Projects

Digging Deep

How do you renew and enlarge a revered historic college building to meet 21st-century needs without overriding its collegiate Gothic style? That was the challenge Yale University faced in repurposing a 90-year-old complex, with a long history of residential and classroom use, in order to consolidate far-flung academic departments into a new Humanities Quadrangle.

Led by architect Ann M. Beha, FAIA, of Annum Architects in Boston (formerly Ann Beha Architects), the almost four-year project was as much innovative expansion and adaptive reuse as it was subtle restoration. “The humanities vision is that those studies—philosophy, literature, religion, history, languages, classics—be completely interdisciplinary and collaborative,” explains Beha. “But at Yale they’ve never all been in the same building before; they were distributed all over the campus.” The Humanities Quadrangle resolves that dispersion by gathering 15 departments and programs under one roof. The design team, with Yale Facilities, and Skanska as construction manager, set a high bar for design excellence and project delivery.

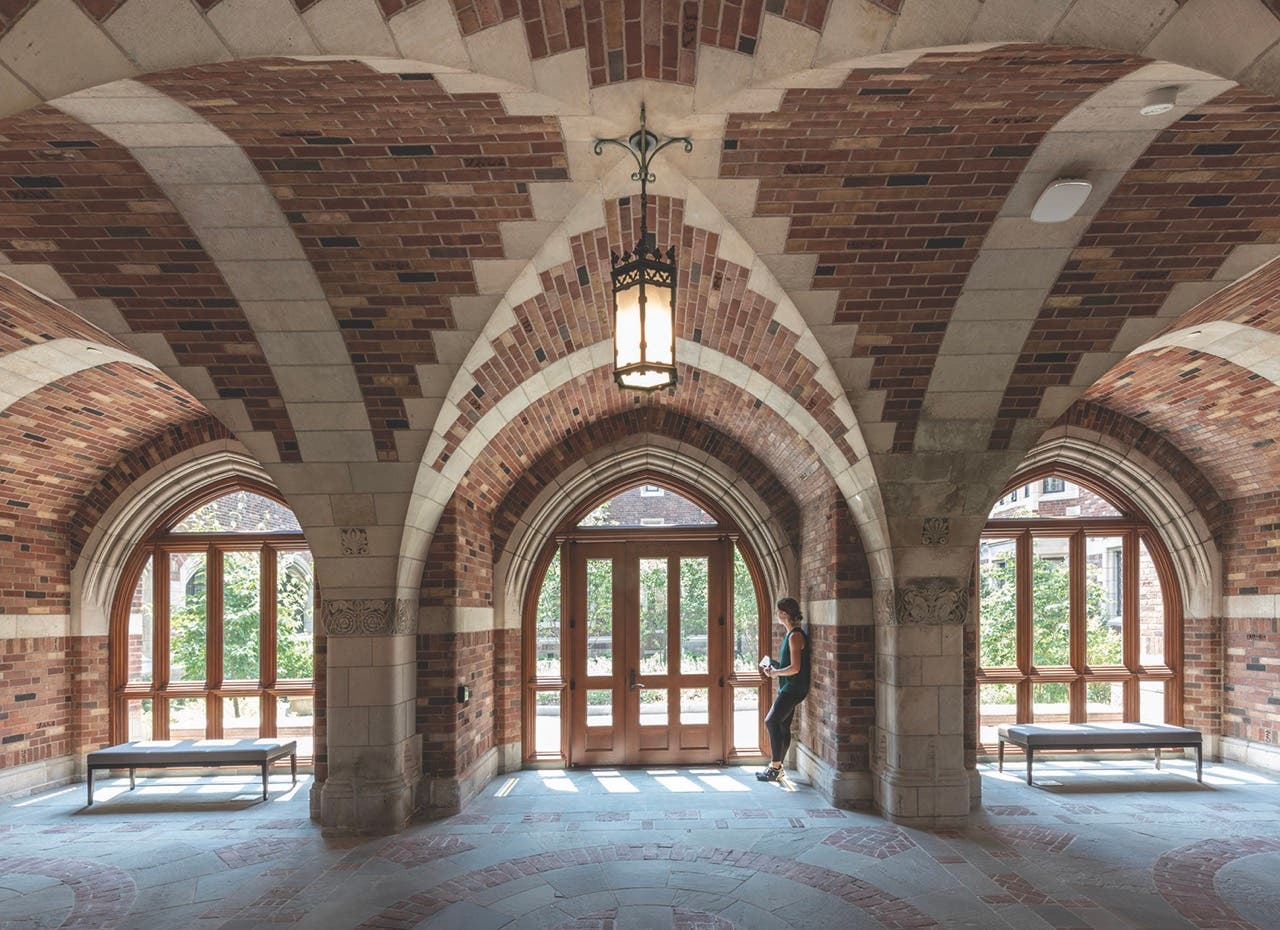

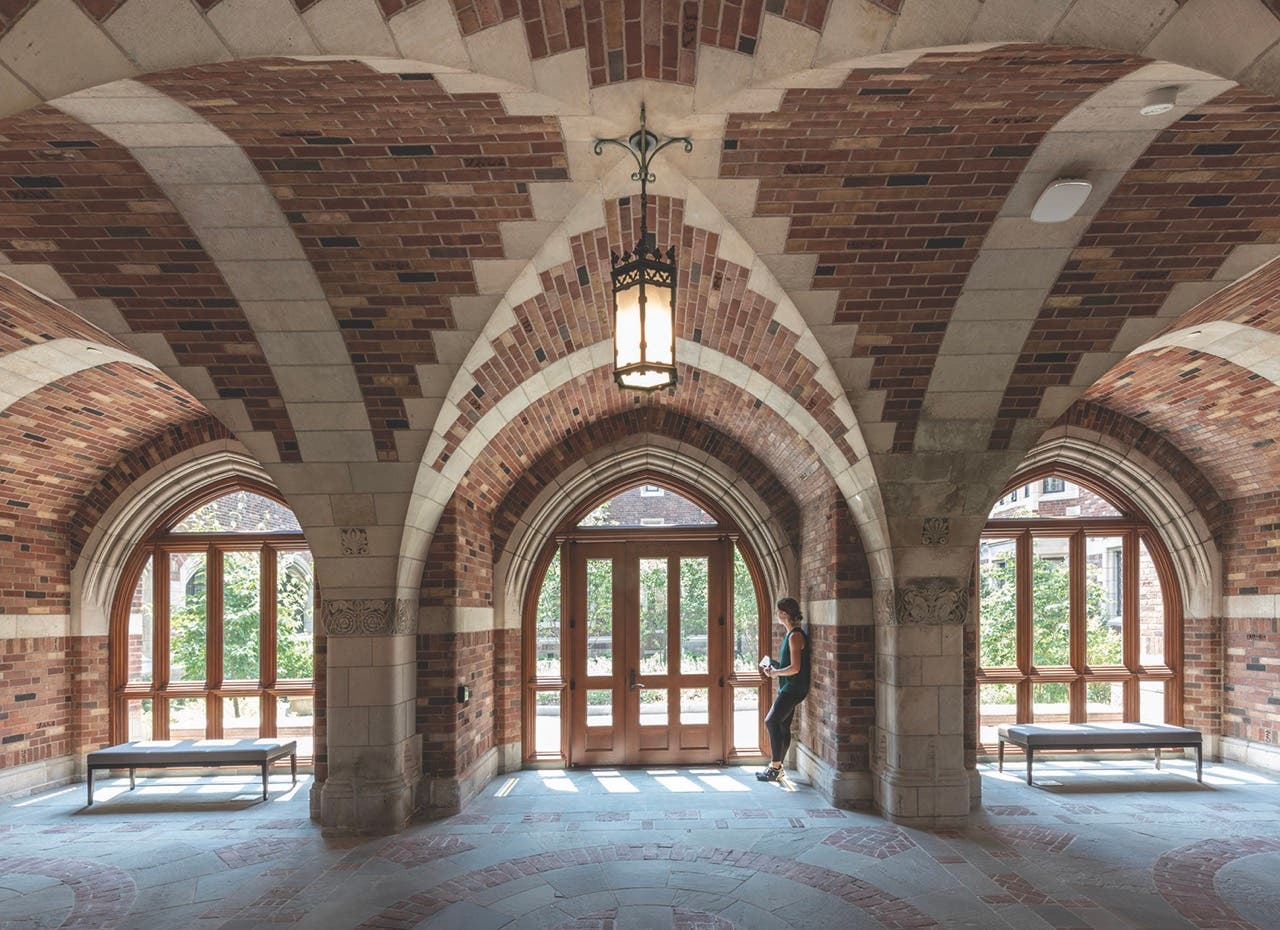

Completed in 1932, the one-time Hall of Graduate Studies was designed in the collegiate Gothic style by architect James Gamble Rogers, the master builder behind much of Yale’s historic campus. “There were four distinct precincts or individual wings of the building originally,” explains Beha, housing a mix of departments and graduate student housing in a divided cellular plan. “Now, because of the changes we made, the connections are more intuitive.” The embodiment of that approach is the York Street entrance and loggia. “Formerly, it was always open air, but in order to connect the two sides of the building, we enclosed two loggias as a walkway, so now there is a flow, an easy and watertight connection.”

