Public Buildings

Architexas Revived the Harris County Courthouse

PROJECT

Harris County Courthouse,

Houston, TX

ARCHITECT

PGAL, Houston, TX; Ruben Martinez, senior associate

PRESERVATION ARCHITECT

ARCHITEXAS, Austin, TX; Larry Irsik, principal in charge; Susan Frocheur, project manager

GENERAL CONTRACTOR

Vaughn Construction, Houston, TX

By Martha McDonald

Built in 1910 in the Beaux-Arts style, the Harris County Courthouse in downtown Houston, TX, is one of the most significant historic courthouses in the state. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and is a registered Texas Historic Landmark and a State Archeological Landmark.

The elegant, 152,936-sq.ft., six-story structure was designed by Charles Edwin Barglebaugh of the Dallas firm of Lang & Witchell. It is a square building with a 100-ft. high central rotunda topped with a dome and lantern. The four facades are similar, with pediments, Corinthian columns and monumental stairs leading to the main-floor entries. The base of the building and the monumental entry steps are faced with rough-cut pink Texas granite, and the upper portions are faced with brick with terra-cotta accents at the cornice, railings and sills. It is one of the most prominent historic buildings in downtown Houston.

Throughout the years, however, the courthouse has suffered a number of indignities. Normal factors such as age, use and pollution contributed to the deterioration of this grand building, and a renovation in the 1950s removed most of the historic fabric in the interior and significant elements on the exterior. The good news is that the historic building has been saved and restored, as much as possible, to its original 1910 condition, thanks to a $52-million, seven-year restoration, completed in 2012.

Leading the restoration and renovation of the courthouse was PGAL of Houston, TX, with ARCHITEXAS of Austin, TX, the preservation architect. “PGAL was the prime architect, and we were the preservation architects,” says Larry Irsik, ARCHITEXAS, principal in charge. “We were responsible for historic research and restoration of the exterior and of significant historic interiors, including all of the public spaces such as the courtrooms and the rotunda. We provided general historic consultation throughout the building.”

“The design intent was to restore the exterior and primary interior public spaces back to their 1910 original form, and to renovate secondary spaces to increase functionality, and to introduce modern technology, sustainability, accessibility, fire safety and security features throughout the building,” says Irsik. Original drawings, historic photos and remnant historic materials helped the team accurately restore or reconstruct missing and severely damaged elements, but in many cases, there was very little to go on.

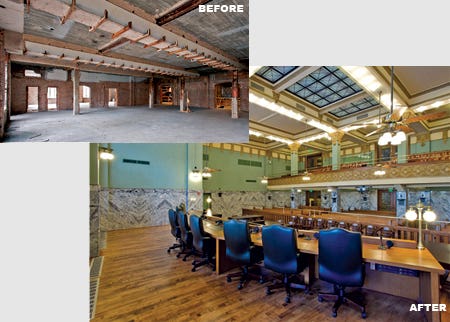

When the ARCHITEXAS team arrived, they faced a six-story historic building that had been drastically altered, mostly by the renovation of the 1950s. Floors had been added at each level in the rotunda, closing off the area to natural light that would have come in through the original 80-ft.-dia. art-glass dome. The art-glass dome was gone too; it had been removed because of hurricane damage.

That was just the beginning of the damage done by this renovation.

Floors had been added to the two historic third-floor courtrooms, dividing the once two-story monumental spaces. And, all of the original historic finishes had been removed from these rooms, including plaster capitals, balcony facing, the cornice, wall friezes, book-matched marble wainscot and wood flooring. In the rest of the building, the addition of new (1950s) heating, ventilation and plumbing destroyed the historic detail.

On the exterior, two of the monumental stairs had been removed, the stone retaining wall at the perimeter of the site had been removed, and open loggias on the second-floor entries had been closed in. In addition, terra-cotta balustrades, brick and stone masonry piers, and ornamental cast-metal lampposts on the third-floor loggia had been removed. All of the wood windows and doors, both interior and exterior, had been replaced, and the skylights over the east stairs had been removed, along with the light courts that had provided natural light into the third-floor courtrooms. And finally, the copper finial capping at the top of the lantern had been removed.

“We started on the project at the end of 2004,” notes Susan Frocheur, ARCHITEXAS, project manager, “and we spent 1½ years just on the demolition of the interior and surveying the exterior, removing non-original walls and finish assemblies that had been added in order to expose original materials. During the demolition, one piece of trim with its original stained finish was found in the interior of the entire building. The finish for stained elements such as the doors, windows, standing and running trim, etc., was based on this piece.”

There were some historical guidelines available. “Early in the 1920s someone had copied the original drawings of the courthouse,” says Irsik. “We also studied two other courthouses designed by the same architectural firm from the same construction period to determine the appropriate design/detailing for elements that no longer existed, including door and window assemblies, hardware, the art-glass dome and built-in furnishing. It all helped with the interpretative reconstruction.”

The exterior work involved replicating and replacing a number of historic features. The most prominent of these were the monumental stone entry stairs on two sides of the building, on Fannin and San Jacinto Streets. When the stairs were removed in 1952, the entries had also been moved to the basement level. These stairs, and the corresponding entries, were reconstructed by United Restoration and Preservation, Fayetteville, GA. The two sets of entry stairs on the other two cedilla facades were disassembled and reconstructed on new foundations by United. Although they were still in place, they had settled and developed structural damage over time.

During the survey of the exterior, the architects found that the terra cotta had been coated with a water-proof coating. The coating had to be removed before they could determine the condition. Terra cotta balustrades, brick and stone masonry piers, including the terra cotta railing at the dome level, were reconstructed with replacement material manufactured by Gladding, McBean of Lincoln, CA.

