Features

Reviving Historic Theaters: The Shows Go On

By Martha McDonald

Historic theaters represent a particular time in the timeline of entertainment. In their prime, they were numerous, the designs were often classical and elegant, and they were an important part of their communities. While some were grand and glorious, others were more modest; yet all were significant parts of the neighborhoods. As times changed, along with tastes in entertainment, many were abandoned and fell into disrepair.

Now, some of these theaters are making a comeback and are being adapted to today’s technology and entertainment tastes, thanks to skilled architects and craftspeople, developers, historic tax credits and enthusiastic communities. As the theaters come back, often so do the communities they serve. This article will survey theater restoration projects by two firms, Martinez+Johnson of Washington, DC, and New York, and Mills + Schnoering of Princeton, NJ, as well as provide photos and information on other theaters around the country.

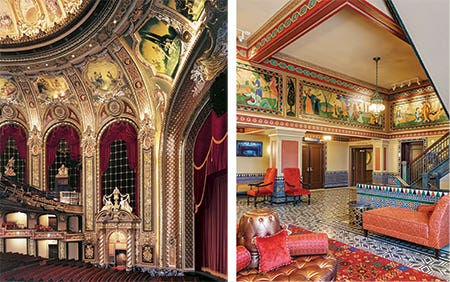

In the New York/New Jersey area, five grand, ornate theaters built in the late 20s by Loew’s were known as “Wonder Theaters.” These included the Kings Theatre in Brooklyn and the Loew’s in Jersey City, both designed by Rapp & Rapp in the French Renaissance style; The Valencia in Jamaica, Queens, NY, designed by John Eberson in the style of a Spanish villa; the Paradise Theater in the Bronx, NY, designed by Eberson in the style of the Venetian doge’s palace, now run by the World Changers Church, and the United Palace Theater on 175th St., in Manhattan, designed by Thomas Lamb.

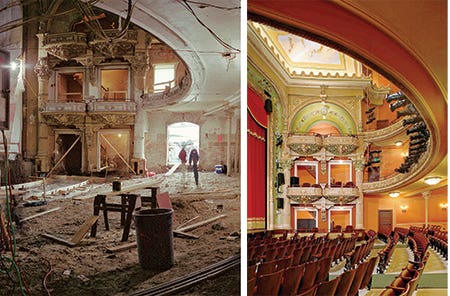

One of these, the Kings Theatre on Flatbush Ave. in Brooklyn, NY, has recently been restored and updated. The effort was led by Martinez+Johnson Architecture of Washington, DC, and New York. The $95-million project took a number of years and involved major structural work as well as the restoration of the elegant historic interior. Martinez+Johnson started working with historic theaters in the late 1980s. “We worked on the Warner Theater in Washington, DC, but the first project that we did as M+J was the Boston Opera House, a Thomas Lamb theater,” says partner Gary Martinez, FAIA. He explains that he met people from ACE Theatrical Group while working on the Warner, and that has led to many other collaborative projects.

The Boston Opera House, with just under 2,800 seats, was a stage replacement project, says Martinez. “Like many of the venues that we work on, it is designed for multi-use programs. It was designed for touring theatrical shows and is also the home of the Boston Ballet.”

Another early project was in El Paso, TX, where the firm renovated an old movie house so that it could accommodate the symphony as well as touring companies. “The stage was too small. It needed significant backstage support spaces.”

“We learned our craft on these early venues,” says Martinez, adding that 90% of the firm’s business now is theater work.

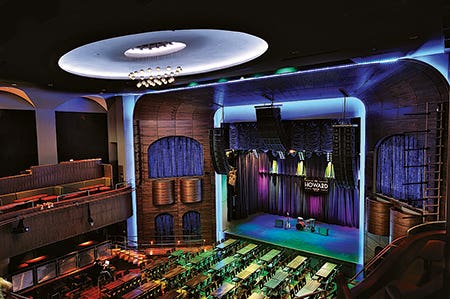

One of M+J’s most significant projects was the Howard Theater in Washington, DC. “This is the oldest African American Theater in the U.S.,” he says. “It predates the Apollo. It was built by black entrepreneurs for a black audience. All of the major black musicians, actors and actresses, including Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, James Brown and Aretha Franklin, performed there at one time. It had been vacant for decades when we started work on it. It was a solid building, but the interior was totally gone. The only thing that was left was the shape of the proscenium and the shape of the balcony.”

He explained that at one time the neoclassical interior had been changed to a deco style. “That happened to a lot of theaters in the 40s,” Martinez notes. “We took it back to its neoclassical look. The interior had to be completely replaced.”

The Howard, with seating for 600 and standing room for 800, was completed in 2012 for $25 million. Martinez notes that the renovation of an historic theater can “easily be in the $50-million range, and that a fast project takes five years. Most take 8-10 years. A large house is 2,200 to 2,800 seats, but we have done smaller houses too.”

Martinez explains that while some are private projects, such as the Boston Opera House that was financed by Clear Channel Entertainment, most of the projects that M+J work on are a public and private collaboration. In fact, his meeting of members of ACE Theatrical Group, particularly David Anderson, who is now president, has resulted in a very successful collaboration over the years.

“We work with the ACE Group,” he says. “They love the historic theaters and they know how to operate them. They look for venues with the capacity to bring in larger shows, and they also set them up for local shows. David’s team knows how to put together the funding – and that can take time – and how to run the projects. They take a long-term lease, get it designed and built and then take over the operation of the theater. The goal is for it to become sustaining.”

