Features

Trades Education in the New Century

Where do you go to learn the trades needed to preserve historic buildings? Various schools and programs around the country offer hands-on training.

Since the 1960s, the preservation movement has made gigantic strides in creating a workforce to care for historic structures – historians, architects, planners, government agencies – everything it seems except people to actually do hands-on work, in a traditional and sensitive manner, on the fabric of the historic buildings themselves. Back in 2003, Traditional Building cited just four significant courses of study aimed at the historic building trades. In 2011, when this writer reviewed the landscape, we could push the number to 11 of varying ilks – an improvement, but minimal for a country the size of the United States. Today the head count has dropped to nine with some new names, thankfully, but not enough to even replace programs that succumbed not so much to poor enrollment, but lack of support and recognition.

How can this be? While interest in buildings a half-century and older may be difficult to gauge, their growing numbers – estimated to soon reach half the national building stock – is not. “I think we’re starting to see that public awareness is where the real problem is,” offers Rudy Christian, past executive director of the Preservation Trades Network. “The feeder network for students that need to be in these schools and programs just doesn’t exist yet.”

With the shop and home economics classes of yore long gone, he notes that many students graduate from high school with little exposure to hands-on careers or activities of any kind. This might seem natural for the high-tech 21st century, until you read below how many preservation programs attract adult students who seek the experience with traditional building materials and construction methods they find missing in their education – and more satisfying. Building the “feeder network” Christian describes is not going to happen overnight, but spreading the word about the following programs – or telling Traditional Building about any that should be added to the list – will help.

Belmont College, St. Clairsville, OH

Offering an Associate of Applied Science (AAS) in Building Preservation/Restoration since 1989, Belmont College is among the longest-running programs of its kind. Repurposing the facilities of a mining program that followed the decline of local rust-belt industries, Belmont’s BP/R program has continued to grow to a current enrollment of about 33 students. “A lot of people pursue the preservation trades as a kind of second career,” says David R. Mertz, program coordinator. “They don’t want to sit behind a desk anymore, or they’ve got a four-year degree in history, and they come to us to get the technical side.”

The Belmont program seeks to give students a broad understanding of historic buildings, in part so they can find where their interests lie. “We see trades training basically as a three-prong effort: 1) the academic side – classroom work studying, say, wood species or how materials deteriorate; 2) the technical side – learning a hands-on skill or technique; and 3) the experiential side – where students go out and get a job working for somebody who is an expert.”

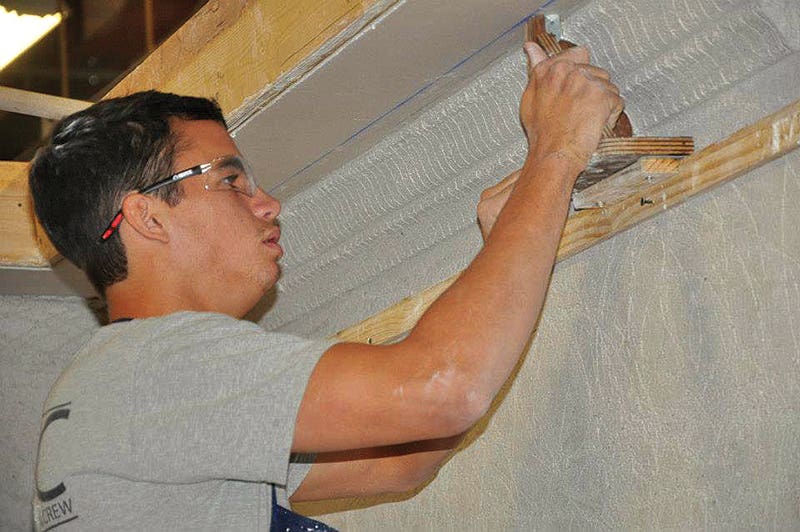

Students are required to complete three field labs, often at a historic house about 10 minutes from the campus. “It’s a workshop, a lab – not a linear construction project,” says Mertz. A typical lab class might be flat-plastering a room or rebuilding a brick wall. “The goal is not to get the house done, it’s to have every student experience a wide variety of processes and activities, to take something from beginning to end.”

New to the program are community field labs, intensive two-week classes that are just like a contracting job. “We take on projects at government or non-profit properties – sometimes on a national level, sometimes regional, and sometimes local.” Recent field labs include re-roofing the spring house at Stratford Hall Plantation in Virginia, and restoring two decorative windows at the historic sheriff’s residence in St. Clairsville. Here students not only learned to bend wood into the teardrop shapes of the window grid, but researched the historic processes, from kerfing to steaming – all beyond a building budget limited to new windows. Says Mertz, “We try to do projects that help with larger goals too.”