The remaining terra cotta was repaired, using products such as Jahn M100, (supplied by Cathedral Stone Products, Hanover, MD), and chemical cleaning products from Prosoco of Lawrence, KS.

All of the exterior windows were reconstructed of mahogany and faced with long-leaf pine on the interior to provide a durable assembly and to match the original wood species where visible. All of the doors were also reconstructed. The windows were reconstructed by Bauhaus, LLC, Lubbock, TX, and the doors were reconstructed by Beaubois, Quebec, Canada.

Also on the exterior, ARCHITEXAS replaced the ornamental cast-metal lampposts that had been removed at the third-floor loggias. “The small piers at the entries originally had light posts,” says Irsik. “We had these replicated in cast aluminum. We had only one fuzzy historic photo and we worked with Robinson Iron to get the profile correct.”

Other exterior work included installing the copper finial on the top of the lantern, and replacing the stone retaining wall at the base of the perimeter of the site. The copper cap was reconstructed from the original by the county under an earlier project but had not been installed due to the poor condition of the lantern. Following replacement of the concrete structure and repair and replacement of the terra-cotta cladding, the copper cap was installed.

Clay tile for the roofing replacement work was supplied by Ludowici Roof Tile, Lexington, OH, and the work was done by Gulf Star Roofing and Sheet Metal of Houston, TX. “During the demolition, we found remnants of the original terra-cotta tile and were able to determine the color and shape of the roofing tile,” says Frocheur.

Meanwhile, the damage done to the interior by the 1952 renovation was extensive. The first thing the ARCHITEXAS team did was to remove all of the non-historic floor slabs in the six-story rotunda, opening it once again to its 100-ft. high grandeur. Then all details had to be re-created. Marble-clad and cast-iron railings were reconstructed, and damaged and missing marble veneer at the piers was replaced to match existing material. This marble came from the same quarry that had supplied the original material, Georgia Creole Marble, Tate, GA.

In addition, the massive ornamental plaster capitals that had been on top of each pier were severely damaged at the center of each piece by mechanical ducts. Molds of the capitals were made by Matt Henson of Professio, Lubbock, TX, and the missing central ornament was designed based on other plaster ornament found throughout the building. Reconstructing the art-glass dome was a significant challenge. The architects had no historic evidence or photos to follow, with the exception of indentations in the base of the concrete piers from the original steel structure. These, at least, indicated the shape and general curvature of the dome.

They visited two other Texas courthouses that had been designed at about the same time by the same architect, the Johnson County Courthouse and the Cook County Courthouse. They both had art-glass domes, but in two different styles – Art Nouveau and Prairie. The ARCHITEXAS team decided to go with a Prairie-style art-glass dome for Harris County. I.H.S. Studios, Fredericksburg, TX, worked with the architects to detail and construct the new art-glass dome.

“The skylight was interpretative,” says Frocheur. “It was based on our experience and on other courthouses. We were able to put together something that was in keeping with the style of the courthouse. The colors in the art glass were taken from the borders of the mosaic tile flooring in the rotunda.”

Another significant challenge was the restoration of the two historic third-floor courtrooms.

Once again, non-historic floor slabs had been added, drastically reducing the ceiling heights. In addition, the curved balcony in the north courtroom had been removed, and art-glass lay-lights had been floored over.

The ARCHITEXAS team first removed the floors, restoring the original ceiling heights. “Both of the courtrooms had sub-dividing floors that had been added in the 1950s,” says Frocheur. “Like the non-historic rotunda floors, they all had to come out.” Then they began the job of re-creating the rooms, with guidance only from historic photos. There was no historic evidence left in the rooms; built-in furnishings, dividing rails and theater seats were all gone. Ghosting on the wall from the original balcony helped the designers determine the original profile.

ARCHITEXAS also re-created the laylights between the fourth and fifth floors in these courtrooms with a three-level solution. A plank glass floor was installed above the courtrooms; below that a fire-rated system and below that a decorative laylight that is artificially lit from the space above. “Originally there was a light shaft to provide daylight into the courtrooms,” says Frocheur, “but the program did not allow for the removal of valuable square footage to reconstruct the light shafts, so we installed a walkable plank glass floor system in the area above.” The spaces above the restored courtrooms, with their new glass floors, are now entry lobbies to office suites. Replacement mosaic tile flooring for the rotunda and main corridors was manufactured by American Restoration Tile, Mabelvale, AR, and the restoration work was done by Camarata Masonry Systems, Houston, TX.

Interior millwork and exterior doors were fabricated by Beabois Canada, Inc. Flat plaster restoration throughout the building was done by Golden West Enterprises, The Woodlands, TX. Ornamental cast plaster was reconstructed and repaired by Professio, Lubbock, TX.

The restoration work was approved and funded by the Texas Historical Commission under the Texas Historic Courthouse Preservation Program (THCPP). Frocheur notes that this was one of the most extensive restoration projects that she had worked on. “There were so many different materials in this one building,” she says. “We had to find many different craftsmen. That made it really interesting, dealing with so many different trades people. They worked on everything from the grand entry steps to the ornate interior marble and the plaster restoration.”

“We used the greatest number of the trades we have ever used on a single project,” Irsik agrees.

Although the project did not apply for LEED accreditation, it did follow energy-efficiency guidelines, such as using high-efficiency mechanical systems and low-E insulated glass. In addition, mold, asbestos and lead were remediated and all paints, finishes, furnishings and materials were non-toxic and sustainable. Original materials, where remaining, were restored.

The First and Fourteenth Courts of Appeal now occupy the restored courtrooms, dispensing justice in the historic two-level courtrooms for the first time since 1950s. And, daylight now shines through the new art-glass dome, lighting the restored marble-clad rotunda all the way down through the six-floor rotunda.