Features

Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village

Thomas Jefferson had a vision for the nation and its architecture, most fully expressed in his design for the University of Virginia. Emerging from the Georgian tradition in colonial Virginia building, Jefferson initially embraced the Palladian inspirations for American architecture in classical proportions and porticos. Then, he went to Paris as U. S. Minister in the 1780s and nothing was ever the same.

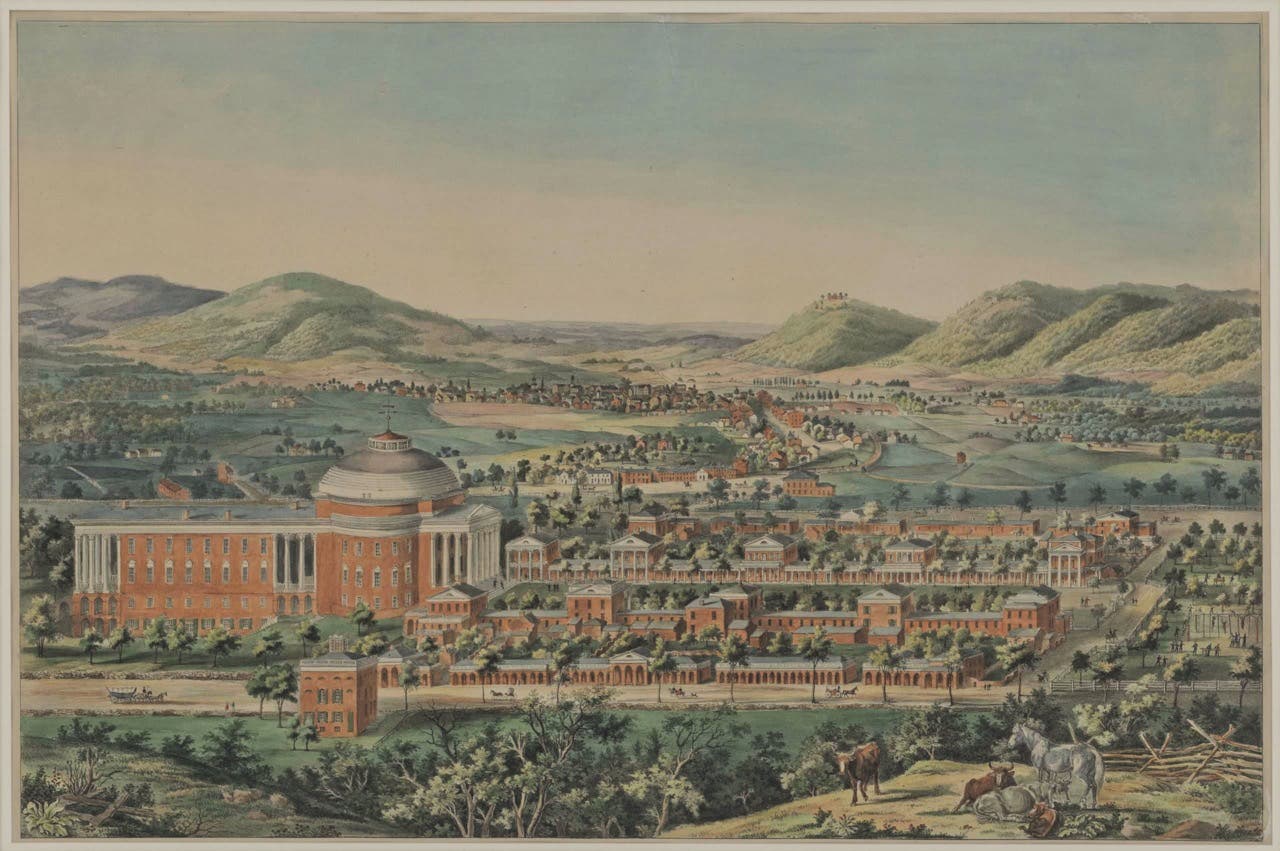

Working in the manner of the gentleman amateur architect of the 18th century, informed by pattern books to inform and guide, Jefferson’s approach evolved through practice at his plantation, Monticello, in Charlottesville, and in the university he would create within view of his mountaintop home. His plan for the university, conceived of and known to this day as the “academical village,” and its central greenspace, called “The Lawn,” is a study in the architectural expression of the ideals of utility and beauty, of theory and practical adaptation to site and materials. It is a vision that Jefferson made real.