North Bennet Street School, Boston, MA

As unique as it is pioneering, the Preservation Carpentry program at North Bennet Street School continues to thrive at one of the oldest (1885) craft and trade schools in America. Begun in 1987 as an addition to long-running NBSS courses, such as furniture- and cabinet-making, piano technology and bookbinding, the Preservation Carpentry curriculum combines, according to literature, an introduction to contemporary residential construction with a thorough grounding in pre-20th century New England house construction.

“It’s a two-year program that enrolls 13 students each semester,” explains Nancy Jenner, Director of Communications and Strategic Partnerships. “Each student has a dedicated bench and works on projects both independently and as a team. Students work both in the shop and on-site.”

While students are encouraged to seek work experience during the summer between terms, each academic year includes fieldwork, typically in collaboration with historical sites and non-profit museums. “One amazing project the program worked on over the past few years is the restoration of the First Parish Church of Dorchester, including the steeple lantern and the windows,” says Jenner. Another is the rehabilitation of the 1753 Hatch Mill in Marshfield, MA, where the first-year preservation carpentry class worked on one of the last water-powered up-and-down sawmills in the United States.

The program is designed to “challenge students at all levels, from the novice with little hands-on experience to advanced students” and typically includes women as well as men. Graduates receive a certificate and seek work in diverse organizations, from custom millwork companies and private contractors to non-profit museums and the National Park Service.

Jenner notes that while the program itself hasn’t changed since 2011, the location has. “In 2013 the school moved from its historic home to a new site five blocks away (the former city printing plant and area police station) with space for the entire school.”

American College of the Building Arts, Charleston, SC

Another unique school that continues to gain traction is the American College of the Building Arts (ACBA), the only such program of study to date to offer both two-year AAS and four-year Bachelors degrees in hands-on trades. Created in the wake of Hurricane Hugo, which in 1989 left Charleston swamped with damaged buildings but short of repair craftspeople, the school graduated its first Bachelors class in 2004. “I think what distinguishes us from some schools is that we don’t require students to focus just on historic preservation or just on new construction,” explains Elizabeth Vice, Director of Institutional Advancement, “we require that they focus on both.”

Across all four classes of the school, enrollment stands at about 37 full-time students, but with plans to reach 250. “Our oldest freshman a couple of years ago was 42; this year the youngest is 17,” notes Vice, “and we are about one-quarter female, the result of a push to enroll more women and minorities.” For each degree, students must complete the necessary credit hours in general education coursework as well as in one of the Craft Specializations: Architectural Stone, Carpentry, Forged Architectural Iron, Masonry, Plaster, and Timber Framing.

“On the liberal arts side, we’re known for our small class size and making sure that every subject we teach ties back in some way to the history and function of architecture and materials,” says Vice, who notes that this spring, the school will begin work on its new home, a historic former trolley barn acquired in part through a donation from the city.

Eight-week internships with actual businesses are required. “Students learn skills and how to work with a team towards real deadlines and real expectations – not just in a collegial environment,” says Vice. She adds that one of the program’s goals is for students to go out and get real jobs, so classes are involved in a lot of projects off-campus, going out and bidding jobs then performing the work.

Careers after graduation are as varied as the students themselves. “Right now, we have two recent graduates who are doing interpretation at Colonial Williamsburg, which is a pretty good market for students who don’t want to, say, go into business.”

Savannah Technical College, Savannah, GA

In October 2014, Savannah Technical College brought its Historic Preservation and Restoration Program under the roof of the newly founded Center for Traditional Craft. “The center includes not only the two-year Historic Preservation program,” says Stephen Hartley, Department Head of Historic Preservation, “but also involves a lot more in terms of research and writing about traditional craft.”

There will also be short courses called the Historic Homeowner’s Academy for people interested in continuing education about historic buildings. “It’s a new initiative to expand the school’s reach,” he says, “and to engage the community better in understanding craft.” Scheduled for 2016, the Academy is designed for owners and residents of historic properties as a way to introduce them to proper repair techniques as well as the processes of design review and applying for historic tax incentives.

Popular even before it expanded to an AAS degree in 2009, Historic Preservation and Restoration is a generalist program, according to Hartley. “All students have to take all the different trades, but our strong points are metalworking, plaster and stained glass. We also offer classes in masonry and carpentry and related skills.”

