Profiles

Classical Architecture Contributor: Thomas Gordon Smith

Whether you call it traditionalism, neo-historicism, or even simply revivalism, new classical architecture is a movement that seeks to re-ignite the flame of traditional architecture, and one of its leading lights is Thomas Gordon Smith (www.tgsarch.com). A man of many activities and, according to author and educator Steven W. Semes, “irrepressible attraction to beauty,” Smith is perhaps most widely known for putting the School of Architecture at the University of Notre Dame on the classical map.

With characteristic modesty, Smith is quick to correct any notion that he is the originator. “The program had been going on for a long time—back into the 19th century, in effect—and had plenty of students,” he explains. However, by the time he arrived in 1989, the perception had been that the course of study was fairly weak, leading Notre Dame to search for a new chair. “They were looking for a fresh sense of leadership, not a new direction, per se,” explains Thomas’ wife Marika Wilson Smith, “but they also desired change that would foster more professional and academic leadership coming out of the students at Notre Dame.”

Smith’s response was to redirect the program away from the modernist concentration that dominated at architecture schools towards teaching new classical architecture. “What we were able to do is change to a classical perspective,” explains Smith, “which means responding to and re-animating antiquity, as well as the Renaissance and, certainly, the period during the 1800s and later within the United States.”

Once the University decided to hire Smith, it grew more intrigued by his ideas. “We were fortunate to have terrific support at the top level of the University,” he says, referring to visionary and mentoring individuals, such as the provost and a very active alumnus. “Their help, the aid of some of the existing faculty, and the development of new faculty, really made the classical program a possibility.” What’s more, the program also took on a new position and prominence within the University itself. Marika points out, “One of Thomas’ first efforts was to restructure the School of Architecture as separate academic unit—independent of the College of Engineering, where it had been formerly.”

Smith adds that novel as it was for Notre Dame, the idea of a classically oriented program is not unique. “There are several similar places in England, and a few in the United States,” he says. “In fact, such classical programs have multiplied to become, oddly enough, what you might say are the avant-garde.”

Despite the promise, the conversion to classical did not meet with instant or unanimous approval. “It’s a five-year program, and students at the upper level just weren’t interested at all,” says Smith, so they kept the program as is for those with only two or three more years to finish. “It was with new people—some of whom were shocked, but others who were responsive—where we began to build up the classical program.”

Now in its third decade, the program has clearly been bearing fruit. “When young people do finish their architectural studies, there are opportunities to get into architectural practices throughout the United States that are completely involved with the renovation of classical elements—though how they are interpreted varies.” Perhaps most important though is the impact on people who want to build a house, or any kind of structure. “They’re learning that, ‘There’s something out there that we like, and now we can have it done.’”

From Old World to Golden State

Where did an aspiring architect get bitten by the classical bug if they’re too late to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts of the 1890s, but too early for the first new classical grad programs at Cornell and MIT in the 1970s? “It’s never very clear,” says Smith, speaking for many, “but in my case, I spent a year traveling with my family in Europe, especially France and Italy, when I was 18 or so. That was tremendously valuable.”

What impressions registered on the right brain of a young mind came into clearer focus when he moved to college. “Certainly I was very fortunate being from Berkeley, California, with all its universities and different aspects of tradition,” he says. In fact, the larger bay area was itself a rich environment, he says, because in the early 20th century there were some great architects building traditional buildings there, “the typical thing to do at the time, of course, but of very high quality.”

He recalls being at first disappointed that he didn’t get into some East Coast architecture school. “Afterwards I realized I didn’t need those places because they’re so tight that, while I might have survived, they wouldn’t have had the positive nature of the excellent teachers at Berkeley.” Marika, then also studying at Berkeley, agrees. “His professors weren’t necessarily enthused about some of the ideas he was developing, but it was a much more open school; they didn’t see classicism as something archaic.” Or as Smith puts it, “Even if not interested, some were at least able to avoid the idea that ‘It’s over and you can’t do this anymore.’”

Moreover, Smith had the good fortune to work extensively with architectural historians such as David Gebhard, one of the lions of California historic preservation, who was teaching at Berkeley. “Gebhard enjoyed having Thomas as a design student, because he didn’t normally teach design,” recalls Marika, “yet he was intrigued to have a student who wanted to build new buildings that had some interest and richness.”

Smith concurs. “A number of us wanted to do something new—to be able to really open things up again and not just be so closed down.” Smith also took a course from the postmodern architect Charles

Moore, who was a guest lecturer at the school, and found an affinity with some of his ideas.

However, during the heyday of modernism, and the aftermath of the turbulent 1960s, not everyone condoned or understood such activity. Remembers Smith, “One professor asked, ‘What is it you want to do—applied archeology?’”

Marika shares an equally telling tale of the graduate program of PhD students. “A friend brought one of his professors to see some of Thomas’ drawings for little, hypothetical houses, one of which Thomas had labeled Doric House.” As the story goes, the professor was neither impressed nor pleased. “’Who gave you permission to design a Doric House?’ she inquired, as if it was something terrible.” Adds Smith with a chuckle, “As far as the professor was concerned, these ideas were opening a Pandora’s box. Better that they should stay safely in the textbooks and not influence anyone.”

