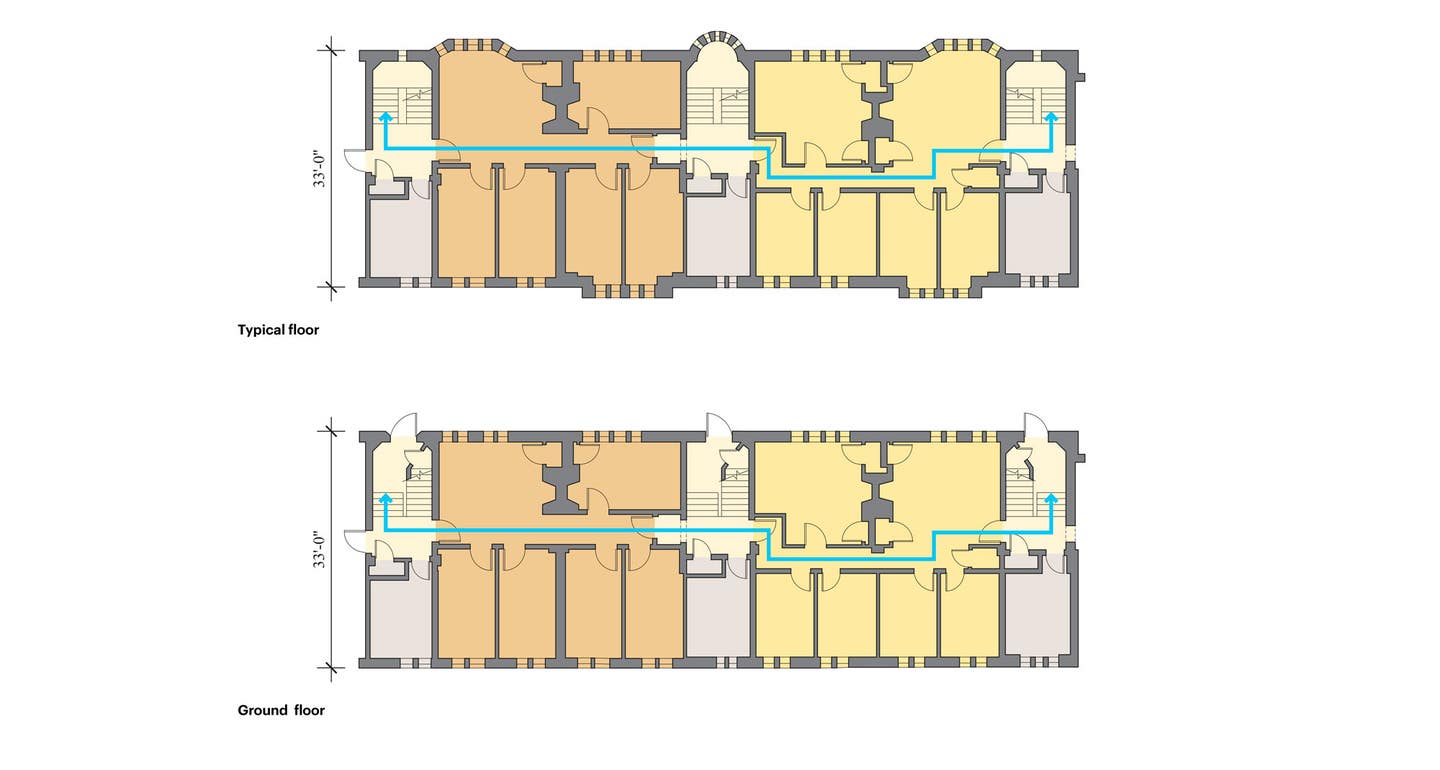

Like the original residential colleges, our colleges are planned according to the “entryway model”—an arrangement of residential units comprised of single bedrooms opening onto a shared common room, vertically stacked around a stair hall. This organization is customary at Oxford and Cambridge but rare among American colleges, where many typical dormitories are organized horizontally by floor along corridors. Yale’s student residences have long used the entryway model, from its first residential buildings in the 1700s, called Old Brick Row, to the design of the original 10 residential colleges in the 1930s, where Yale graduate and architect James Gamble Rogers’ placed entryways along enclosed courtyards. Rogers’s decision to adopt the traditional entryway model was not based on sentiment but rather on a sense of efficacy: its “many advantages for safety and convenience were so apparent that it was considered almost a requirement,” according to The Architectural Record of February 1918. The plan’s apparent convenience lay in the resulting congenial suites that spanned the full width of the building, from street to courtyard or courtyard to courtyard, thereby providing natural ventilation in warm weather and balanced heat distribution in the winter.

Both the residential college system and the entryway model offer significant social benefits under normal circumstances, and prove to be even more advantageous during the pandemic. Ordinarily, these housing arrangements build strong bonds and networks between students associated with a college and even more so with an entryway. Today, by breaking down the larger campus first, into smaller residential college communities, and second, into isolated entryways, this arrangement limits contact between students, thereby making contact tracing and containment easier and reducing spread. Additionally, because the entryway layout does not depend on a central corridor for circulation, thinner floor plates and through-floor suite layouts provide good natural cross-ventilation—this is not only beneficial for general health and wellness, but for the air exchange necessary to mitigate an airborne illness.

To meet current building codes which require two means of fire egress and accessibility for disabled students, we created what we call a “modified entryway model”—essentially two traditional Yale entryways connected by a short corridor and an elevator. This model modestly increases the student population within an entryway, with larger four or six-person end suites of double and single bedrooms and smaller double and single suites or freestanding single rooms along the central corridor. It maintains both the social benefits of the historic arrangement and is equally as adaptable for a pandemic. Bathrooms are located outside the suites, but shared only within the same entryway. This carries a social benefit for students, who can cross paths in the bathrooms, but it also provides additional safety to maintenance staff, who can clean bathroom spaces without entering students’ private quarters.

Interestingly our new colleges were used by first responders who wanted to remain quarantined from their families during the worst periods of the outbreak in early spring, when students were no longer on campus. We understand they served this purpose quite well.

