Public Buildings

Pfeiffer Partners Restores the Historic Atascadero City Hall

PROJECT

Rehabilitation of Atascadero City Hall, Atascadero, CA

ARCHITECT: Pfeiffer Partners Architects, Los Angeles, CA; Stephanie Kingsnorth, AIA, principal

GENERAL CONTRACTOR: Diani Building Corp., Santa Maria, CA.

By Martha McDonald

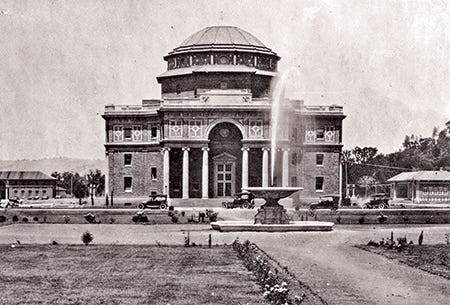

Founded in 1913 as a utopian community by Edward Gardner Lewis, Atascadero, CA, was the first colony west of the Mississippi. To attract people to the area, Lewis commissioned a prominent San Francisco firm, Bliss and Fayville, to design a centerpiece for the new colony. Construction began in 1914 and was completed in 1918.

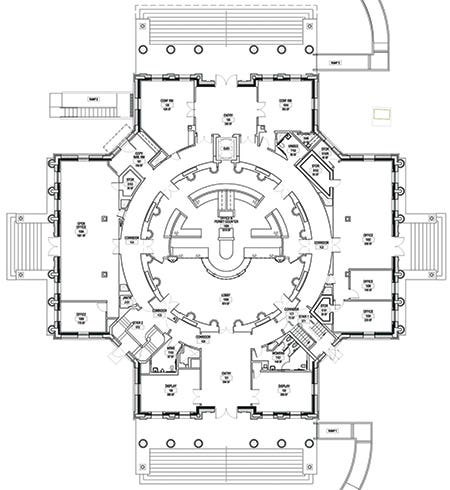

The result was a 58,000-sq.ft., symmetrical four-story structure designed in the shape of a Greek cross. It incorporates two central rotundas; the more ornate one on the ground floor, with a diameter of 56 ft., reaches a height of 40 ft. The upper rotunda is actually a 56-ft. 9-in. wide octagon that is 44 ft. high.

The building served as headquarters for the Colony Holding Corporation until the 1920s when the enterprise went bankrupt. Then came real estate offices, a bank and a number of different schools, including a boys’ boarding school. The County of San Luis Obispo acquired the building in 1950 and used it as a Veteran’s Memorial. Finally in 1952, the county moved its offices into the building. When the City of Atascadero incorporated in 1979, the building became the City Hall.

Along the way, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and was made a California Registered Historical Landmark in 1984. Also in the 1980s, portions of the interior were painted pink and blue for the filming of the movie, My Blue Heaven.

Everything changed when the 6.5 San Simeon earthquake hit central California on December 22, 2003, sending city employees diving for cover as debris fell around them. The damage was so severe that the building was red tagged and had to be abandoned. Pfeiffer Partners Architects was brought in to restore the City Hall under FEMA guidelines, but the project turned out to be much more extensive.

“We had no historical information. Nothing,” says Stephanie Kingsnorth, AIA, principal, Pfeiffer Partners Architects. “We didn’t know the structure. We didn’t know why the damage happened the way it did.” The architects brought in a laser scanning company, As-Built Services, and they were able to create plans and exterior elevations. This, however, didn’t show how the building was constructed. Kingsnorth explains: “We had to crawl every inch to see how it was put together.”

The only other bit of evidence about the building were photos taken during the original construction. These were supplied by the Atascadero Historical Society. This group was formed after Lewis’ death when his house was cleared out and his belongings put out for garbage pick-up. A group of citizens knew this was valuable information, so they saved it. These became the first records of the historical society. Kingsnorth credits the society with providing invaluable, helpful information during the restoration and rehabilitation of the City Hall. “We couldn’t have done it without them.”

What the Pfeiffer team discovered from its research was that the building was actually two structures.

The first through third floors was a concrete frame with exterior masonry walls. Past the third floor, it was basically an unreinforced masonry building, with a very light steel frame.

Also, the boys’ school had added wood-frame structures on the fourth floor. “We found that some of these were sitting on leftover loose pieces of masonry. None of these bizarre construction methodologies were documented anywhere,” Kingsnorth says. “That two-part structure explained why there was so much damage when the earthquake hit. The top twisted in a different direction from the first three floors.”

“This was one of the most complicated projects we have ever worked on,” she notes, adding that funding it was one of the complications. One of the major funding sources was FEMA, which will pay only to get the building back to the condition that it was immediately before the earthquake. They will also provide hazard mitigation funds, which paid for a modest percentage of the cost to upgrade the building seismically.

“In our opinion the building had some inherent faults caused by decades of multiple uses before the earthquake and the city also wanted to do additional work, to bring the building back to its original intent and beauty,” she notes. “So we had to draw it as two separate projects. The first set of drawings was for FEMA repair and hazard mitigation, and the second set of drawings was of additive alternates and upgrades that the city sent out to bid, to make the building better. We had one contractor dealing with two distinct sets of drawings and keeping all of the billings separate.”

Another funding complication arose when the State of California dissolved all City Redevelopment Agencies and reclaimed previously allocated funds in October, 2011. However the California Cultural Heritage Endowment rallied behind the project and supported it with a $2-million matching funds grant. The grant allowed the city to recreate some of the historic elements that had been removed over time, such as the entry doors and transoms and the missing balusters at the top of the building. “These were really big visual elements,” says Kingsnorth.

