Public Buildings

David M. Schwarz Designs a New City Hall for Alpharetta, GA

PROJECT

Alpharetta City Hall, Alpharetta, GA

ARCHITECT OF RECORD

Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart Associates, Inc.

DESIGN ARCHITECT

David M. Schwarz Architects, Inc.; Michael Swartz, AIA, principal in charge; Sean Patrick Nohelty, AIA, project manager

GENERAL CONTRACTOR

Choate Construction Co., Atlanta, GA

What’s to do when a venerable, medium-sized city has prospered to the point it’s not only outgrown City Hall, but there is no longer any “there” to its downtown? A look at how David M. Schwarz Architects, Inc. tackled the problem provides some interesting ideas and solutions.

Dating to the 1850s, Alpharetta is a thriving northern suburb of Atlanta that served as the county seat until the 1930s. With continued growth, however, the city realized it needed more than just updated government offices. “Actually, the project was described as Alpharetta City Center,” explains Michael Swartz, AIA, principal in charge, “because the city had acquired about 20 acres where they wanted to build a new city hall and a new library, with the rest to be park space and commercial development.”

Like many a longstanding community, Alpharetta’s retail, restaurant and commercial space was now primarily in shopping centers on the periphery. “Downtown there were still a couple of restaurants and businesses, but nothing really substantial, so the city saw this as an opportunity to create more of a center for their community – more of a true downtown that would attract people on a regular basis.”

Swartz says his firm wasn’t hired to design the library or the private development portion, but they were charged with creating a master plan that would be attractive to commercial developers. “It’s an interesting mixture of a public-civic commission and private development,” he says, “so we had to figure out where things should go.”

He adds that while they have designed small city government buildings, that alone was not what made the match with the project. “We’re a generalist firm, and we were able to offer our experience doing successful office-commercial, retail, and restaurant developments in other parts of the country.” Indeed, he says they spent probably the first four months working out the master plan with the city, coming up with different concepts for how to organize the different parts of the site and, especially, where to locate City Hall (more on this later).

Once the site master plan was approved, the focus became City Hall and its need for more space. “The existing City Hall was a quarter or less the size of the planned one, and the rest of the city government was spread among multiple buildings over town,” says Swartz, “so we were able to consolidate a lot of different departments into one building.” What’s more, what space the government had was comically inadequate. “The city council meeting room was so tight, you banged your chair into the wall before you could pull it out from under the table.” Moreover, the council chamber itself was long and narrow like a bowling alley, so anyone sitting back at a meeting was a long way from where the mayor and council sat. “We increased the seat count but, more importantly, people now have a space where everyone can be seen, and they can see who’s presenting at city hall meetings.”

The Essential First Floor

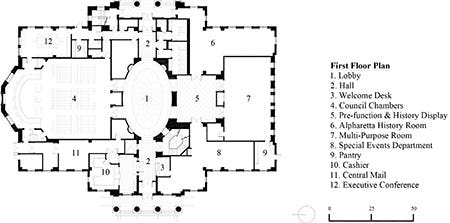

As Swartz explains, the form of Alpharetta City Hall can be viewed as very much derived from the program. “In other words, in a city hall project the client begins by noting, ‘We want these uses on the first floor, and we want these uses on the second floor, and we want all these uses on the third floor.’ Then, as the architect, you try to arrange those requests into a sensible-looking building.”

For example, he says the way the building has a center block with wings coming off of it directly reflects the need for large spaces on the ground floor. “Entering the front door, you pass the greeter’s desk and the cashier’s office (where residents or businesses can pay bills) and then arrive at the central main lobby. Then off of that is the city council chamber – the largest single space within the building. It is on the ground floor not only for ease of access, but also because that’s the one space that’s going to be open late at night.” (Because council meetings can run until midnight or later, it’s inadvisable to have the chamber on an upper floor that allows the public in other parts of the building during off-hours.)

