Features

The Architectural Legacy of Richard Morris Hunt: Drawing Inspiration from the Beaux-Arts

The architect’s pencil, pen, and brush are the instruments of eternal utility and beauty, rendering a building a reality on paper in the form of the drawing. Greek columns, egg and dart motif, cyma reversa moldings, masks of Apollo and images of Athena, Gothic lancet arches, trefoils, and a pantheon of limitless details in architecture have been expressed first in line and sketch. Richard Morris Hunt (1827–1895) worked in this time-honored method; his drawings served as windows onto his evolving aesthetic and how he envisioned and refined architectural schemes. This approach reflected the disciplined training of architects at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the premier school of the fine arts in Paris during the 19th and early 20th centuries. As the first American to attend the Ecole, Hunt experienced a course of study focused on the rational development of a building’s plan and elevations. First, the architect produced the equisse, the quick sketch encapsulating the main concept, then worked for several months on the projet rendu, the rendered project with all details. Elaborate as the projet rendu could be, it had to retain its essential feature from the original equisse.

In addition to time studying in Paris, Hunt took sketching tours throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, resulting in his connoisseurship of historic ornament. The drawing became the vehicle for study and, in his professional life, for working out solutions in many scenarios for design issues. It is through Hunt’s use of line, pen, graphite, and watercolor that he brought his ideas to fruition and his buildings to full form. These provided a vision for his clients, and he often created many versions of a facade or the profile of a column or arch to engage and, often, enchant his patrons as he guided them to an architectural decision.

