Projects

Classic Colonnade

As often happens with historic buildings, one major project begat another while restoring the Bruce C. Bates Colonnade at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York. “For many years, the colonnade had been enclosed with just its original storm panels,” explains Richard N. Osgood, Jr., senior project manager at Bero Architecture PLLC in Rochester. However, upgrading the colonnade into a conditioned space with a large, insulated glazing system also provided the opportunity to rebuild the surrounding structure and return some columns to their original, limestone versions.

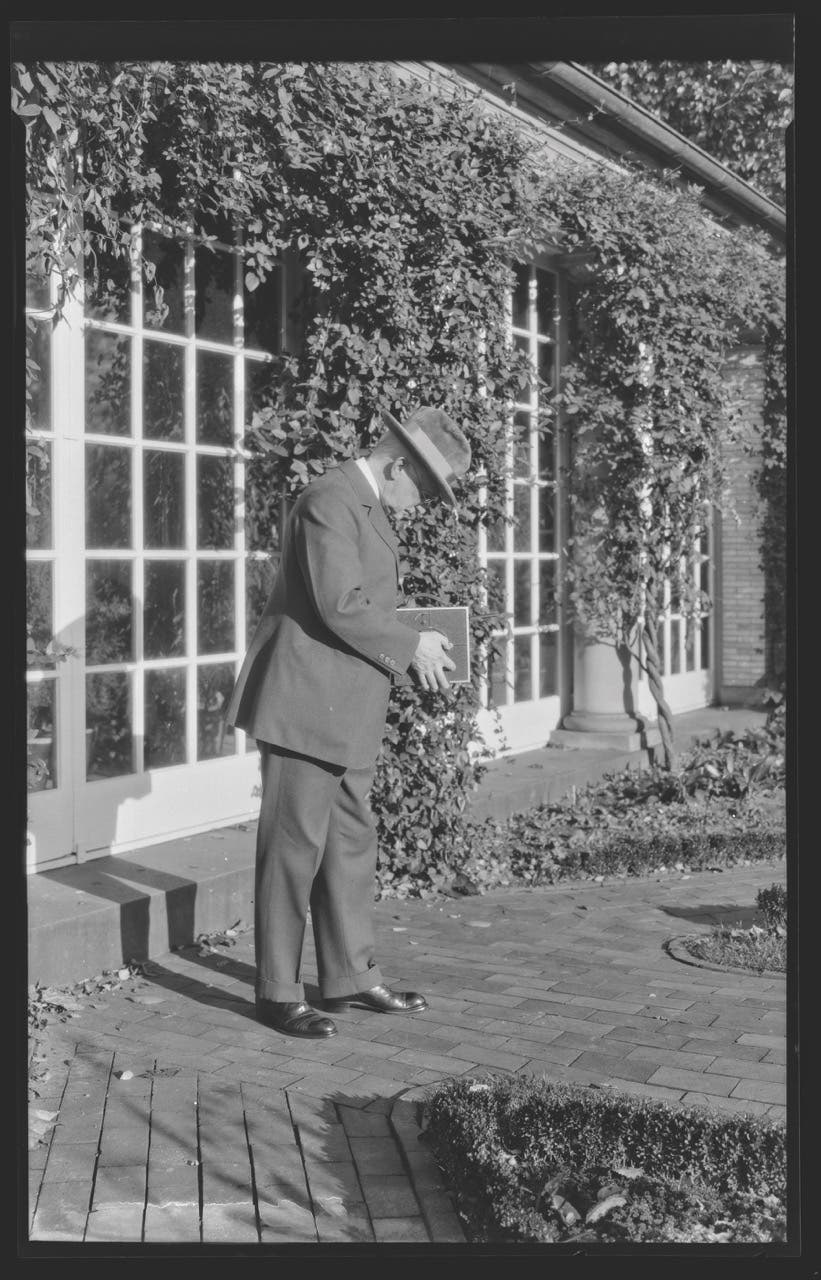

When George Eastman—film pioneer, photography popularizer, and entrepreneur behind the Eastman Kodak empire—built his mansion in 1905, he included an open-air colonnade to showcase his beloved Terrace Garden. Later, Mr. Eastman and his architect, J. Foster Warner, designed a series of multilight storm panels to go in and out seasonally, but subsequent owners, such as the Eastman Kodak Company and the George Eastman Museum, always left the storms up. “The colonnade became a critical circulation path between the mansion and the International Museum of Photography and Film built in 1989,” explains Osgood. “Unfortunately, the storms were poor-fitting, with very little supplemental heat, so the corridor could be frigid in winter, and unbearably greenhouse-hot in summer.” In 2019 the Eastman Museum embarked on replacing the storms with single, wide-open lights that would give the impression of being outdoors.

Not as simple as it sounds. Explains Osgood, “We had to go to Europe to find a manufacturer who could provide large enough insulated glass units, averaging 8 feet, 9 inches wide and over 9 feet tall.” Then, to make the impression convincing, they planned to align the butt ends of those glass panels behind columns to hide the joints. “But to do that, we had to design the support system at the base of the colonnade to hold the panels in place.” He says it was also necessary to engineer a new structural steel head channel—a sort of C shape—to support the glass panels at their tops.

Before work could begin on the glass panel system, however, the architects needed to address conditions on the existing colonnade. The original granite water-table step was in good shape for supporting the new limestone columns, but a ramp in the walkway that changed elevation into the mansion would have to go. More problematic was the reinforced concrete slab of the walkway. “You could see a lot of spalling concrete and exposed rebar,” recalls Osgood, “nearly the length of the walkway underside,” which is actually the ceiling of a service tunnel under the colonnade. “It’s part of an elaborate system,” he explains, “connecting the mansion with the Dryden Theater and over to a garden building and the main steam plant.”