Case Study: Schwarzman College, Tsinghua University

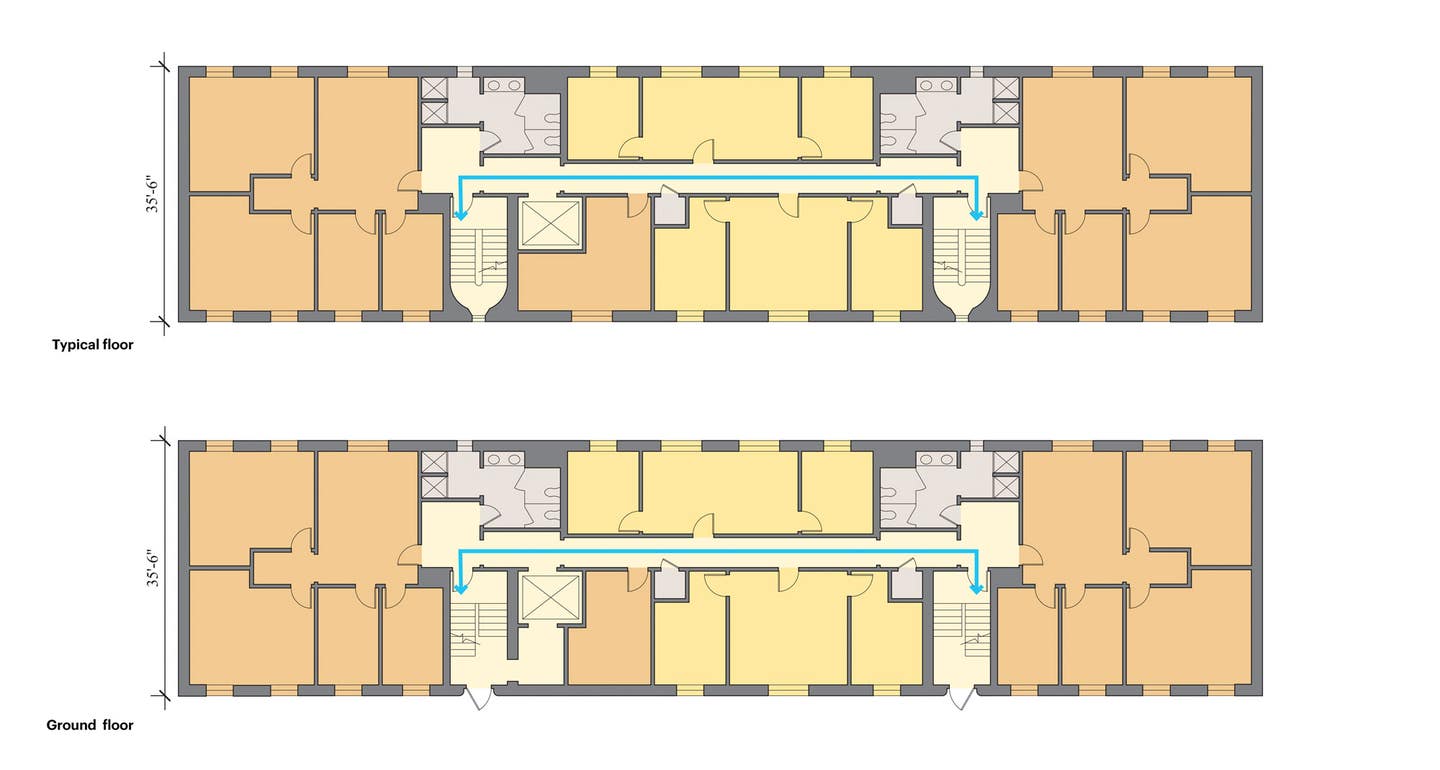

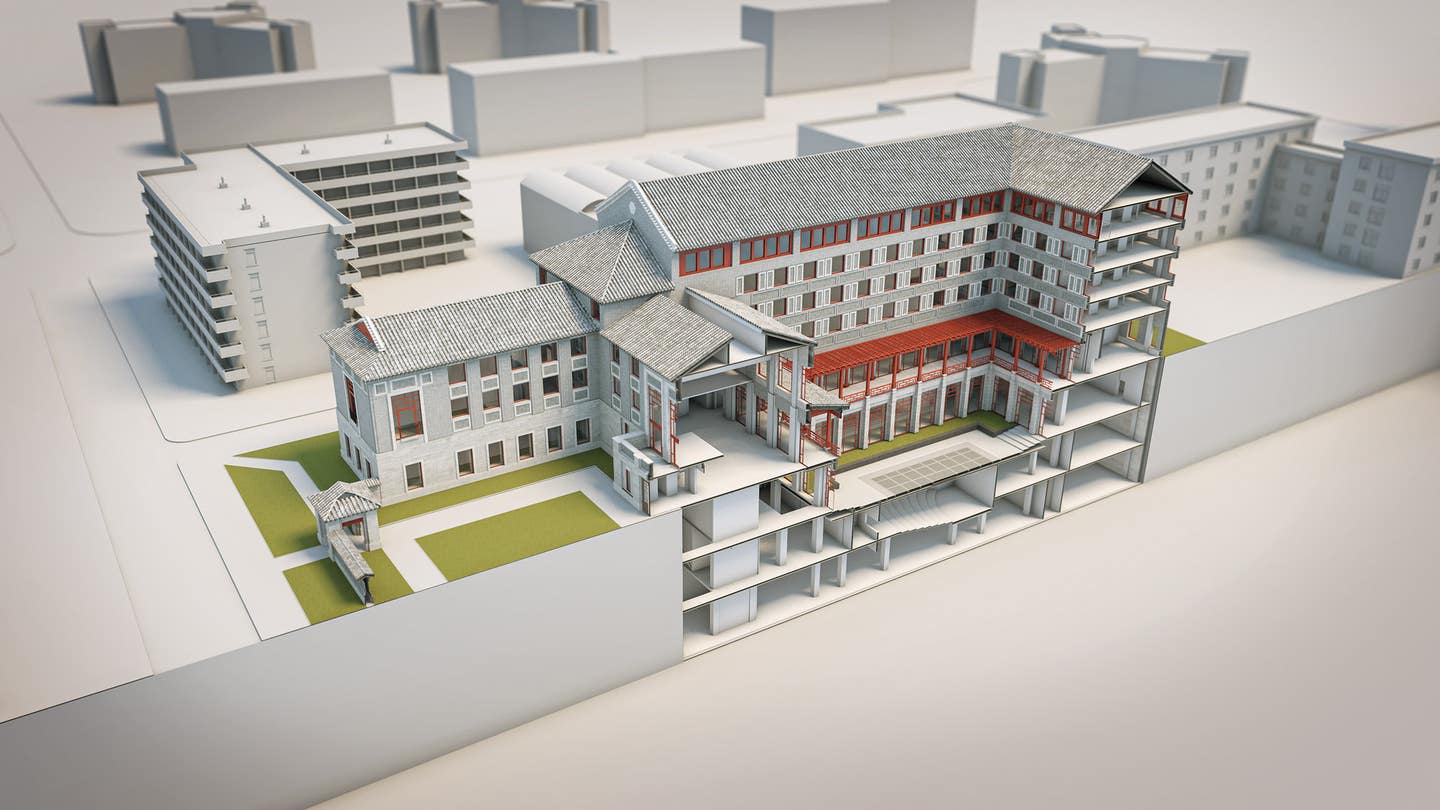

At Tsinghua University in Beijing, we designed a very different residential building for the Schwarzman Scholars program—a one-year degree for top students from China, the United States, and around the world with concentrations in public policy, economics, business, and international studies. The program is intended for students to strengthen leadership skills and to foster a deeper understanding of China in a global context. Unlike our work at Yale, which houses undergraduate students, Schwarzman Scholars range in age from 21 to 28, so many have already held jobs and lived in their own apartments prior to entering the program. The design goal was to give students the kind of privacy that one would expect in adulthood while also encouraging social gatherings in shared spaces and facilitating network-building among classmates.

The organization of the building around two courtyards again recalls both traditional Oxford and Cambridge colleges, but also the courtyard houses of China. Beyond a low garden wall with open pavilions, an entrance courtyard welcomes both scholars and visitors to Schwarzman College. Inside, a double-height “Forum” serves as a social space for informal conversations, lectures, and large gatherings. This room can be transformed for important events and easily hosts key visitors and dignitaries. The Forum opens onto a second, larger, sunken courtyard with social spaces at the main level, classrooms and an auditorium below, and student rooms located above. This central courtyard, analogous to the rear, private courtyards of a Chinese house, but modified to extend one level below ground, brings natural light to spaces located below grade.

Students live in single rooms organized in groups of eight that share a common room, intended to foster close relationships among subsets of the up to 200 scholars planned to be enrolled at any given time. This housing model is loosely based on Harvard Business School’s Executive Education housing, another educational context where building strong social bonds over a relatively short period is important to pedagogical goals and methods. Each scholar has their own bathroom, and the rooms feature built-in storage, a large desk, and a big window for natural light and ventilation (when the air quality is good outside). The rooms are intentionally small to provide for privacy while at the same time encouraging students to use social spaces. The common room features a small kitchenette and is primarily used as a place to study and socialize. Although student rooms are organized in small groups, due to Chinese building codes egress flows through the corridors and suites. As a result, the common rooms are not internal to the eight-person subgroups or strictly assigned, so students can easily move between social groups. The design of the Schwarzman College residential units is more like a traditional hotel room, with access to shared amenities and opportunities for students to come together as a whole community in the main public spaces like the Forum, library, and dining hall. For example, all main meals are taken together in the dining room and a pub at the lower level provides space for student-led activities and socializing in the evening.

