Theaters

The Restoration of Harlem’s Apollo Theater

Project: Apollo Theater Restoration

Restoration Architects: Beyer Blinder Belle, Architects and Planners LLP, New York, NY; Richard Blinder, partner in charge; Christopher Cowan, project architect

Contractor: Barr & Barr, New York, NY

Project Management: Jones Lang LaSalle, CITY

Engineers: Flack + Kurtz, Leslie E. Robertson Associates, New York, NY

In every licensed taxicab in New York, a city map is pasted onto the back of the driver’s seat. In tiny type it shows the locations of the highlights: the Empire State Building, United Nations, Lincoln Center. It’s a truncated and midtown-centric image, with hardly any sites noted above 96 St. In fact, the map cuts off Manhattan altogether around 125 St, which leaves just enough room for a label at the only far uptown attraction that a visitor from just about anywhere has heard of and wants to see: the Apollo Theater.

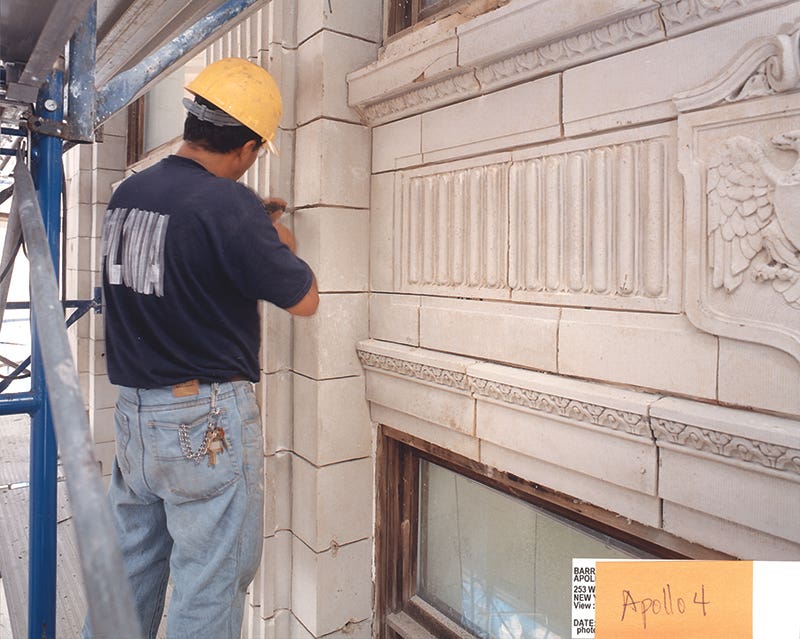

Since last December, tourists have been photographing themselves before a lovingly researched and accurate reconstruction of the Apollo’s Jazz Age façade. The building was scaffolded for years and is still undergoing interior restoration phases. Its gray terra-cotta front is gleaming again, and the place is higher tech and more accessible to crowds than ever before. Restoration teams orchestrated by architects Beyer Blinder Belle have repaired masonry gaps where trees had sprouted, re-combed the terra cotta’s delicate ridges and programmed marquee lights that chase each other. At the façade unveiling, Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced, “There is no icon more closely associated with Harlem’s rich and colorful history than the Apollo Theater.”

Theater History

Practically every black star of jazz, bebop, gospel, disco, funk, soul and comedy has played and maybe even debuted there. The performer roster is a kind of Grammy list, including Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Ray Charles, Eartha Kitt, Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder. Day and night, whether or not it’s showtime, the aspiring stars of tomorrow make pilgrimages to the Apollo to have their pictures taken under the lucky neon.

When the Harlem Theater opened in 1914, only whites were allowed in, and all shows were burlesque. The owners, Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon, had built half a dozen other burlesque houses in the 1910s. They commissioned their new 125 Street branch from Manhattan theater specialist George W. Keister. The architect was known for relatively demure Classical essays, fronted in pilasters and balustrades. On a $600,000 budget for 125 St., he applied anthemia, eagle cartouches, Greek keys, egg-and-dart moldings and Ionic and Tuscan capitals. Keister lined the interior with Adamesque low reliefs of urns, garlands and portrait medallions, all dabbed in gilt.