After debating whether to patch the failing materials with fiberglass mesh, the architects decided to replace all of the walkway floor. A good move, it turns out, because the floor construction was poor. “The minute we started jack-hammering, the whole floor literally crumbled on us, revealing charcoal cinders and other junk in the mix,” recalls Osgood. “So we built a whole new ribbed steel deck and poured a concrete slab on top, laying Ludowici quarry floor tile to replicate, as closely as possible, the original walkway tile.”

This rebuild required temporarily supporting existing mechanicals in the tunnel attached under the floor. “We also had to plan for the new HVAC system for the enclosed colonnade to be environmentally comfortable year-round. The new heating system, for example, has elaborate ductwork going up and around in all directions just to access the various areas of the colonnade.”

Repairing deferred maintenance and fire damage became another project. In 1949, a fire completely charred the southern end of the colonnade while the mansion was undergoing conversion into a museum. “Management of the time decided they couldn’t put back stone, so they replaced that section with wood columns.

Adding the glass panel system then became an ideal opportunity to return the 1949 replacement wood columns to limestone. The new 8-foot, 10-inch-tall Tuscan order columns are solid, Indiana limestone shafts with tooled shafts, capitals, and bases. “The original stone columns farther north were all still intact, but needing some minor repairs, so we kept those.”

Back when the colonnade was all open, Mr. Eastman had installed lattice on the brick mansion wall to let ivy climb up inside the vault. “When we took that lattice down, we saw significant cracks where the cross-gable was failing due to undersized and weakened structural members, along with evidence of long-term leaking. So, new rafters were sistered-on in the valley, and a brand-new ridge beam installed to straighten-up the 5-inch sag in the roof.” On top, the colonnade got a brand-new roof deck with waterproof membrane underlayment, Alaskan yellow cedar shingles, and new copper gutters.

Sometimes that additional project, while not pressing, is best done along with current work. For example, the museum’s expected next major expansion renovation is a series of new galleries within the former servants’ areas of the mansion that will explain the story of Mr. Eastman’s life. “So, we closed off an existing entry point from the mansion into the colonnade, dating from the 1948-49 renovations, and cut a new opening in the brick wall, and constructed a new cross vault in the colonnade,” he explains. “This gives the museum a new entry point into Mr. Eastman’s former kitchen and to the galleries that are being designed,” says Osgood. “It’s all about planning for the future.” TB

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.