Public Buildings

A New Chapter for the Ames Free Library

PROJECT

Ames Free Library, North Easton, MA

ARCHITECT

James Thomas Architect, North Easton, MA; James Thomas, AIA, principal

By Martha McDonald

It all started in 1803 when Oliver Ames, an iron worker, moved to North Easton, MA, and started the Ames Shovel Company. His shovels were used for building the railroads that opened the West, making his family quite successful.

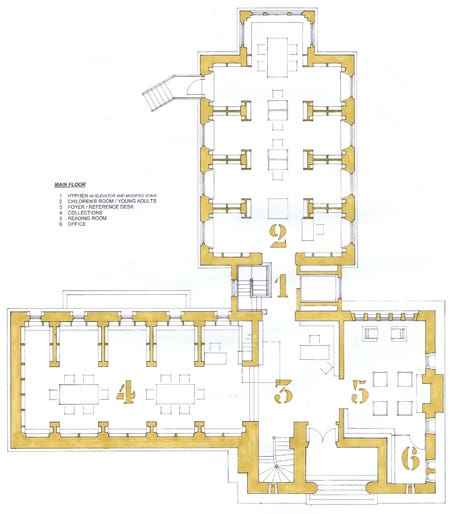

Frederick Lothrop Ames, son of Oliver Ames II, went to Harvard, met H.H. Richardson and commissioned him to design the Ames Free Library (built 1877-79) in North Easton, MA. The 4,350-sq.ft. stone building features an arched entrance facing the street, with a tower connecting the entry to the main portion of the building. Inside are two elegant reading rooms connected by a hall. The smaller one, known as the mantel room, has a massive mantel designed by Stanford White, who was in Richardson's office at the time, and carved by Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

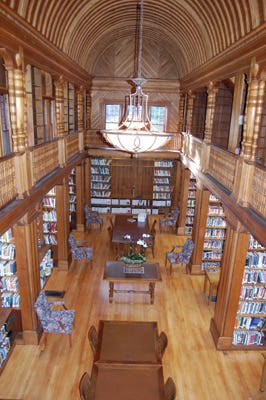

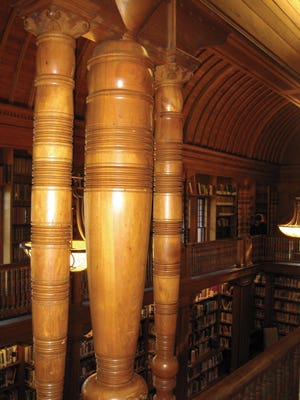

The larger rectangular reading room is replete with wood (butternut, a light walnut that is very rare these days) details, also thought to have been designed by White. It is lined with books to the barrel-vault ceiling and features balcony access to the higher shelves and large windows on the end wall.

The Ames family was so pleased with Richardson's work that it decided to have him design the nearby Oaks Ames Memorial Hall, (1879-81) which was given to the town for whatever purpose they might want. It is now a function hall. Altogether there are five Richardson buildings in North Easton. The other three are: the Ames Gate Lodge designed in 1880-81 for Frederick Lothrop Ames, the 1881 Old Colony Railroad Station, also commissioned by Frederick Lothrop Ames, and the F.L. Ames Gardener's Cottage (1884-85). These five comprise the H.H. Richardson Historic District in North Easton, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

In 1931 Mrs. Fanny Holt Ames donated an addition to the library directing that it be known as the William Hadwen Ames Memorial Room in memory of her husband for the use and benefit of children. The new brick addition by Coolidge Shepley Bulfinch and Abbott added 1,200 sq.ft. to the existing building, bringing the usable space to 5,550 sq.ft.

In the mid-1980s, the town opened another branch and decided once again to enlarge the original building. This project has taken many twists and turns over the years, starting with a study done by Tappé Associates. Then Robert Venturi of Venturi Scott Brown and Associates created a plan for the library involving a contemporary addition, but the town rejected it. Finally, the firm of Schwartz Silver Architects of Boston designed an underground scheme in the mid-1990s, which was widely publicized. This was in the courts for 10 years, and by the time it was settled, the town couldn't afford to build it.

Fast forward to 2006, and James Thomas, an architect who was on the library board, was asked to take on the project. The program called for the creation of more usable space and a general restoration of the historic building. The client was the Ames Free Library, Inc., Donna Richman, president, Board of Directors, and another Ames family member, William Ames, chairman, Building and Endowment committee.

Thomas was born and raised in North Easton and had spent many childhood hours in the Children's Collection housed in the 1931 addition. He had been with Ganteaume & McMullen of Boston, as partner and principal in charge of design for many years, and had moved back to North Easton to start his own practice in 2005.