This plan is very adaptable to COVID-19 safety protocols. Distribution of students on different floors allows for isolation of the student community, and the separate common rooms can be easily demarcated as quarantined areas if necessary. Private bedrooms and bathrooms allow individuals to quarantine more easily, and faculty apartments are located away from student areas. Although this layout involved additional cost, in this case it was considered a requirement due to the older age of the students and it has become an advantage in terms of flexibility and adaptability. Unfortunately, due to international travel restrictions, most Schwarzman Scholars have not been able to return to campus and the program’s staff has had to be creative in providing an immersive and community-building experience in a remote setting.

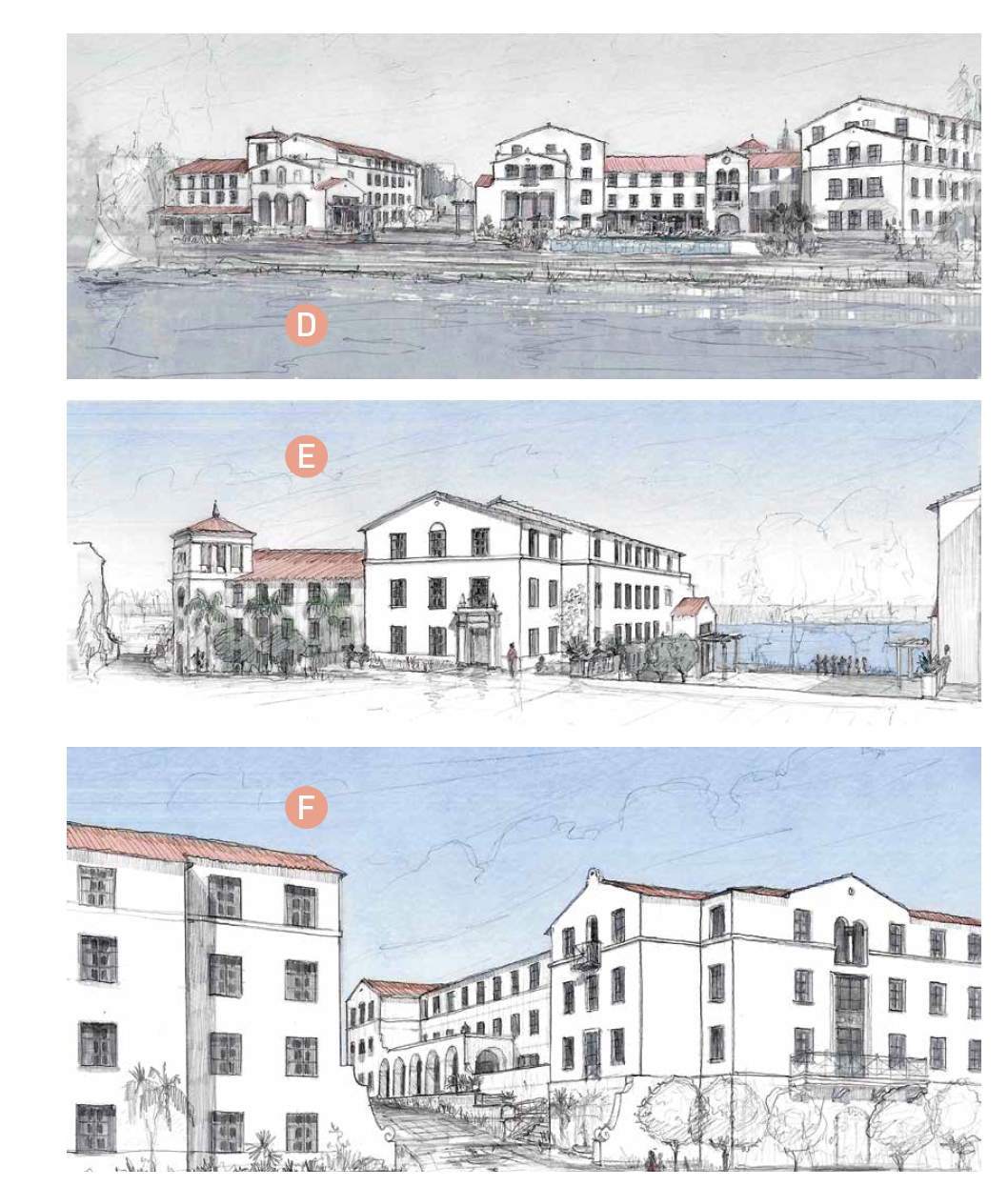

Case Study: Proposed Student Housing for a Small Liberal Arts College

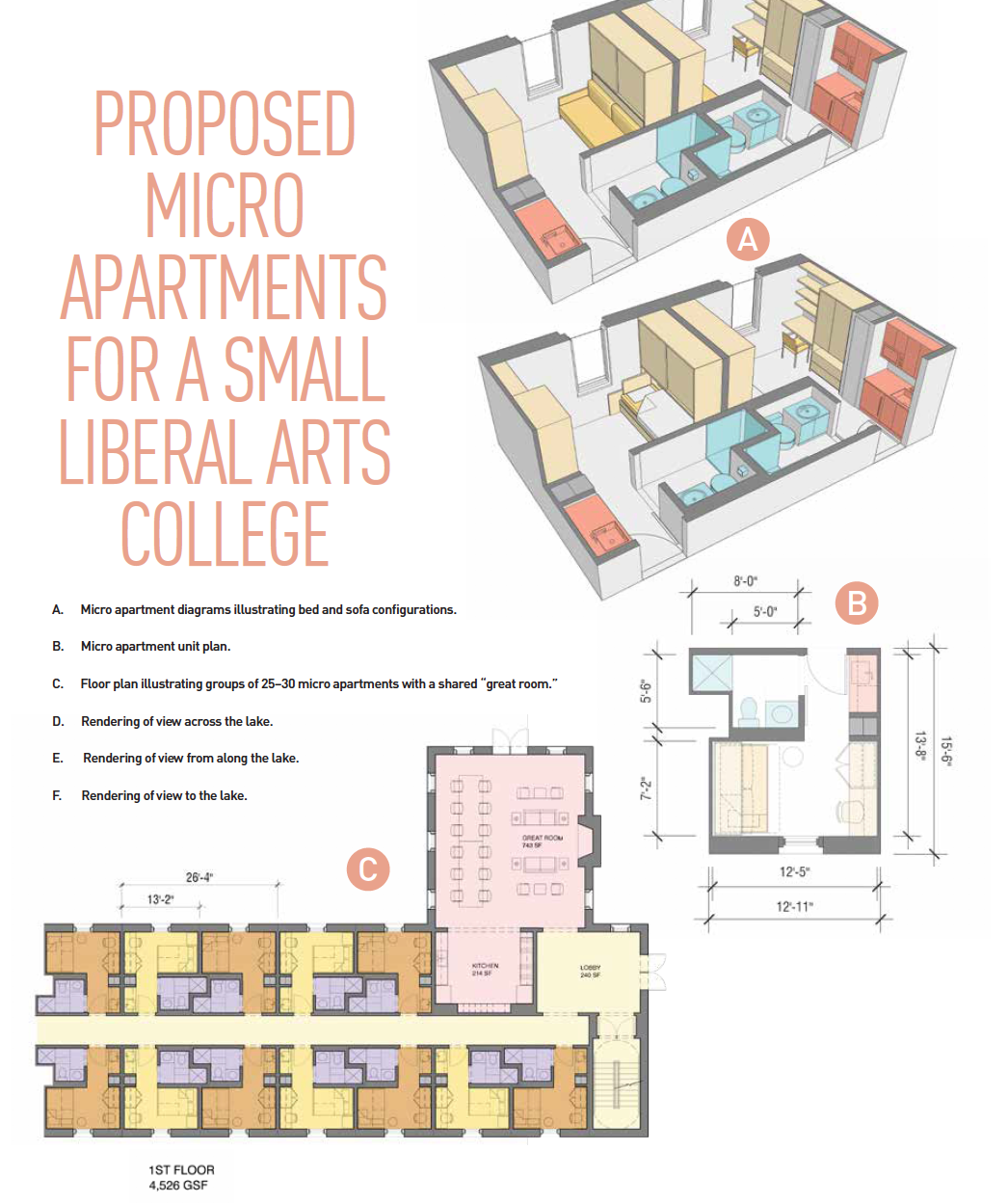

Housing studies we prepared for an unbuilt college project on a small liberal arts campus push the idea of increased levels of privacy for individual students even further than Schwarzman College. As set by administrators, the project was to be housing for third- and fourth-year students that would foster maturity and prepare students for life after graduation. But how is that accomplished in a way that still gives students the independence they crave and also offers useful shared social spaces to build community? From a mental health and wellness point of view, the school was interested in exploring options beyond shared student apartments, something that could bring together larger cohorts of students and be more inclusive.

