Religious Buildings

The Restoration of St. Patrick’s Cathedral

PROJECT

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, New York, NY

ARCHITECT

Murphy Burnham & Buttrick; New York, NY; Jeffrey Murphy, AIA, LEED AP, partner-in-charge; Rolando Kraeher, AIA, project architect; Jean Phifer, FAIA, stained-glass specialist; Sarah Rosenblatt, preservationist Restoration Consultant

Building Conservation Associates, Inc. (BCA), New York, NY; Raymond Pepi, founder and president; Ricardo Viera, director, BCA Field Services; Christopher Gembinski, co-director, BCA Technical Services

Construction Manager

Structure Tone, New York, NY

Owner’s Representative

Zubatkin Owners Representatives

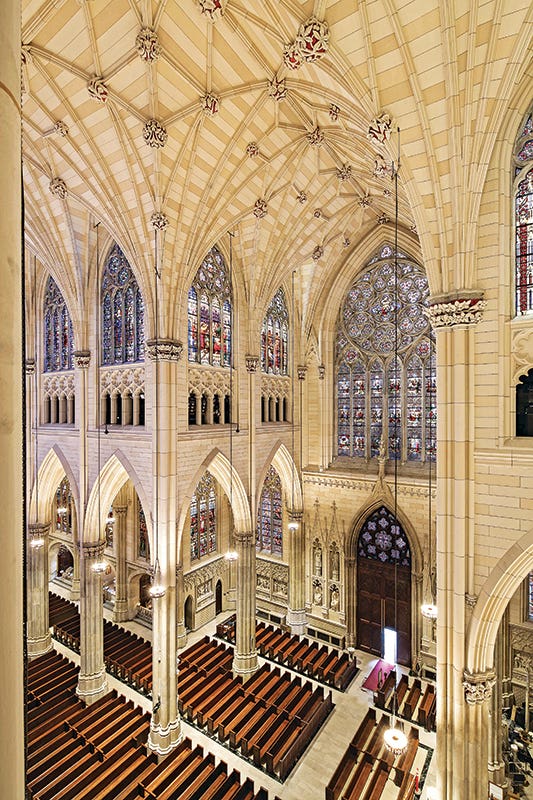

When Pope Francis came to New York City in September, 2015, the city greeted him with warmth and enthusiasm – and with a just-restored and gleaming St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The multi-year, $177-million project addressed a multitude of safety program and building conservation issues for this iconic building that fills a city block on Fifth Ave.

Restoring an Icon

It all started back in the 19th century when a group of immigrants saved their pennies to contribute to a new Gothic Revival cathedral designed by James Renwick, Jr. He was selected in 1852, shortly after he designed Grace Church in downtown Manhattan. Construction stalled during the Civil War, but the first mass was celebrated in 1879, and the cathedral was officially opened to the public in 1888 with the completion of the spires. The Lady Chapel was added in 1906. The magnificent 40,000-sq.ft. cathedral measures 396 ft. 8 in. in overall length with a height of 329 ft. 6 in. from the nave floor to the top of the spires.

The recent restoration project started nine years ago, says Jeffrey Murphy, AIA, LEED AP, partner at Murphy Burnham & Buttrick Architects. “We were asked to do a needs assessment after Cardinal Egan had noticed a crack in a column and staff were finding pieces of stone and mortar on the sidewalk.” Working with Building Conservation Associates, the firm identified a wide range of problems. “In spite of the fact that the building looked incredible, the architecture masked the fact that quite a bit lot of damage on both the interior and exterior existed,” he explains. BCA discovered chunks of stone and mortar that could be pulled off with your hands and areas where the roof was leaking. The plaster on the interior was unstable in certain areas and the HVAC systems were beyond their useful lives.

The needs assessment was completed in 2007, and Murphy Burnham & Buttrick was then asked to design the conservation of the cathedral. The program included scopes of work for the interior and exterior of the cathedral, the rectory, the parish house, the Cardinal’s residence, the stained-glass windows, and a new heating and mechanical plan. “We finished all of the design drawings and were about to start construction when the world financial crises came along in 2008 and put a halt to the work,” Murphy explains. “Work was re-initiated with various life-safety upgrades and the rectory renovation, and then later, in 2011, we got word that we were to move forward with the full conservation project.”

Building Conservation Associates (BCA) was brought in as the Restoration Consultants. “St. Patrick’s Cathedral is unique and quite amazing in many ways,” says Raymond Pepi, founder and president of BCA. “Because the emphasis was on conservation, MBB brought us in to work on the conditions assessment of the building envelope and interior, followed by assisting them with creating technical specifications, drawings and bid documents. We had conservators on site every day during construction for the last three years.”

He points out that “the rationale for the project stemmed from material failure; where isolated areas of plaster and stone had detached from the building. When we say it is a conservation project as opposed to a restoration project, we mean there was no attempt to undo prior repairs of alterations unless they were failing or non-functional,” says Pepi. “The goal was to conserve the existing fabric using state-of-the-art methods.”

The building required 30,000 separate repairs, and 18,000 of those were on the marble exterior which had turned a dingy gray over the years. Most of it is Tuckahoe marble from Westchester, NY, along with Cockeysville marble from Maryland and Lee marble from the Berkshires in Massachusetts. “Because the Tuckahoe marble quarry has been closed for over 75 years, previous campaigns used a significant amount of gray Georgia marble that does not really match the creamy Tuckahoe or Lee. This inspired us to find real Tuckahoe for our repairs, which we did,” Pepi points out.