With the establishment of the university in 1819, Jefferson set to preparing drawings and planning work from 1821 until his death in 1826. He firmly believed that an educated populace formed the only stable base for a fully functioning democracy. The university would serve this vital function, a place of sound learning and ideal symbols, writing in 1820, “this institution will be based on the illimitable freedom of the human mind, for here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.”

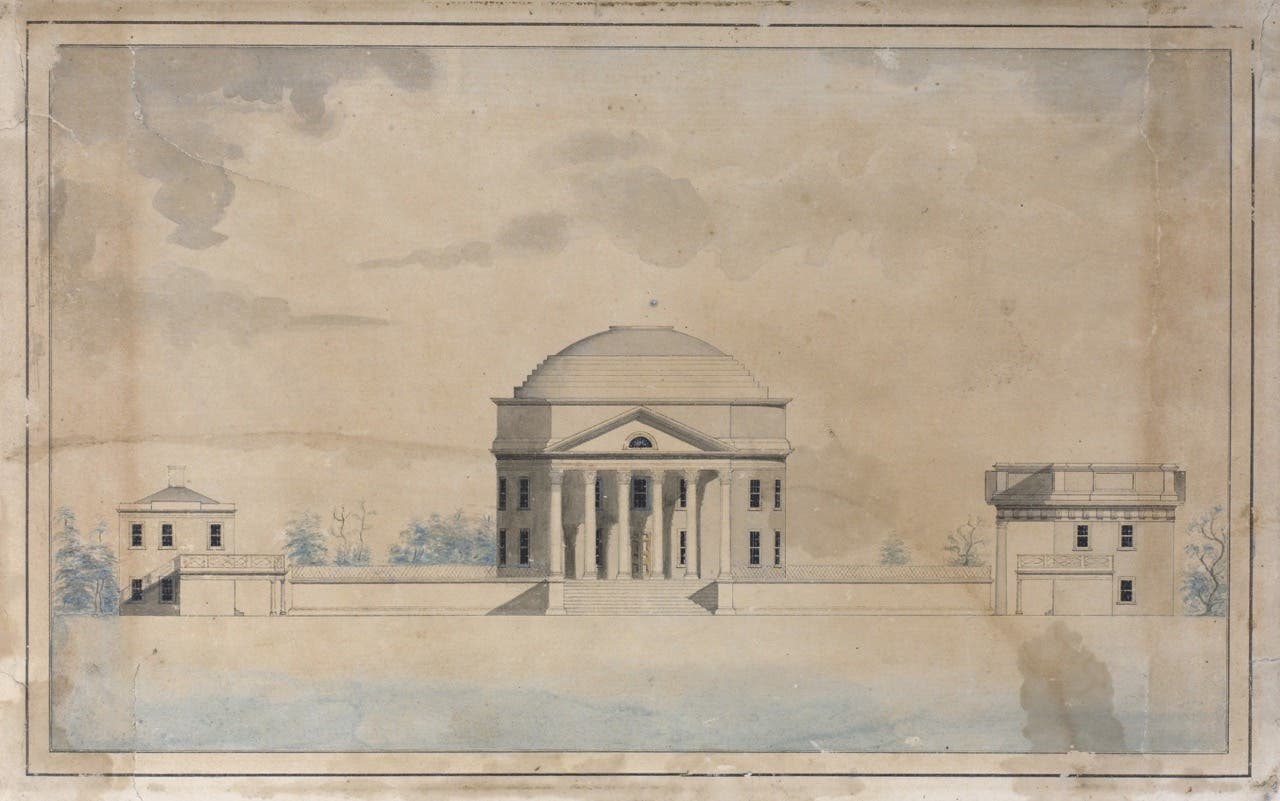

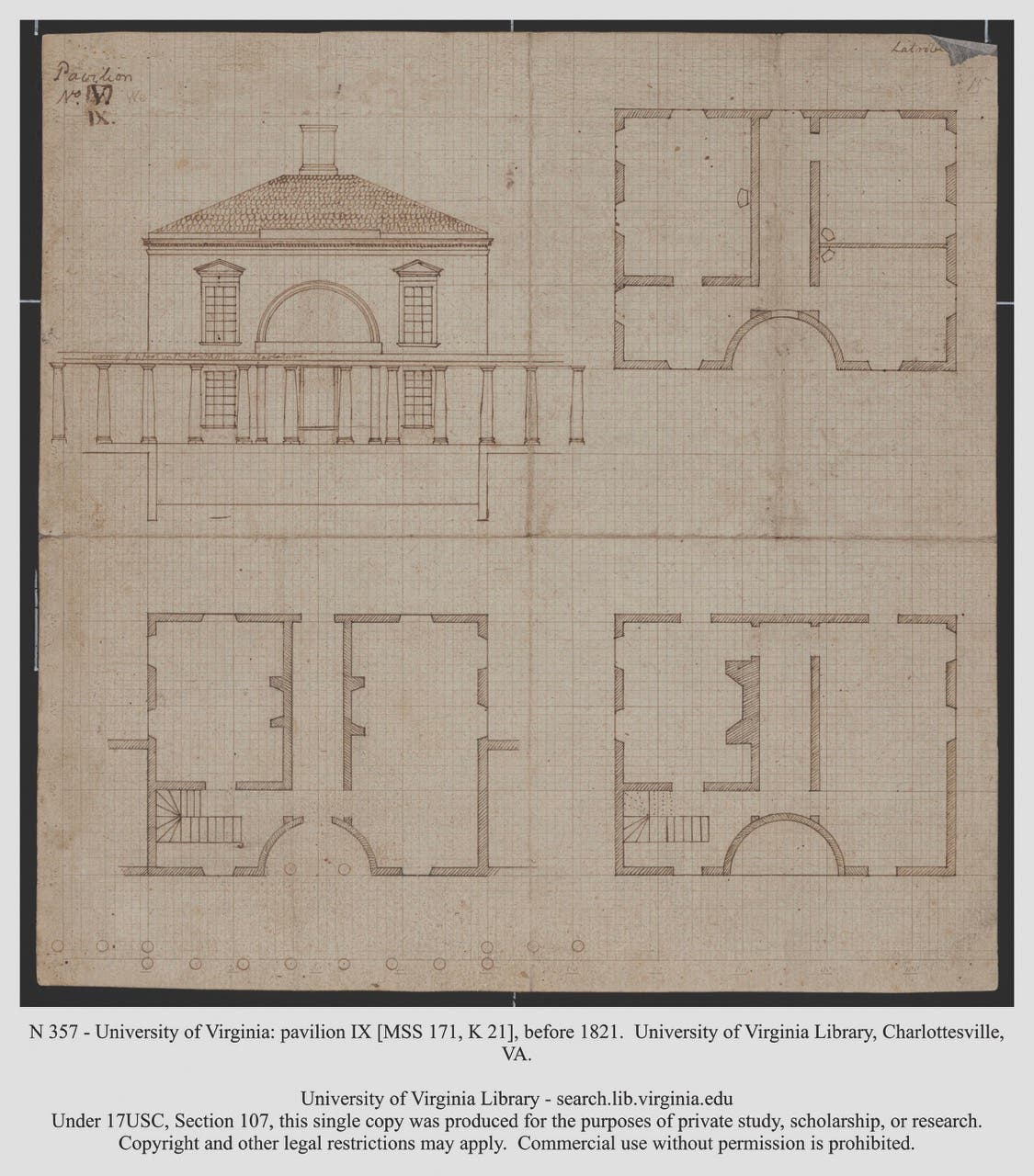

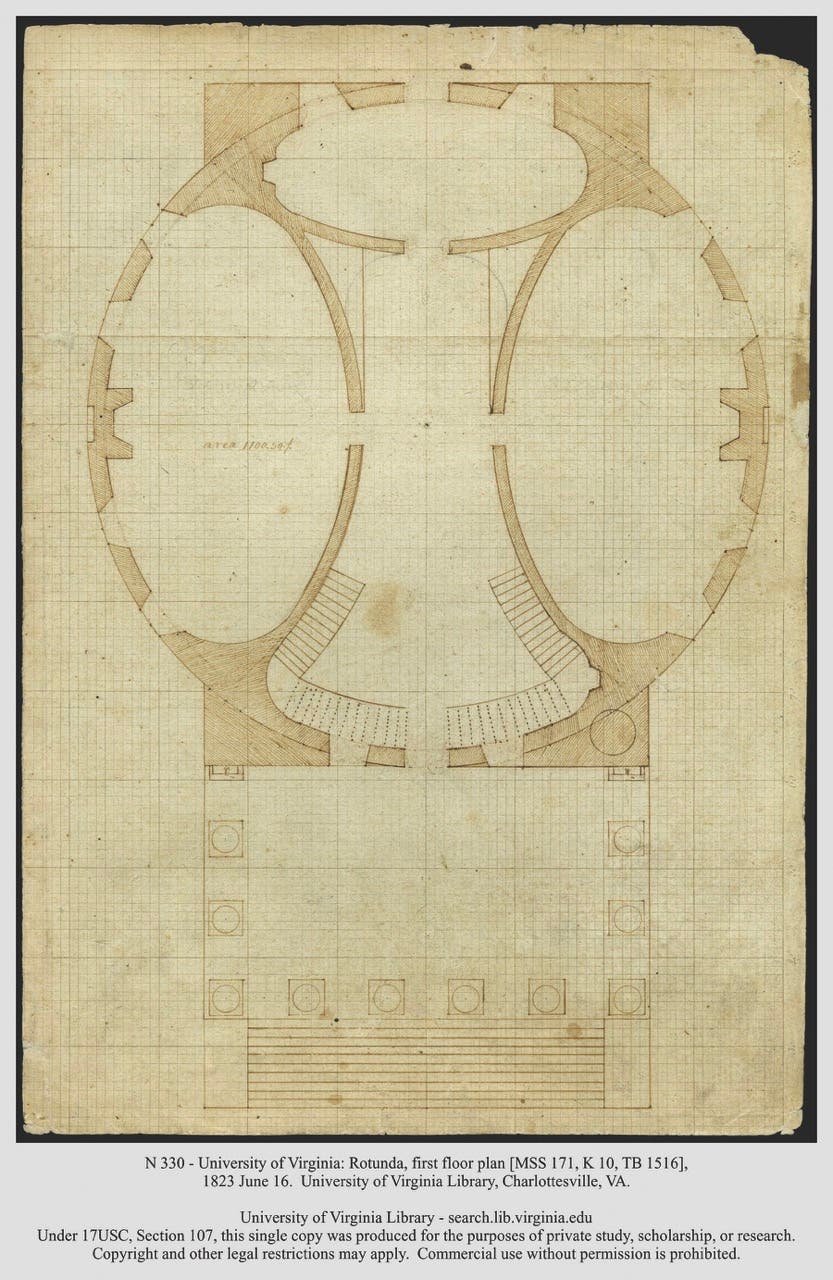

At the visual and physical center of the plan is the ultimate symbol of Classicism: the Rotunda, a half-scale version of the Pantheon in Rome, a perfect sphere at the heart of the academical village, with two ranges at either side consisting of one-story student housing connecting to pavilions with classrooms and accommodations for teachers. Each pavilion, five on the east side and five on the west side of the Rotunda, represented an academic discipline, as conceived by Jefferson, to be occupied by a professor of the “useful science” with which it was associated.

Student rooms, teachers’ housing, and classrooms form an ensemble connected by colonnades, which offers shelter from the weather and partially screens the utilitarian areas behind the dormitories from public view. Walkways on the roofs of the colonnades are lined with Chinese Chippendale-style railings.