He says the current enrollment, which is both part-time and full-time, is running about 35 students. The school also offers a Historic Preservation Diploma and a Historic Preservation Technician program for those who want to enter the preservation workforce as either contractors or apprentice workers. “We’ve found that people want to engage with these materials and learn these crafts,” he says, “so we’re starting to get a lot more students that already have degrees – whether in preservation or not.”

To complement their classroom and laboratory education, students also work on actual historic sites. “We collaborate with certified non-profits, so if one needs our assistance, we’ll help with the understanding that the non-profit provides the materials, and we provide the labor at no cost.” Repairing plaster at Green Meldrum National Historic Landmark is a recent project. “We concentrate on deferred maintenance,” says Hartley, “so as not to take away jobs from the contractors that are going to hire our graduates when we’re done.”

Clatsop Community College, Astoria, OR

Slipping under our radar in 2011, the Historic Preservation program Clatsop Community College is nonetheless relatively recent, beginning in 2009. “We’re in one of the oldest cities west of the Rockies, dating from the fur trading post set up by John Jacob Astor’s men in 1811,” explains Lucien Swerdloff, coordinator and faculty, who helped originate the program, “so we have a fairly large inventory of buildings from the 1880s on, and a really strong culture of historic preservation in the region.”

Swerdloff explains that while community colleges typically draw a diverse mix of students, at Clatsop it’s even broader. “Our age range is currently from about 20 to 60; we’ve had students as young as 18 and as senior as 70 – and from all different backgrounds.” There’s the familiar mix of folks who have already worked in traditional construction and related fields such as design, or are seeking a career change. “A fair group are old-house owners who want to learn skills to work on their properties.” Enrollment is currently about 18 students, “a number we’re happy with because we always intended the program to be small,” he says.

Clatsop offers a two-year AAS degree in Historic Preservation, and a one-year certificate. “We have three basic course categories,” says Swerdloff, “general college education requirements (writing, mathematics, etc.), history/theory courses, and hands-on skills courses.” He notes that the program strives to give students a broad background, and “we really try to emphasize building documentation – historic research, drawings and photographs – so you know what’s there before you begin work.”

Developing partnerships with other organizations is a big – and vital – part of the program. “They give us projects students can work on, and a lot of the adjunct instructors lead workshops in plaster repair, wood restoration, or blacksmithing.” Swerdloff says they work regularly with the Oregon SHPO and non-profits and government organizations, such as the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. “At the 1899 Knappton Cove Quarantine Station, now a museum, we rebuilt the porch, restored windows, and will do plaster workshops this spring,” he adds. Graduates may pursue further education in historic preservation, architecture, construction management or planning, or work in the preservation trades for preservation organizations.

Edgecombe Community College, Tarboro, NC

Located in the history-rich corner of rural Northeastern North Carolina, the Historic Preservation Technology program at Edgecombe Community College draws 8 to 12 part-time and full-time students each year from across the state to take part in the only program of its kind in the region. “We graduated our third class last spring,” says Monika Fleming, who has been the program’s chair since its inception in 2008.

The focus is teaching the hands-on skills necessary to repair and restore old buildings in the field: carpentry, masonry and roofing. Student lab/work situations can be at historic buildings, such as a local historic Rosenwald African-American School, as well as Norfleet House, an early 19th-century farmhouse relocated to the campus for restoration that now serves as a classroom and laboratory for the program. “The masonry class this semester is finishing the piers,” says Fleming. “Other classes are learning about painting, timber framing and carpentry.”

Edgecombe strives to meet the diverse needs of its historic building audience with educational opportunities at all levels. “We have added two more certificates to our program,” says Fleming, “so that now we offer a two-year Associates degree, a one-year diploma, and three different certificates for folks who just want to learn some skill, but not the entire program.” The school also continues to run weekend classes, and will host a preservation trades show in late April 2015 and participate in the National Trust Conference on Rosenwald Schools later in June.

Bucks County Community College, Newtown, PA

Another long-running course of study that has developed a singular approach is the Historic Preservation program at Bucks County Community College. “Next year we’ll be celebrating 25 years,” says coordinator Patricia Fisher-Olsen, “and over the last seven years, everything has really shifted over to the online arena, which we started offering in 2007.” She says online is increasingly where people want to take their education. “There’s so much more that can be brought to an online classroom these days, and we have a really good technical campus that’s helped us a lot.” Courses are offered both on-campus and online, including workshops, fieldwork and internships.

