Theaters

After the Flood: Restoring the Paramount Theatre in Cedar Rapids, IA

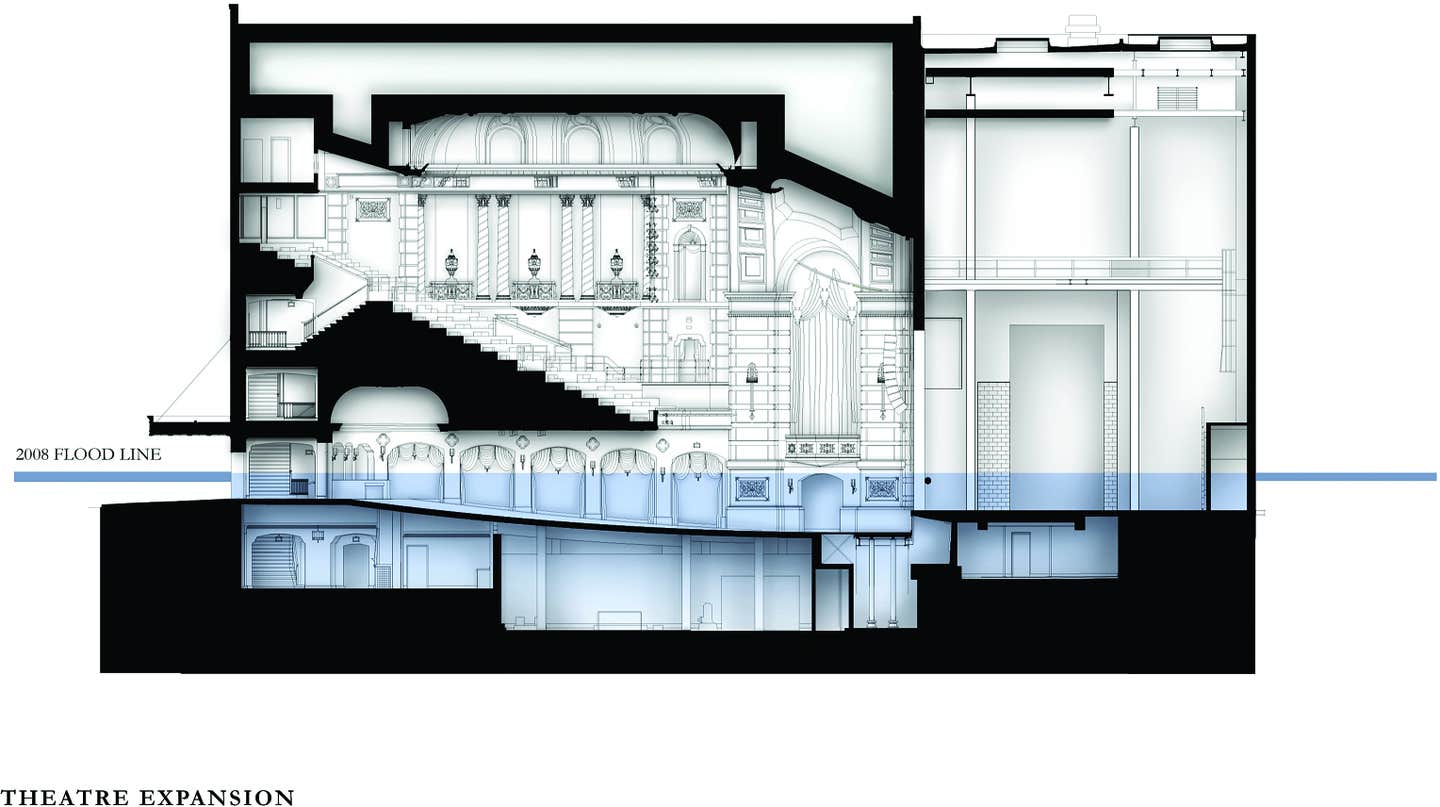

When a disastrous flood hit Cedar Rapids, IA, in 2008, it left the downtown area, including the historic Paramount Theatre, under water. “There was an unprecedented flood. Some called it a 2,500-year flood,” says Tom Johnson, AIA, partner, Martinez + Johnson. “A lot of the downtown was under water, including the theater. There was up to eight feet of water on the first floor, and of course, the basement was under water.”

Listed on the National Registry of Historic Places, the Paramount Theatre has a long history and is one of only about 300 historic movie palaces left in the country. It originally opened on September 1, 1928 as the Capitol Theatre. Paramount Studios purchased it and renamed it the Paramount Theatre in 1929. After many years, it was given to the city of Cedar Rapids in 1975, and shortly thereafter, a $400,000 renovation returned it to its original state.

Another renovation was completed in 2003. Costing $7.8-million, it involved the addition of a 57-ft. wing, new HVAC, restrooms, carpet and seat coverings, plaster work repair, electrical and fire system updates and the addition of the Guaranty Bank Reception Hall.