Dancers frolicked on the stage runway, sometimes raunchily, until new owners took over in the 1930s. As the neighborhood’s burgeoning African-American audiences sought out classier entertainment, Apollo management brought in black singers and musicians. Amateur Night, before famously tough-to-please crowds, has been held on and off since 1933 (Ella Fitzgerald and Gladys Knight are among the steely veterans of that experience).

The Architectural Evolution of the Apollo

Photographers loved the Apollo’s spectacles, so the evolution of its architecture is well-documented. Hurtig and Seamon’s scrollwork signage gave way to more streamlined forms in the 1940s. Helvetica neon letters were set onto a vertical blade trimmed in red, while a horizontal sign atop the marquee blazed with a curvy typeface edged in blue. Keister’s spindly original balustrade, in terra cotta or cast iron, failed and was removed by the 1950s, and a 1980s substitute was cobbled together from turned posts and plywood. The ticket offices started out as two gingerbreaded freestanding kiosks, and then were consolidated into one rounded metal booth.

In the 1960s, the lobby’s pilasters and coffered ceiling were stripped, and brass doors, pink marble wainscoting and crystal chandeliers were installed in the 1980s. The auditorium meanwhile underwent a dizzying series of changes. Floral or nymph murals segued to uniform white paint, which in turn was replaced by red fabric on furring strips. On the seat rows, assorted renovations left behind eight different end standards, either ribbed or filigreed or embossed.

In 1991, the deteriorating and nearly bankrupt house was taken over by a nonprofit called the Apollo Theater Foundation. The staff has steadily fundraised while imposing much design cohesion. The facility remained open through Beyer Blinder Belle’s overhaul, funded by government and private grants and led by partner Richard Blinder and project architect Christopher Cowan.

Examining the Scope of the Project

Defacements have been undone from sidewalk to parapet. The firm matched Keister’s limestone and granite pilaster bases, which stucco and signage layers had destroyed. The stonework frames a steel ticket booth at ADA-compliant height, stainless steel doors and dove-gray terrazzo flooring inlaid with zinc moderne letters modeled after the 1940s neon. The vintage marquee and signage were sagging and hopelessly rusted, so the project team devised replicas updated with code-compliant reinforced armatures and easy-to-change LED and LCD panels. On the marquee’s underside, clear lightbulbs flash in a chasing pattern: four on, one off, luring viewers inside. The architects, with input from sign contractor North Shore Neon, of Deer Park, NY, based the bulb zigzags on original settings found in a broken light controller. “In a project like this,” Cowan notes, “you discover the most amazing archaeological artifacts.”

Upon close examination, the restorers found that the façade’s upper stories were held together mainly by inertia. The ridged terra cotta had been painted and partly gilded in the 1980s, and behind the paint, Cowan says, “there were holes and cracks, and all the mortar had powdered out.” Gladding, McBean, of Lincoln, CA, provided replacements for pieces beyond repair. On salvageable but chipped or unglazed areas, Polonia Architectural Restoration, with advice from Integrated Conservation Resources, applied Keim and Edison Coatings products to reinstitute original finishes in combed, stippled textures and 18 shades of gray. Along a new standing-seam metal roof, a GFRC balustrade, with wider balusters than Keister planned, now conceals a top-floor recording studio added in the 1980s. At the brick rear elevation, repaired fire escapes trail down newly repointed joints to ADA entry ramps.

Beyer Blinder Belle has finished some major interior work as well. Not much is visible to audiences, except for 1,483 new red-upholstered seats with curved, ribbed end standards modeled after 1940s precedents. Aisle lights have been discreetly inserted, and new wire troughs course below fresh red carpeting. This summer, the stage apron is slated to lose its circa-1998 protruding side platforms. The Green Room below the stage will be renovated and ADA-compliant dressing rooms will be added. Clamped-on lights and speakers will be cleared from the stage and side boxes.

“We finish about a phase a year, always doing more as the Apollo gets funding,” Cowan says. “The assignments are always changing, and always interesting.” He’s standing below the marquee as he speaks, and as he finishes the thought, a school group finishing a tour pours excitedly out of the steel doors. A busload of senior citizens has pulled up, and they’re getting ready to disembark. A foreign tourist taps the architect on the sleeve: will he take their picture, underneath the new neon?