Public Buildings

Citrus Square’s New Urbanist Master Plan

PROJECT: Citrus Square, Sarasota, FL

ARCHITECT: Jonathan Parks Architect, Sarasota, FL; Jonathan Parks, AIA, principal; Chris Gallagher, project manager

GENERAL CONTRACTOR: Pierce Contracting Inc., Sarasota, FL

A decade ago, the city of Sarasota, FL, adopted a 20-year Downtown Master Plan designed by Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company, one of the leading firms in the New Urbanism movement. The plan, commonly referred to as the “Duany Code,” consisted of major themes such as connecting downtown to the bayfront, implementing a system of walkable streets and encouraging walk-to-town neighborhoods; its overall goal was to reform the automobile-oriented city by creating pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly streets.

Before the Duany Code was finalized, developer Mark Pierce and his partner purchased plots of residential property along what would later become the downtown edge – which qualified for mixed-use projects. By the time the city rezoned the bayfront and downtown area, Pierce owned an entire city block, more than half of two adjacent blocks and controlled several intersections on a primary avenue. For young architect Jonathan Parks, AIA, principal of Sarasota, FL-based Jonathan Parks Architect, the design and construction of Pierce’s development presented a great opportunity to leave a lasting impression.

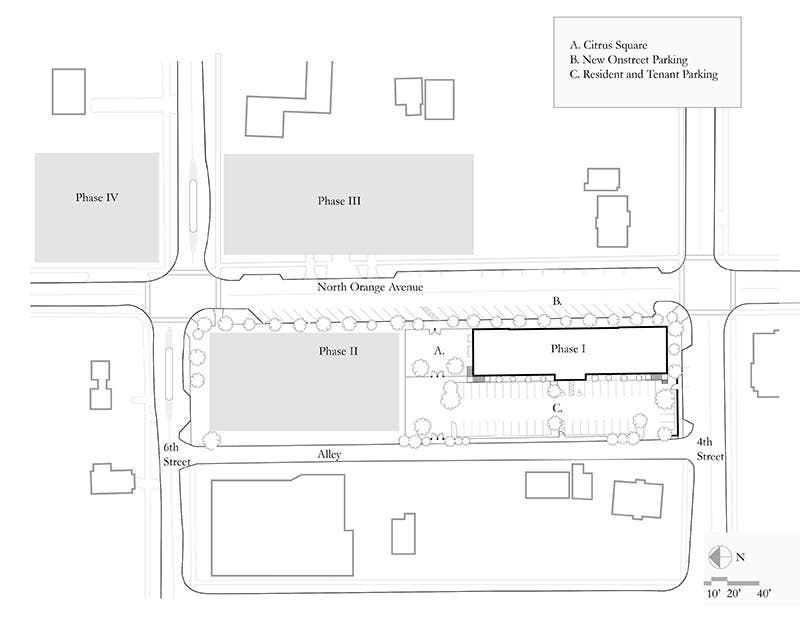

The design of several city blocks was separated into four phases over ten years. The first phase comprised a 35,000-sq.ft. building with boutique retail space on the ground floor and condominiums above.

A Successful Mixed-Use Project

“For this project to be successful it was going to have to compete against a powerhouse in retail experience and that’s the suburban mall,” says Parks. “A suburban mall is basically a big box with parking surrounding it. That has been extremely successful from a developer standpoint but this is an urban project and we had to get all the details right. Programmatically, what we needed to start with was the big picture.”

Parks and his design team, led by project manager and designer Chris Gallagher, examined multiple mixed-use projects but couldn’t find one that was successful from a pedestrian experience. “We saw a couple that were very contemporary and modern in aesthetic but they weren’t something that enhanced the walkability of the street – they lacked scale, detail and material palette,” says Parks. “Our office is known for doing very contemporary work. When we looked at what was successful in mixed-use projects of this scale we had to admit to ourselves that this was going to be a very modern building in terms of how it was built but with a traditional façade, and that was one of the most important gestures we could make.”

Further research involved studying cities such as Venice, Italy, and Nice, France, as well as visits to Barcelona, Spain, and Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. In the U.S., many successful buildings were torn down during the Urban Renewal era so the design team researched movies and photos that depicted turn-of-the-century buildings. They determined that to achieve the proper scale and proportion, the building would have to be three stories – instead of five as permitted by zoning – and the half-block-long elevation should have multiple façades to create the illusion of individual buildings similar to row houses.