Then, just a few years later, the devastating flood of 2008 wiped out all of that work.

The city brought in OPN Architects, of Cedar Rapids, a firm that was also working on a number of other buildings in the area, to save the Paramount Theatre. They, in turn, called in Martinez + Johnson Architects of Washington, DC, specialists in historic theaters, to work with them.

“We do quite a bit of partnerships with different firms,” says Bradd Brown, principal-in-charge, OPN. “We do all types of architecture, including higher education, libraries and hospitality. We cover the Midwest but we don’t specialize in a project type. For the Paramount Theatre, we wanted to form a team that could restore the theater back to its original condition, and at the same time, create a theater that could perform better than before the flood. We reached out to Martinez + Johnson because they had expertise in historic theaters. We collaborated on the project from beginning to end. It was a good partnership.”

“We have probably done 30 or 40 historic theaters around the country,” says Johnson. “In this one, the main user was the symphony. We were trying to create a concert hall in a 1928 movie palace.”

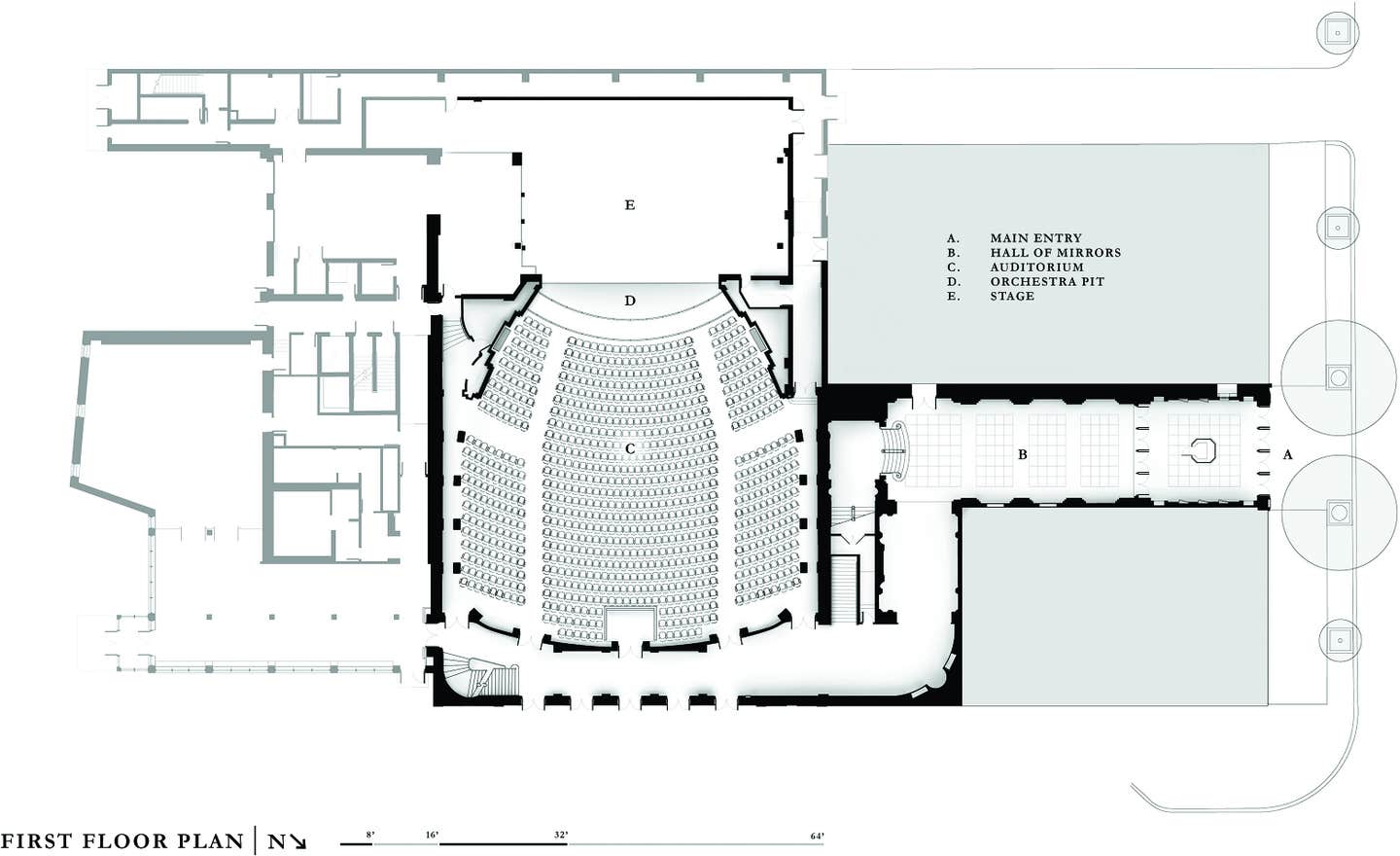

While the interior of the theater was extensively damaged by water and debris, the structure itself was sound. “The challenge was to make the theater perform better that it had before the flood,” says Brown. “It was designed as a silent movie house; it was not designed for larger shows and events, such as touring Broadway shows. To make it more successful, we vacated the alley behind the building and made the stage 20 ft. deeper. We also cleared out clutter to create wing space for the stage. Now the theater can bring in larger shows, and there’s more room for the symphony.”