Critical to the project was enlarging the original complex by some 13,000 square feet—all below grade. Beha’s design approach has turned to excavation on a number of past projects, including at Cornell Law School. “It’s a way of accommodating contemporary uses while preserving as much adjacent building and land as possible,” she explains. “This new footprint helps to connect various building levels—and at Yale, those connections are very important.”

The new lower level provides a 190-seat lecture hall and a film screening studio for 90 viewers, but capturing that extra room was not without obstacles. When asked if the excavation had to plan for any challenges—groundwater, for example, or underpinning—Beha’s candid response is, “All of them!” The details of such a complex construction feat are beyond the scope of this article, but to put the excavation in a word, that word is deep, and on two levels. The first, called the concourse level, was originally the basement and is now fully utilized as offices, classrooms, and informal gathering spaces. “Then, below the courtyard, is the excavated basement for the lecture hall and film screening room,” says Beha. “So, when you think about the lecture hall, and you see the 20-foot-high ceiling, you realize that it’s a very deep excavation—20 feet below the basement that was already there.” Along with artificial lighting the lobby gets natural light via a skylight that goes up to the new courtyard.

As if that weren’t enough, the excavated space is under one of James Gamble Rogers’s iconic Oxford/Cambridge-inspired courtyards surrounded by the enclosed quadrangle. “It presented our talented design team, and construction manager, some complex construction challenges,” says Beha, “just getting the heavy equipment—cranes, extraction equipment, concrete—through the building portals and into the courtyard.” Equipment and materials were often brought in as parts, then assembled on site. “There’s no way to get a crane through a door!” she says. “Our team was inspired by the construction approach.”

Elsewhere, the rehabilitation rose dramatically above ground, reaching 14 stories in what is now known as the Swensen Tower. “The whole tower’s graduate student residential rooms are now workspaces and open meeting rooms,” says Beha. “We widened corridors and added many more gathering spaces.” She adds, “Since the building is now centrally air-conditioned, the team had to find chases to accommodate the new systems, which always involves careful renovations and unexpected hidden conditions.”