Thomas increased the usable space in the library by about one-third (adding 3,500 sq.ft.) by clearing out the dungeon-like cellar on the ground floor and replacing and relocating the boiler. The circulation desk, the fiction collection and the new main entry were moved to the new lower level. The new entry allows access from the parking lot (a permeable brick walkway made of Aqua-Brick from Ideal Co. of Westford, MA, was installed) and also creates handicap accessibility. "The relocation of the fiction collection allowed us to liberate the historic barrel-vault room upstairs," says Thomas. "The fiction stacks had been in that room for many years, filling up the center of the room."

"A library restoration is problematic because it's full of books," says Thomas.

In a demonstration of the town's interest and support of the project, hundreds of volunteers participated in a book brigade organized by the library. They moved the collection to an unused historic space about a quarter of a mile away where they operated a temporary library and then held another brigade to return the collection.

To keep the character of the building, Thomas retained most of the masonry in the cellar. "The foundation is left exposed," he says. "We re-pointed it and cleaned it, but it is as originally built." In addition, a former coal chute provides a view into the shelves. The flooring of the new level is bluestone and concrete. A new small mechanical room with a compact gas-fired boiler is now located on the ground floor, tucked away under the main reading room.

Also visible in the new circulation room is the original green granite that was excavated right on the site and used to build the library. "It is the major part of the interior finish of the new circulation room," says Thomas.

Another change that Thomas made was the addition of an elevator from the new ground floor up to the main floor. It is tucked into the hyphen that connects the original Richardson Library to the 1931 addition and has a glass wall providing a view of the outdoors. The other walls are papered with the Bibliotheque bookshelf pattern from Brunschwig & Fils. The original Richardson walls, which had been buried when the addition was built, are now visible to visitors as they step out of the elevator.

The work included both the exterior and the interior. On the exterior, most of the masonry was restored. Richardson's tower was removed piece by piece and laid out on the lawn and reconstructed. This masonry restoration was done by Folan Waterproofing and Construction Co. of South Easton, MA, and the Joseph Gnazzo Company of Vernon, CT.

Crocker Architectural of North Oxford, MA, supplied the copper roof for the new elevator and also restored the gutters and downspouts. The general contractor for the library project was A.P. Whitaker and Sons of West Bridgewater, MA. MEP+FP engineering was supplied by Building Engineering Resources (BER), and the structural engineer was Danker Structural Consulting.

Thomas' work is perhaps most visible in the restoration of elegant Richardson main floor which houses the barrel-vault reading room and a smaller room known as the mantel room. The larger barrel-vault room is the one that was "liberated" by moving the fiction collection to the ground floor. "There is speculation that Stanford White, who was in the Richardson office at the time, designed the reading room," he says. The balcony provides access to the higher stacks and is accessible only to staff. "The elegant railings and columns are original but the railings are lower than today's code which restricts public access," Thomas notes.

With guidance from historic photos, Thomas returned the room to its original appearance, with two original Richardson chairs and tables restored to their place in the center of the barrel-vault reading room. Lighting was also important. All fluorescent lighting was removed in all three rooms on the main floor, and hidden lighting was added. Historic pendants that Thomas discovered in a salvage yard were installed – two to the barrel-vault room, three in the children's room and one to the mantel room. "We would have liked to replicate the original gas fixtures, but it was too expensive," Thomas explains.

In a nod to the current needs, the far wall of the barrel-vault room holds a giant TV hidden behind a wooden screen. The TV can be turned on to look like a fireplace. Also new are a state-of-the-art fire system and a wheelchair lift that takes people up the three stairs from the hall into the reading room.

In the smaller reading room, the mantel room, the massive carved-masonry mantel (designed by Stanford White and carved by Augustus Saint-Gaudens) was cleaned, removing 100 years of grime, and restored. Providing guidance here and throughout the project was Jessica Zullinger, a conservator with Building Conservation Associates New England of Dedham, MA. Another factor contributing to the success of the restoration was the Community Preservation Act in Massachusetts (CPA), a state program promoting historic preservation. It has made a grant for the garden restoration.

The 1931 addition housing the children's wing didn't require as much restoration. The stucco walls were cleaned, and wood flooring found under the cork was exposed and restored. "This wing required only cleaning up and new lighting," says Thomas. The ceiling had had fluorescent lighting from the 1950s. Now these recesses supply the heating and air conditioning to the wing and the room is lit with the three pendants.

Windows and doors throughout were restored by Westmill Preservation, Halifax, MA, and some of this work is still in progress.

As for the future, plans call for the restoration of the main entrance facing the street and re-creation of the formal garden in the grounds behind the building. "We want to create a public space for the town and to add a bocce court," says Thomas.

Since the grand opening in December, 2009, the circulation at the library has doubled. "We get an average of 500 visitors a day," Thomas says. He was able to increase the usable space and to restore the historic rooms while keeping the existing footprint, and he came in on budget - $2.5 million. "I am not a preservation architect by trade," says Thomas. "But I am a pragmatist and I was trusted by the board. We were very careful not to remove any history, and all of the additions and changes are reversible."

Sounds like preservationist to me. TB