As uncommon as the approach is, so is the student base. “On a regular basis, we probably have about 35 students in the program,” says Fisher-Olsen, “but we’ve got students from coast to coast and have had as many as 80; it ebbs and flows.” As she explains it, the program’s reach is to people who want preservation education but, so to speak, don’t want to pay for a Master’s degree – or who already have a Master’s degree. “They could be architects or planners or folks working for an engineering firm or their town that want to augment their credentials, so they come to us.” As an example, she says they’ve had many people from the National Park Service enter the program. “We also get a lot of carpenters and masons that need preservation education to move up to their next level. These folks bring a wealth of information and another perspective to the classroom.”

Graduates of the program earn a 24-credit certificate, “college-level work for college credit,” stresses Fisher-Olsen, “not continuing education credit.” The school hopes to offer an AAS in Historic Preservation in the near future. In the meantime, students can earn an Associates in History with a concentration in Historic Preservation by taking an extra semester of courses to get the full certificate with the Associates.

Lamar Community College, Lamar, CO

In another creative approach to trades education, Lamar Community College has partnered with HistoriCorps® to reinvent their Historic Building Technology program as a field-based preservation school. “The partnership started winter of 2013, with the first year mostly spent building the curriculum around the core field school,” says Natalie Henshaw, educational programs manager at HistoriCorps, “and now the focus is on enrollment,” which stands at five students and growing across the program.

HistoriCorps is a non-profit entity created to fill the needs of the Forest Service and other land management agencies to restore their vernacular buildings in remote sites. “Our mission is very simple,” explains executive director, Townsend Anderson. “It’s historic building rehabilitation on public lands that engages volunteers, veterans, students, Conservation Corps members and youth.” They stress maintenance and repair, he says, which is at the core of historic preservation.

The Lamar program then is based upon the same idea, where students go out on HistoriCorps projects and learn in the field. “The advantage is they’re not learning about timber framing in a classroom,” says Henshaw, “they’re actually out doing timber framing, or out restoring a roof, and learning how building rehabilitation works on-site, including the business skills, such as completing a project on time and within budget.” Since HistoriCorps projects are in remote sites, classes pack in all the tools and experts, do the work, then pack out.

Each semester is made up of two online classes and a field school, which usually runs three to four weeks, says Henshaw. “So a student can go to a field school, and then they can be online.” Accreditation is in the form of what the school calls ‘stackable certificates.’ As she explains, “If you complete semester one, you earn a certificate; if you complete semester two, you earn a second certificate; if you complete semester three and your general education requirements, then you earn an Associates degree.”

As if this were not creative enough, Henshaw adds that the program is non-location-specific. “HistoriCorps projects can happen around the country, so a student in West Virginia could go to a HistoriCorps field school in West Virginia or Wyoming, and then take the online classes from their home. They don’t necessarily need to be in Southeastern Colorado.”

Timber Framers Guild, Amherst, NH

In America, formal building trades apprenticeships have a history of being few and far between, especially since the 1940s, but we’re happy to report that the program launched by the Timber Framers Guild (TFG) in 2010 is going strong. Created in response to the industry’s need for trained personnel, as well as to set standards for the craft and what skills and abilities a timber framer should have, the apprenticeship is a three-year combination of study and on-the-job training.

“The goal of any trade education is not to limit the learner in any way,” explains Curtis Milton, chairman of the program. “A lifelong learner with motivation can be what he or she chooses. What better path to a career as a designer or architect than training and experience as a builder?”

Apprentices work full-time under a registered journeyworker, while also completing specialized training through providers such as technical schools, online courses and Guild events. Though the program concentrates on timber framing, parts of the training reach across other trades, such as safety and first-aid and forklift operation – especially in regard to moving long and large timbers.

“So far our four graduates are still involved in the industry,” says Milton, who adds that while exact numbers are difficult to pin down, as many as 10 individuals have found work just through the contact form on the TFG website Apprenticeship page. The program complies with the Department of Labor regulations for an apprenticeship. To be considered for enrollment, prospective apprentices need to be employed under a registered journeyworker, meet the program requirements, and make a financial commitment to the program that allows it to fund the training of the apprentice and the journeyworker.

More Trades Education

Algonquin College

Carpentry and Joinery Heritage Program

1385 Woodroffe Ave.

Ottawa, Ontario, K2G1V8

Canada

Historic Preservation Training Center

National Park Service

Historic Windsor Inc.

& the Preservation Education Institute

National Center for Preservation

Technology and Training

645 University Parkway

Natchitoches, LA 71457

Preservation Trades Network (PTN)

Snow College

Traditional Skills Workshops

150 College Ave.

E. Ephraim. UT 84627

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.