One major challenge, Brown notes, was meeting FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) requirements. “Since it is a publicly owned building, the Paramount Theatre had to go through the FEMA process. This added a layer of requirements not typical to a building project. It necessitated a number of flood mitigation strategies.”

One of these requirements was moving everything – including all mechanicals – out of the basement. The mechanicals are now housed in an addition built on top of an adjacent building. The performers’ dressing rooms were also moved out of the basement and are now on the second floor. The lower level now provides an additional lounge with bar service and restrooms.

Other improvements to the 80,000-sq.ft. theater included wider, more comfortable seating with more knee room, improved acoustics (Threshold Acoustics of Chicago, IL, was the consultant) and improved performance area and equipment. Theater designer Shuler Shook, of Minneapolis, MN, was the consultant.

In addition, the chandeliers and other historic lighting fixtures were removed and restored by St. Louis, MO-based St. Louis Antique Lighting Co., using energy-saving LED fixtures whenever possible. The theater’s iconic Wurlitzer organ was also saved and restored, under the direction of JL Weiler Consultants of Chicago. The case was destroyed in the flood, but the hidden valves, pipes and bellows could be removed and restored. A national search turned up parts to replace those that were lost.

One of the most visible parts of the project was the restoration and re-creation of the interior historic finishes, including plaster work and decorative painting. Most were damaged or lost. The goal was to restore the historic theater to its original conditions, following the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards.

Johnson notes that initially there was a movement to take out more of the historic material because of a fear that it was molded. “But we were able to remediate the mold and save some of the original materials,” he says. “At first we had to wear hazardous suits and we were on respirators. I’m sure people must have been concerned when they saw us walking down the street in those suits.”

Once the mold was remediated, work began on restoring the historic interior of the theater.

Ornamental plaster was repaired and reproduced by Olympic Companies, Minneapolis, MN, based on historic photos, and other historic investigation. Conrad Schmitt Studios, of New Berlin, WI, was the decorative arts and decorative painting contractor.

“The theater needed extensive repair and renovation,” says Kevin Grabowski, national projects director, Conrad Schmitt Studios. The firm first did exposures and samplings to determine what had been there originally and to show others what to expect.

The complex, intricate decorative painting work included multiple glazing finishes, gilding, marbleizing, trompe l’oeil, and also scagliola-finished columns in the Hall of Mirrors lobby. “It was a very complicated, large-scale project,” he adds. “We had at least 10 people on site at one point.”

Grabowski points out that the primary challenge was the requirement for a quick turnaround. “We had a very tight schedule,” he says. “The symphony was scheduled a year in advance and the theater had to be ready. There was so much other work going on at the same time – flooring, carpeting, seats, electrical – and we all had to work simultaneously to meet the deadline.”

“It wouldn’t have been that difficult if it was just us painting, but we were working with all of the other contractors,” he adds. “There were coordination issues. For example, we might complete some plaster work and then they would want to cut holes for sprinklers. Or we might be working on the ceiling while sparks from welding would be flying.”

The restored historic Paramount Theatre – a $32-million project – reopened in 2012, on time and ready for the symphony’s appearance. The entire project took only 4½ years, about half the normal time for the restoration of a historic theater, according to Johnson. “I cannot overstate Ryan’s value to the project, especially the efforts of John Ryan, the project manager, and of Steve Chia, the site person who took a particular interest in the preservation strategies. Jim Kramer was also instrumental, start to finish,” he adds.

The project has received a number of accolades, including a 2013 Honor Award from the Iowa Chapter of the AIA; a 2013 Silver Award, 30th Annual Reconstruction Awards, from Building Design + Construction; and a 2014 Project of the Year Award from the American Public Works Association.

“The building looks beautiful, and it brings a lot of life to the downtown,” says Brown. “There are a lot of hidden gestures that the patron doesn’t see. These make the theater much more successful so it performs better, like a state-of-the-art auditorium.”

PROJECT: Restoration of Paramount Theatre, Cedar Rapids, IA

ARCHITECTS: OPN Architects, Cedar Rapids, IA; Bradd Brown, AIA, LEED AP, principal-in-charge; Martinez + Johnson Architecture, Washington, DC, Tom Johnson, AIA, partner

CONSTRUCTION MANAGER: The Ryan Companies,Cedar Rapids, IA