Off of the city council chamber is the conference room where for those meetings of the council can go into executive sessions before, during, and after the public meetings. Across the main lobby from the city council chamber is the multi-purpose room. Since this facility is intended for all different kinds of events, it too needs to be on the main floor. Behind the multi-purpose room is the history room, an exhibit space that tells the history of the city.

“Add in a series of other supporting functions – restrooms, a receiving area, equipment rooms and some miscellaneous office space – and that pretty much rounds out the ground floor program,” says Swartz. “But when you total it all up, the first floor ends up significantly larger than the upper floors. So that’s always one of the challenges: taking these program requirements and adjacencies and figuring out how to make them into a building volume that looks reasonably proportioned.”

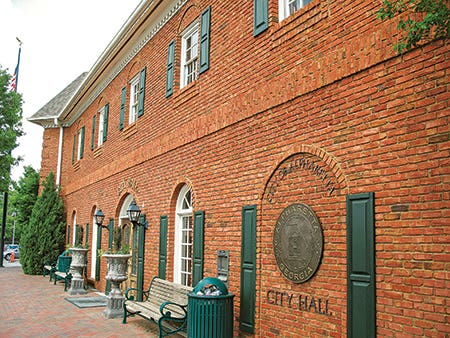

More space and improved, consolidated offices were major goals of the new City Hall, of course, but another essential function was to be a visual and symbolic anchor for the new City Center. “It was important for us to get a full three stories at the center of the building, so that it has a certain level of civic presence,” says Swartz. “We wanted it to have a sense of verticality because we knew it was going to be sitting in this axial position relative to the green, and at the end of the street leading up to it.”

With the bulk of the building’s spaces all wanting to be on the first floor, this sounds like challenge enough to design but even trickier considering the topography. “The grade from the commercial area along Main Street to the City Hall front door actually slopes down eight to nine feet – almost a full story of drop,” says Swartz. “So if you imagine the facade without the third floor, it would be quite short relative to Main Street. Therefore it was critical that we develop that verticality in the middle of the building.” He adds that verticality was less important on the wings, which will not be as visible when the commercial front blocks are developed.

Upper Floors and Higher Offices

Because the council chamber is a two-storey high space, there are no uses directly above it (though a few offices nest around the perimeter). However, since the multi-purpose room is a single story high, it offers second-floor office space that primarily houses the finance department, along with human relations and the IT department. The third floor though has a character and function all its own.

Explains Swartz, “The third floor is distinguished by a series of three arched openings in front that contain pairs of doors that open onto the porch space on the top of the portico.” Behind those three openings is the building’s executive conference room, which accommodates important events and meetings related to the city’s business. It is adjacent to the Mayor’s office, and is also served by an adjoining catering kitchen. “The room overlooks the Town Green and future development sites, thus providing an ideal location to showcase Alpharetta and host events related to such matters as economic development.” The rest of the third floor is more executive offices, such as for the city manager and the assistant city manager.

The design for a building that belongs to the community extends to its siting within the City Center development. Previously, the thought had been that City Hall should be located closer to Main Street amidst the commercial development. After studying numerous layouts for the site that included alternative locations for City Hall, the preferred siting placed the building at the edge of the new city park.

The suggestion was controversial at first – some citizens saw it as an invasion of public greenspace – but the foresight has proved itself. “The building helps to activate and provide a focal point for the park,” explains Swartz, “and the new space created between City Hall and the new library has become a public garden.”

The building has two fronts; the main entrance facing the Town Green, and a second entrance facing into the park. “Each is linked by the entrance-lobby sequence that extends through the building,” he says. Because of the grade changes, the park-side entrance leads to a terrace and a symmetrical arrangement of stairs and landings that connect to a natural clearing in the center of the park where the ground slopes to create an amphitheater for performances.

“The two really enhance each other,” Swartz reflects. “The City Hall sitting at the edge of the park makes the park feel like a special place, and vice-versa. It’s a wonderful setting for both park and building.”

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.