What Makes Neighborhoods Attractive

“When we studied traditional neighborhoods and walkability, three stories was the best feel for the street,” says Parks. “The developer also wanted to have the feeling of a turn-of-the-century building where somebody can have a little storefront that they live above. He wanted that live-work relationship that everyone is talking about – the traditional New Urbanism where people are able to live and work in the same area and potentially walk to work.”

A series of six traditionally-styled facades, each with individualized architectural details, suggests that they were built over time. The varied materials and different rooftops, including terra-cotta tiles, cornices and a pediment, create a staggered effect. Large storefront entries of different wood species are accompanied with custom awnings and light fixtures. French doors with cast-stone surrounds, brackets and wood shutters open to small balconies with distinctive undersides.

At the center, the two upper level units feature open-top terraces with wrought-iron railings. A pale color palette of lilac, pink, yellow and natural stone pays homage to the city’s Mediterranean Revival heritage.

The exterior is clad with either cast stone or stucco and all materials were hand-selected from physical samples. “When we developed the details for this building, Chris Gallagher had a very lovely quote,” says Parks, noting that natural materials and authentic details attract pedestrians and enhance the walkable environment. “Chris said, ‘We want to think like a raindrop. How does a raindrop land on the balcony, move to the edge and drip off the edge, and find its way down the fascia without making its way back and staining the building?’ This can’t be done with foam so every single one of the stone pieces was custom designed for its specific location on the building.”

Eating establishments are strategically placed on the north and south ends of the building, while small mom-and-pop shops are placed in between to dictate the pedestrian flow. “Just like in a mall, a big tenant on either end drives traffic in between,” says Parks. “You don’t want people to stay on one side; you want them to walk down the length of the building. It just so happens that people like to eat so we positioned each end with restaurants.”

The existing streetscape was dismal and barren with cracked sidewalks and single-family bungalows. Cars sped down the roadway without traffic lights, crosswalks and parking spaces to provide even remedial traffic calming. “We went to the city and asked them to lower the posted speed limit and to allow us to put landscaping and additional parking right on the street,” says Parks. “We wanted all the parking on the street or in the back and not under the building. We repaved the entire road in both directions and added over 50 new parking spaces. This was key to the success of the lower level retail experience.

“I also promoted the idea that we wouldn’t build on all of the property, to create a square for people to walk to,” says Parks. “The square is on perfectly buildable land. We didn’t build the tallest that we could and we didn’t build on all the land, and that’s pretty rare. The streetscape and pedestrian experience really informed every decision we made. That’s why we created the square that then defined the name of the building.”

In addition to being the first project in Sarasota to adhere to the Duany Code, the development also included many green building technologies. High-efficiency water, plumbing and electrical systems are installed in all units. The doors and windows contain hurricane glass that withstands 140mph winds, LED streetlights are mounted on the sidewalk, low-maintenance plantings are used throughout the landscape and all of the rainwater from the building and parking areas is collected onsite. “When we were designing this building we were far ahead of LEED,” says Parks. “There wasn’t even a checklist for mixed-use projects available at the time.”

The LED streetlights were manufactured by Bradenton, FL-based Beacon Lighting. Other key suppliers included West Des Moines, IA-based Windsor Windows and Doors; Register, GA-based Stewart Brannen Millwork (wood doors); Sarasota, FL-based Mullet’s Aluminum (metal railings); Dallas, TX-based King Architectural Metals (cast aluminum); and Venice, FL-based Jansen Shutters and Specialties, who supplied the custom awnings.

Completed in November of 2009, the success of Citrus Square is the result of a true collaboration between developer and architect. “Mark Pierce wanted the architect to give him 20 great ideas and of them he picked the top ones,” says Parks. “We could have built the project to five stories but we told him that the scale wasn’t right so we only built three. We convinced him to create a true sense of space with a square and got him comfortable with the fact that even though he paid a lot of money for that piece of property we weren’t going to build on it. These are things that are unheard of. Pierce has been a great collaborator. An architect can have a great idea but if the developer or client doesn’t believe in it, it’s never going to happen.”