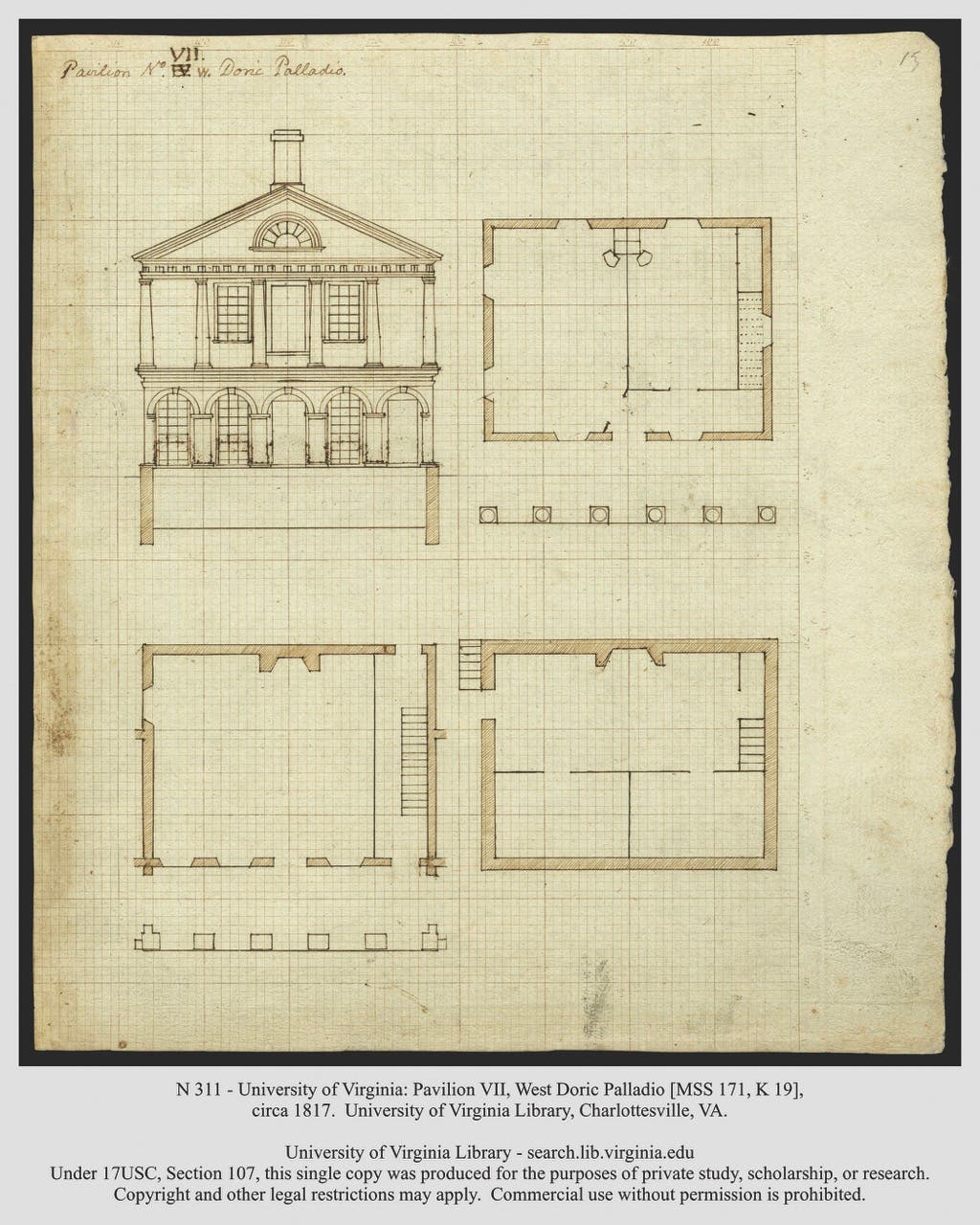

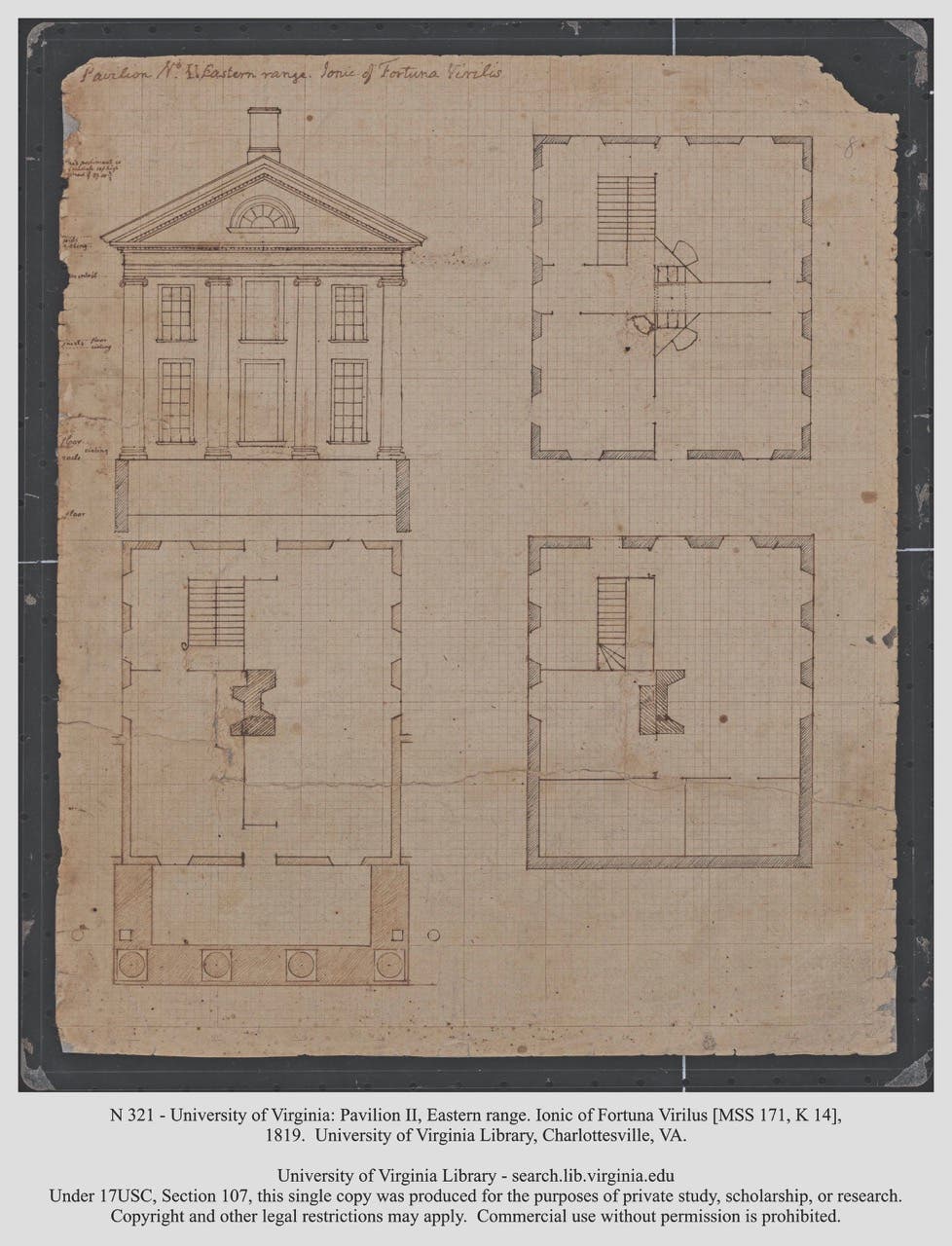

The pavilions are studies in historic and contemporary (to the 18th century) classical architecture and served as, in Jefferson’s view, good examples of the classical orders and of the resolution of design issues from walkways to changes in grade and the disposition of service areas.

Constructed in the red brick typical of Virginia buildings for centuries, the forms and ornament used by Jefferson came, in great part, from his time in Paris as U.S. Minister Plenipotentiary (1784-89). Witnessing the creation of neoclassical masterworks, such as the Hotel du Salm, and visiting historic sites informed Jefferson’s already extensive knowledge of architecture. His plan for the university recalls Louis XIV’s retreat, Marly, with its central pavilion and ranges of freestanding pavilions at either side. While Louis, the Sun King and center of his universe, dominates the center as a landmark to absolutism, Jefferson’s Rotunda at the university served as a library, a monument to enlightenment. Jefferson also knew of the Hotel Dieu, a hospital in Paris with a series of pavilions and colonnades. These French models and his expertise in Palladian sources would be interwoven in his scheme for the university.

Jefferson referenced the classical orders as rendered in Andrea Palladio’s Il Quattro Libri (The Four Books of Architecture) and Fréart de Chambray’s Parallèle de l’architecture antique avec la moderne (1650) in schemes drawing upon sources from ancient Rome to the Renaissance. Jefferson devised all five of the Pavilions on the east Lawn, including Pavilion VIII, in 15 days in June 1819. He also sought the advice of architects William Thornton and Benjamin Henry Latrobe to further refine the general ideas for his grand vision of the academical village as a model for learning about the history of classical architecture. For example, Pavilion VII is in the Doric Order, Pavilion II the Ionic Order based on the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, and Pavilion III the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina as featured by Palladio. Encountering these buildings on one’s daily rounds as a student served as a walk through history and a lesson in design.

Treatment of the university’s site reveals Jefferson’s adaptive skills. Set on a hill, the Rotunda is at the highest point while The Lawn slopes down in two places as one proceeds along the side ranges with pavilions. The end of The Lawn remained open to the vista of expansive countryside, a symbol of the nation’s continuing expansion—the old classical world, history enshrined in the Rotunda; a new world of the future built on classical ideals waiting to be settled in open view. Manifest Destiny, for good or ill, given architectural form.

While Jefferson dreamed of the future, he also dealt with the functional concerns of the present in daily life at an educational institution. A series of gardens and a second set of ranges for student housing are placed on the sides of the hill to the east and west of The Lawn. The change in grade of the topography allowed for service areas in raised basements behind each building with a work yard, spaces used and lived in by the enslaved Africans and African Americans who built and maintained the university. In this, the academical village reveals the nature of American history in full, in its contradicting images of soaring classical forms and its social inequalities. TB