After setting up his own architectural practice in San Francisco, Smith began to attract attention in the 1970s and ‘80s with a series of projects on a broader canvas. Beginning with the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome in 1979, he caught a bit of international limelight with his façade and exhibition at the “Presence of the Past” Venice Biennale of 1980. “It was the height of postmodernism,” recalls Semes, now associate professor at the Notre Dame School of Architecture, “and for me Thomas’ evocation of the Roman Baroque in his façade (one of over a dozen constituting the Strada Novisssima or ‘new street’) was like a lightning bolt in the way it suggested that the architectural past could be incorporated into the present.”

In 1988 Smith published Classical Architecture: Rule and Invention just before coming to Notre Dame to take the helm at the School of Architecture.

Classical Principles into Practice

After chairing the architecture program from 1989 to 1998, Smith continued to teach while putting more emphasis on his own, existing architectural practice. “Even while chair, I was able to do some projects, both theoretical and built. Then afterward I continued to teach full time, but also have more opportunity to build at a larger scale, including two very large projects for Catholic organizations in the Midwest.”

Indeed, ecclesiastical projects have become something of a specialty for Smith. “I’ve had projects for houses or educational buildings, but even in learning how to become an architect, I was always interested in ecclesiastical projects—hypothetical ones, for example.” Says Semes, “It is appropriate to mention that Thomas’ religious life has been central to his career. It is no accident that he has flourished in the Catholic milieu of the University of Notre Dame, or that a rebirth of classical architecture occurred there under his leadership. For Thomas, the classical tradition is the natural language of the Church.”

While Smith’s project list is certainly strong on the classical and ecclesiastical, he is also more than comfortable with secular structures. “Thomas has really enjoyed working on various museum structures,” explains Marika. “He’s done additions to two museums in Indiana, and worked on the renovation of the Classical Galleries in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, completed in 2007.” This multi-room suite devoted to American furniture and decorative arts created between 1810 and 1840—the Greek Revival era—is a good example of the intersection of classical and secular in Smith’s work and his unforced courtesy. “I was very fortunate to work closely with people who were making decisions about the building—ideas about design as well as how to use these areas.”

In addition, he designed the family’s first home, Richmond Hill, in Richmond, CA. “Thomas and I built it for our family on a small 25 x 80 ft. lot,” says Marika. “With the required set-backs, the house could be a maximum of 19 ft. wide. For better views, the living areas were placed on the second and third floors; the ground floor has bedrooms, bathrooms, and a laundry.”

“Thomas painted the frescoes in the finish plaster in the living room,” she continues, “These have a complex iconographic program based on cycles of time, expressed in the Greek myth of Demeter & Persephone in a series around the upper level; the ages of man and woman from conception to death in the ceiling; depictions of the seasons in frescoed floral arrangements; and vignettes of nine gasoline stations, one from each decade of the twentieth century, which is one of the references to the distant view from the living room to the northwest of Richmond’s massive oil refineries.”

Church projects though come up often in a Smith conversation and with a surprising spread of scale, style and time. “When Thomas designed a new parish church in Dalton, Georgia, near Atlanta,” explains Marika, “as is common, building was completely new to the building committee.” Not so however for a group of Benedictine monks who wanted a new monastery in Oklahoma. “They were amazing, with very clear ideas of what they like, don’t like, and exactly what they had in mind for their layout and other practical ideas.”

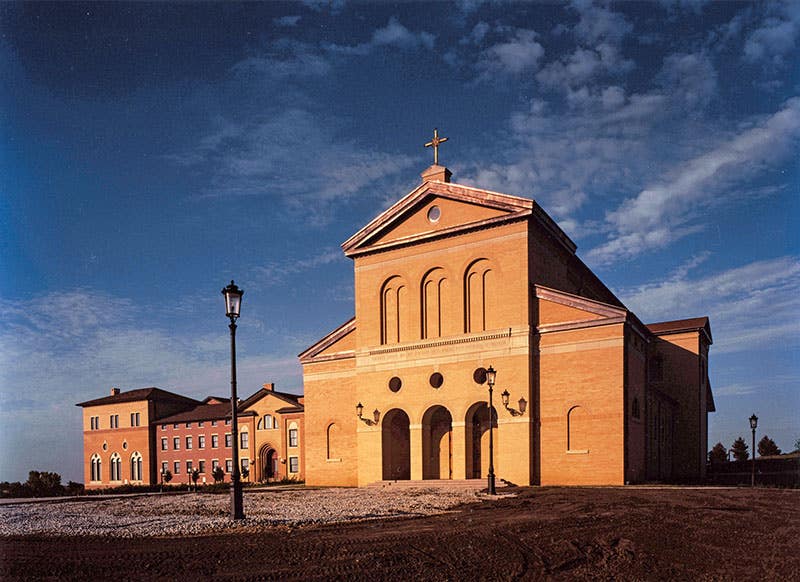

It should come as no surprise because the monks not only had built five other monasteries in recent decades, they had a successful model. “Their mother church in France is in a very simple, severe, kind of Romanesque style, with very little ornament, so that was their request to Thomas.” But not their only request. As Smith explains, “The Abbot also said, “Well, can you also make it so it will last 1,000 years?’ Since their monastery in France dates to 1100, they’re not joking when they say they want something that’s very strong, very beautiful, and very practical.”

Given the monks’ meticulously thought-out program, and their long view of history, the monastery’s construction will be measured not in months, but years, with about half still to go. Adds Smith, “Building in the United States is, of course, different than building in Europe—being able to respond to the antiquity of these styles and aspects of the materials.”

Even so, he says the notion that traditional architecture can be viewed as a cookie-cutter recreation is never really the situation. “Whether it’s the place or the materials or resources that are available, every time it’s always a different environment—which is very positive.”

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.