This campus had a tradition of small residence halls, many of which had been converted from old sororities and fraternities. We carefully studied these buildings, which tended to bring together groups of 25–30 students in single bedrooms arranged around a shared common room and kitchen, and used them as a model for a new series of residential housing studies. Another precedent for this work was the Arcade Providence Micro Lofts in Providence, Rhode Island. Previously a historic shopping arcade, Northeast Collaborative Architects renovated the building in 2013 and transformed the upper floors into a series of micro apartments. We thought this idea of micro apartments would work well with the project and applied it to our housing studies.

We designed micro-sized apartment modules that could be used in place of a typical single bedroom and arranged them in groups of 25–30 with a shared “great room,” a lofty common living room and study space open to a large display kitchen where students could cook and eat together or be instructed in nutrition and cooking by trained chefs. Smaller quiet study rooms were also provided on each floor.

The micro apartments at the upper levels, each about 200 square feet, contained a murphy bed that folded into a sofa, built-in storage and a desk, a small kitchenette that allowed for some personal food storage and preparation, and a small private bathroom. These student rooms provided the kind of privacy that students want in their final years, while also providing an expanded social unit with the shared kitchens and amenities. The residential groups were arranged around a series of courtyards and other amenities to be shared by the entire complex. The outdoor amenities included vegetable and aromatherapy gardens, meditation gardens, a fire pit, a swimming pool, and indoor and outdoor exercise facilities with a juice bar. The complex also included office spaces to house mental health staff, diversity programs, and other academic support functions.

This project was not realized, partially due to the cost of the plumbing required for the micro apartments. Yet, it’s easy to see how that cost consideration might be different now given the flexibility afforded by the plan. Each residential unit of 25–30 students could be considered a “pod,” with quiet study rooms that could accommodate small seminars or allow some form of hybrid learning. The micro apartments would allow students to isolate if quarantine was required, the pods would contain potential future infection, and the array of indoor and outdoor amenities would safely maintain social connections within and outside of their unit.

Conclusion

In spring 2020, universities were forced to switch to remote teaching in a short amount of time and under tremendous stress. This shift was successful in many ways but was not representative of a viable long-term learning model. By examining various existing student housing models through a new lens, it’s clear that certain layouts and community types offer more adaptability and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as more opportunity for successful remote learning and hybrid social situations. At this current moment, it seems clear that 500-person lecture halls will become a thing of the past, suggesting that one of the oldest models for university education, the Oxford/Cambridge tutorial method, with smaller social and educational communities, might return. I hope that this article sparks a new way of thinking about how student housing can be both more flexible and a more intentional component of the college learning experience. Colleges and universities should explore new living-learning models that leverage the best of in-person learning with the best of remote learning to support society’s “new normal.”