Repairing the Exterior

“The first job was to clean the marble, using Rotec equipment, which combines water and inert mineral power under very low pressure. It works like an eraser to remove only the soiling without damaging the stone,” Pepi explains. “In addition, previous campaigns had used mortar containing Portland cement, causing the stone arrises (edges) to spall. For this and other reasons, all mortar on the entire building was carefully cut out and replaced with mortar that reproduced the original texture and color and that was physically compatible with the stone.”

“On the exterior, we decided not to undo other work from previous campaigns,” says Pepi. “That would have been an enormous task. For example, in the 1970s they had taken the Tuckahoe marble off the five entries and replaced it with Georgia marble. To put back what was originally there would have been an enormous undoing of work that was actually in good condition. And it represented a period in time. We didn’t feel justified in undoing it.”

“We were much more interested in restoring Renwick’s original outline, so when you look at the building you would see architectural delineation that Renwick had intended,” Pepi says. “But we didn’t put back gargoyles and all the triangular ornamental pieces on the spires. Our goal was to re-establish the parameters of the architectural outline of the building so it could be read as a work of art.”

Brightening Up the Interior

On the interior, extensive repairs were made to the plaster as well as to the stained-glass windows and the historic organ. The interior had also become dark and dingy because of candle soot and pollution which impacted the light in the cathedral because the stained-glass windows had darkened.

While the interior was originally intended to be carved stone, plans changed when the Civil War interrupted construction. Renwick decided to use plaster painted to look like stone, as a money-saving measure. “Renwick wanted to use brick vaults in the ceiling, but they couldn’t afford it so they used plaster, lath and wood to simulate the vaulted ceiling,” says Pepi. “This reduced the weight dramatically, so ultimately flying buttresses were not required to support the building.”

Although the exterior is all real stone, Pepi points out that interior columns are Tuckahoe marble, up to about 35 ft. “The capitals are plaster, and then everything above that is either cast stone or plaster. Renwick used real marble where it mattered and then everything above that was simulated.”

The wood lath was cleaned from above and the plaster re-attached and repaired before it was painted three colors to give it the appearance of stone. Before this work started, a large section was cleaned and painted, to show the congregation and owners how much better it would look.

While the new painted interior contributed to the lightness of the interior, the repair and cleaning of the 75 stained-glass windows also brought more daylight into the cathedral. Murphy explains that the stained glass was in better condition that the design team originally thought. “Of the 3,200 panels, we took out approximately 6% to be repaired,” he says. This work was done by Botti Architectural Arts in its studio in LaPorte, IN. They repaired and cleaned the others onsite.

“We fully cleaned the windows, and replaced glass as needed,” Murphy explains. A venting system was developed by the stained-glass team including Jean Phifer, Drew Anderson (on leave from the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and British stained-glass expert, Keith Barley, to prevent condensation and heat build-up between the protective glazing and the stained glass. This involves undetectable hinged pieces of glass that open outward slightly, to allow air to circulate between the stained glass and the protective glazing.

Restoring and Repairing the Organs

The cathedral’s two organs were also repaired and restored. The larger one has 7,855 pipes ranging in length from 32 ft. ½-in. and a second one has 1,480 pipes. Both were restored by Peragallo Pipe Organ Company.

In addition, the two main bronze entry doors, each weighing 9,200 pounds were restored and rehung by G&L Popian. They removed seven layers of paint and restored the original patina.

A major factor in completing the work in a relatively short time frame – three years – was the use of a software program called BIM360 that stored the entire project in the cloud, allowing all members of the team instant access to it, using ipads in the field and desktop computers in the offices.

“Originally this was scheduled as a five-year project, but the owner requested that we reduce the time frame,” Murphy says. “Having this tool was incredible and helped us shorten the schedule. The alternative, when new work such as a masonry crack was identified, would have been to go back to the office, make a sketch and email it to everyone, and days later the work would be done. With BIM360, we could communicate instantaneously and the work could be initiated right away.”

“This was a big, complicated job,” says Pepi. “Using BIM360 definitely expedited it, but more importantly, it allowed us to maintain the same quality during an accelerated schedule.”

One major part of the restoration is the addition of the geothermal heating and cooling system, now being installed. “We are currently drilling our tenth and final well,” says Murphy. “They are as deep as 2,200 ft. and will deliver 240 tons of air conditioning and the required heating, using one-third less energy than a conventional plant. The wells are deeper than the World Trade Center is tall. We actually had to get a mining permit from the state of New York.”

The system will serve the cathedral, the rectory, the Cardinal’s residence and the parish house, while significantly reducing the amount of carbon emitted into the environment.

“It was a real privilege to work on this building,” says Murphy. “It is an iconic and incredibly loved structure. Everyone wanted the very best for the project. From the beginning, the client recognized what an incredible treasure St. Patrick’s is and the workers, led by Structure Tone, treated the building with reverence and extreme care. It was a happy coincidence that the work was completed in time for Pope Francis’ visit.” TB

Select Suppliers

Structural Engineer: Sillman, New York, NY

Masonry Contractor, stone restoration: Deerpath Construction, Union, NJ

Plaster/Paint/Wood, decorative painting on the interior: Creative Finishes/Ernest Neuman Joint Venture

Wood doors: Stuart Dean

Windows: Jeld-Wen’s Custom Clad Series

Artwork Conservator/Contractor, bronze and copper patination, sculpture conservation, ornamental figurative copper on exterior: G & L Popian, Inc., Yonkers, NY

Copper Roofing: Osman, Ltd., New York, NY

Window Restoration: Prestige Restoration and Maintenance, New York, NY

Stained Glass: Botti Architectural Arts, LaPorte, IN

Pew restoration: The Keck Group, Inc., Middletown, NY

Organ restoration: The Peragallo Pipe Organ Company, Paterson, NJ

Wood carving: Kingswood Historic, Buffalo, NY