Repurposing and renewing existing spaces, however, required a different order of business. “The planning phase was critical. We developed a preservation framework for the building—a research project that identified existing and historic conditions of the building and assessed their importance—significant, contributing—clarifying their materials, condition, and repair needs.” Beha says that’s the way she works if the building doesn’t have a Historic Structures Report: It’s specifically architectural to guide the project requirements (scope and repair methods), color coded, then translated into the project specifications. Working with a Rogers building requires broad knowledge. Rogers incorporated carved wood, tile, slate, plasterwork, decorative painting, unique light fixtures, and metalwork all in need of repairs and preservation.

Windows were a major component with more than 2000 original leaded glass units either upgraded or replaced in kind. “More than 300 stained-glass windows were unique and extraordinary,” incorporating the same lines. “All of the lighting fixtures were sent out, rewired, relamped, refinished; and the painted glass medallions that relate to science and humanities at Yale went out to several conservation shops since no one shop could take them all.”

Another dimension to the project was working with companies and suppliers engaged largely in conventional construction and not always set up for historic buildings. “Rogers gave us a kind of playbook of extraordinary materials to deal with, and the team had to find the vendors, propose the quality of finish, review the sampling, she explains. “Partnering is all part of Yale’s Humanities academic vision, and the building design aligns with those values—supporting tradition and welcoming innovation. TB

KEY RESOURCES

Architect: Annum Architects

Construction: Skanska Construction

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.