The reconstruction of the damaged fourth floor where the masonry had started peeling off, was an important part of the project. “We had to deconstruct the entire top of the building down to the mezzanine in the fourth floor, down to the bare bones, and then rebuild it.”

This phase included removing all of the structures that had been added when it was a boys’ school. Only two of the structures were rebuilt, reducing the weight on the building and allowing more light into the rotunda by re-exposing windows that had long been covered. “The team agreed to rebuild anew, instead of repairing horrible construction,” she says.

“Everything on this level is a combination of salvaged material and new. It was reconstructive surgery,” says Kingsnorth. “The masons were amazing. They had to build a whole new masonry wall blending new with old. There were 11 different colors of brick on the exterior, so we had to color match to get the right combination. We did numerous mock-ups.” Pacific Clay was the supplier of the masonry and the work was done by local masons, Boydston Masonry of Atascadero.

The roof was repaired and restored by King’s Roofing of Patterson, CA, using tile supplied by MCA Clay Roof Tile, Corona, CA. They were able to re-use 85% of the existing roof tile, but only 20% of the upper rotunda masonry was salvaged material. The rest of the salvaged masonry was used to repair damage lower on the building where is was more readily apparent to the general public.

As for the balusters on the exterior of the upper rotunda, Kingsnorth explains “it was really an endeavor to get it right. We had no drawings, only photos that showed it from a distance. It was all about the artistry to get it to where it is today.” The new balusters were created by Gladding McBean.

Other improvements to the exterior included replacing the aluminum doors that had been added in the 1970s with new steel doors designed to look like the original doors. These were made by Hope’s Custom Crafted Windows & Doors. In addition, the south entry (the building had four entries, one on each side) was returned as the main entry.

“When we got the project, the front door had moved to the east side of the building for security reasons,” says Kingsnorth. “We said we needed to work to get the entry back to the south side where it was originally. We put in new doors on all four sides, but the east and west doors are for egress only.”

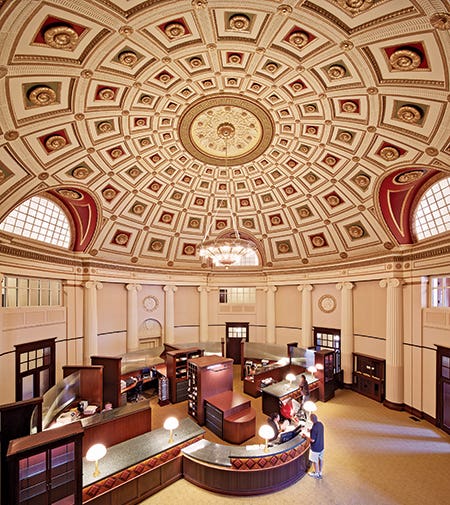

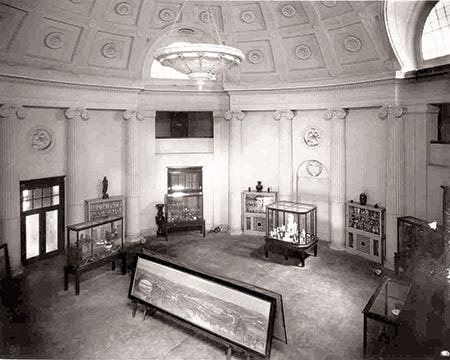

The project also involved significant improvements to upgrade the appearance and functionality of the interior. For example, the lower rotunda, originally designed as a museum to show off the Colony’s agricultural accomplishments, had become a dark, gloomy room over the years. The architects re-opened interior overlooks to bring in natural light and all of the eyebrow windows were made into light boxes. “This made it glow with electric light and natural light,” Kingsnorth points out. “It had been kind of like a tomb. The city was amazed.”

The lower rotunda ceiling, originally white and sparsely painted at the time of the earthquake, was repainted in historically correct colors. “We had no information to guide us, so we developed a scheme and selected historically appropriate colors,” says Kingsnorth. Local painters from Channel Coast Corporation of Santa Barbara, CA, did the work using Frazee paint. In the upper rotunda, the ceiling had been covered in direct-glue acoustic tiles. It was rebuilt using acoustical plaster, returning it to a smooth plaster surface. The original skylight that had long been covered was rebuilt as a light box, enhancing the light in the rotunda.

The decorative plaster in both rotundas and throughout the building was rebuilt and repaired by SLO Plastering of San Luis Obispo. “I can’t speak highly enough of the artisans on this project,” Kingsnorth notes.

Atascadero City Hall is ready to withstand another earthquake.

Not only is the building restored to its former beauty, it’s also much stronger than it used to be. “Almost all of the ‘improvements’ were critical to the repair of the building, not just its upgrade,” says Kingsnorth. “These included the installation of 248 micropiles, new shotcrete on the interior of the exterior walls on floors 1-3 that is now tied to the original masonry using helical anchors, and the installation of FRP (fiber reinforced polymer) on the interior of the rebuilt upper rotunda.”

As for LEED certification, the city opted not to pursue it, but it did work with sustainable elements. “The masonry building itself is sustainable,” says Kingsnorth. “We reused rooftop tile and masonry wherever possible, and everything new meets the energy requirements for the state of California. We also did low-flow fixtures and other elements, but the city was so strapped for funds that they decided not to go through the LEED process.”

The 58,000-sq.ft. historic rehabilitated City Hall reopened in April, 2013. Originally estimated at $35 million, the 10-year project came in at $21.7 million. The building has been brought back to its original intent and is once again the centerpiece of the city. TB