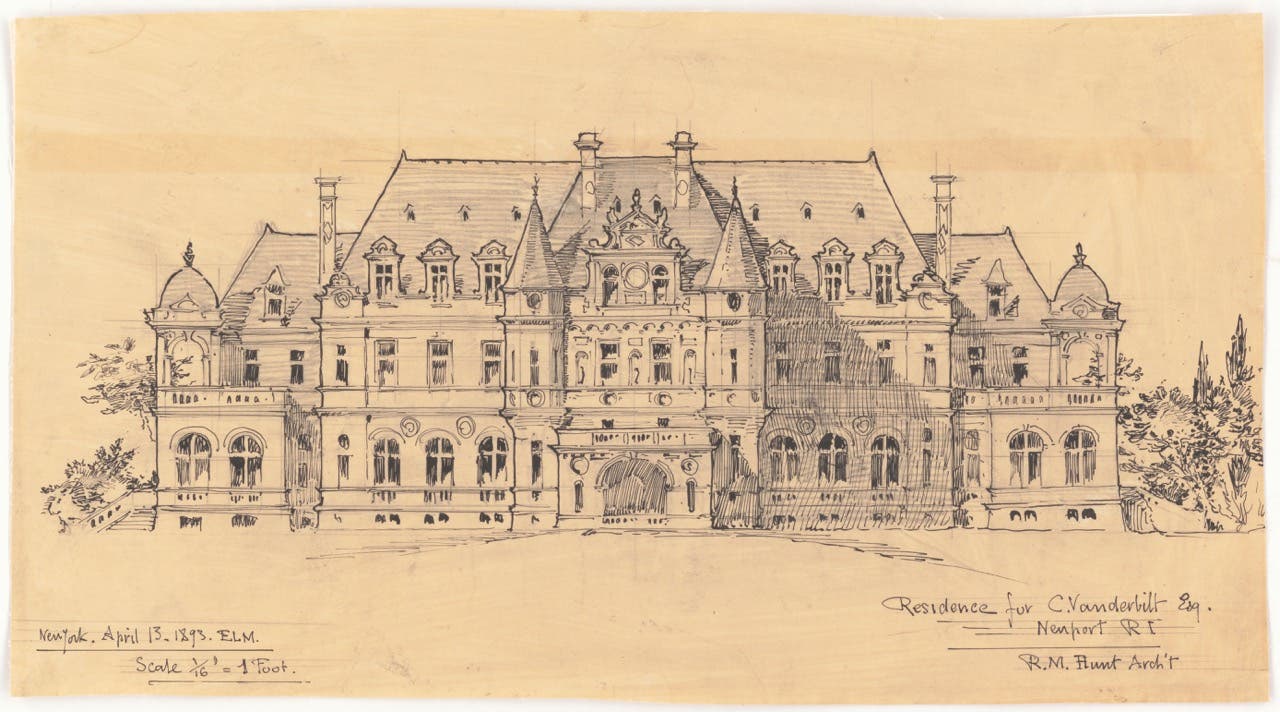

In projects for the Vanderbilt family, Hunt rendered exquisite images for their Newport, Rhode Island, summer houses, Marble House (1892) and The Breakers (1895). Both buildings served the architect’s dream of classical houses on cliffs overlooking the sea. Hunt’s drawings enabled the Vanderbilts to see a grand architectural scheme that would imprint their names on a fashionable resort, one where the world was watching as members of one of the richest families in the United States were affirming an identity as empire builders.

William and Alva Vanderbilt’s Marble House is a temple to gods and kings set down by the sea. Inspired by the Parthenon, the temple to Athena, and the Petite Trianon, built for Madame de Pomadour, Alva invoked two jewels of classical architecture that also happened to be connected to powerful women. Hunt’s renderings of the main facade of Marble House are truly one of his most sublime. He had experimented with urns along the rooftop balustrade and additional ornament, but eventually scaled back on these features and allowed the rows of pilasters and the entrance colonnade to take center stage. The interiors defined Gilded Age opulence, such as the ornately carved Gold Salon and the Dining Room sheathed in rose-colored marble. For all its rich materials, the drawings of the Dining Room, devoid of color, speak to Hunt’s organization of the interior into a series of arches and pilasters, lending classical discipline to the space. He also draws in the grain of the marble to indicate how the stone patterning would affect the design.

The drawing for the main hall takes a similar approach with lush yellow Siena marble with little decorative carving to detract from the color of the stone. Hunt does use a Vitruvian scroll as a border for the base of the stairs and leaves circular discs open on the upper level of the stair landing. These would be filled by white marble profiles of Richard Morris Hunt and Jules Hardouin Mansart, the architect of Louis XIV’s Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. At the center of the wall scheme is a place for a copy of Bernini’s bust of the king himself, Louis XIV, given a place of honor at the center of Marble House. Lavish material carefully structured by classical framing, columns, and arches in what could be described as disciplined opulence, if this term can be believed, defines the character of Hunt’s designs for Marble House.

The Breakers is an Italian Renaissance style palazzo in Indiana limestone. There is a stately quality to the house appropriate to the power and position of this senior branch of the family with Cornelius at its head as Chairman and President of the New York Central Railroad and Alice as its matriarch. Hunt provided several versions of the house in the French and Italian Renaissance modes. After several iterations, he brought in the sprawling wings of his initial designs, adding a third story onto the house, making it higher, and replacing the side wings with parterre gardens. The interiors are arranged around a central great hall, in the manner of the open-air courtyards of Italian palaces. For ornamental details, Hunt referenced his copy of the Palazzi di Genova (1622) by Peter Paul Rubens. Triumphal arch motifs for windows, vaulted loggias, and elaborately carved column capitals derived from Genoese palaces appear throughout the facades and interiors of The Breakers. These features give a sense of appropriate scale to the monumental stone form of the house, organizing each floor into discrete units. The ornamentation gives the great house a festive air. Cherubs, goddesses, garlands of flowers and scallop shells, and acorns and oak leaves swirl and sprawl over limestone halls and gilded wood reception rooms.

Marble House and The Breakers illustrate how a classically trained architect conceived of designs, both the grand forms of great houses and the details of the most delicate ornament, and worked his way through to their final manifestation in stone, wood, stucco, plaster, metal, and gilding. In Hunt’s case, his drawings leave us with a record of thought processes and aesthetic decisions that determined the making of landmarks. TB