He adds, “The ACE Theatrical Group has a 40-year background in entertainment and the performing arts. They know the producers of shows, work with companies with robust programs and have deep ties in music, all kinds of music.”

The Kings Theatre in Brooklyn is set up that way, Martinez notes. The project had a grant ($50 million) from the city, organized by the former mayor, Marty Markowitz, as well as investments by ACE. Federal and state historic tax credits also played a role. “These funds had to be raised through different programs and it takes a long time to make that happen. ACE is brilliant at this,” says Martinez.

He explains that the Kings Theatre originally had 3,600 seats, with about one-third of them in the shallow, small balcony that wraps around three sides of the theater. “I see it as a transitional venue. Vaudeville was still around, but these were movie houses. It was a powerhouse venue in Brooklyn for decades.”

The theater has a small presence on Flatbush Ave., and “then there’s a processional series of rooms as you enter. It was important to everyone that the theater be brought back to its original significance. Even the early requests from the city emphasized a high level of restoration of the public spaces.”

Major structural improvements were also made. For one thing, three quarters of the orchestra and two-thirds of the balcony were re-raked for better sightlines. “It had been raked for movies,” Martinez says. “For live entertainment, you have to have a steeper rake. You were not looking up at a screen. So we had to change the flooring, but it blends in. I challenge anyone to come in and notice that the floor had been changed.” Read more >>

In addition, M+J also added concessions, lounges and 80 to 90 restroom facilities. “Very few historic building had enough restroom facilities,” he says. “The crowds came, saw the movies and left. Now we need lounges, concession areas and more restroom facilities. We often add 20 to 30 points of sale, 8 to 10 locations for bars and food. These have to be built in and they have to harmonize with the historic interiors.”

Other major work involved the stage house. “We were originally planning to replace the stage house,” says Martinez, “but it didn’t make sense economically, so we made changes. At stage right, we expanded it to give more for rigging areas and more space offstage. At stage left, we added a new loading dock. The street behind the theater, East 22nd St., was closed and re-mapped to accommodate two loading dock. These are about 3 ½ feet higher than the stage, so we had to add a very large lift to get material to the stage.”

He adds: “We kept the back wall of the stage, but built a bustle, a large room, to give more flexibility. We deemed that the original stage, about 32 feet deep, was deep enough for theatrical programs and for music, so we left it and built the loft space behind it.”

“These historic theaters are very complex”

Martinez notes, “you are dealing with material that’s 80 to 100 years old, with restoration techniques that are not widely known, such as craftsmen to restore decorative paint, plaster and millwork.” He notes that they saved as much of the original material as possible. “There was a huge amount of plaster damage. We worked with EverGreene Architectural Arts. They did a fantastic job. They took molds as early as we could because the plaster was dissolving off the walls.”

In addition, almost all of the light fixtures had to be replaced. “Almost every fixture was gone. I think there were only seven or eight left. They all had to be reproduced, working from photos.” St. Louis Antique Lighting created these fixtures.

On the exterior, M+J revived the public entrance. The terra-cotta façade was restored by Building Conservation Associates. The marque was also returned to its original appearance.

In addition to its collaboration with the ACE Theatrical Group, Martinez+Johnson also regularly works with Shuler Shook Theater Planners.

“These buildings are a very important part of the community,” he stresses. “The reclamation of these venues speaks to the social and cultural fabric of the community. It is really a major act of repair. In many cases, it means that the community is re-dedicating itself to new growth.”

“The change usually starts about 8 to 10 weeks after the opening of a theater,” Martinez notes. “In the years that we were working at the Kings Theatre, we could see things picking up speed, restaurants moving in. A hotel is now being built across the street. It was an abandoned building before.”

He adds: “Theaters are really significant centers for the community. It can be very emotional. People were literally crying in the lobby when the Saenger re-opened in New Orleans (See Traditional Building, August 2014). It became symbolic of the city coming back from Katrina, a symbol of rebirth, as did the Howard. People’s lives are touched by these venues.”

Another firm that has developed a specialty in restoring theaters is Mills + Schnoering Architects of Princeton, NJ, (formerly Farewell Mills Gatsch Architects, LLC). A full-service firm that focuses on cultural, educational and government projects, it has seen a growing interest in theater restoration. “We do extensive in-house historic research with all projects, including theaters, whether or not it is a National Register project.” says Meredith Arms Bzdak, partner.

Partner Michael Schnoering, AIA, the firm’s theater specialist, notes that cities of all sizes and campuses are realizing the value of restoring their historic theaters. “People are seeing the economic value,” he says, adding that theater work is often more complicated than other types of restoration projects. “There are a lot of technical requirements that theaters bring. They can be very complicated. There can be extensive power, HVAC and public requirements.”

Schnoering notes that the theater’s specialty was launched in the 1990s.

“We worked on a couple of projects in the 1990s. The most significant was the State Theater in New Brunswick, NJ. Our first comprehensive theater design and construction project was for the NJ Shakespeare Festival, completed in 1998. It involved a full renovation and addition to a gymnasium at Drew University. From there, it took off.”

One of the firm’s recent projects is the renovation of the interior at the 1889 Wheeler Opera House in Aspen, CO. Known as “the crown jewel of Aspen,” the 500-seat venue is owned by the City of Aspen. The goal was to upgrade the capabilities, including the elimination of 35mm technology in favor of state-of-the-art digital cinema, add LED lighting and replace seating, and HVAC upgrades.

The biggest part of the project was the reconstruction of the balcony, keeping the historic character and improving sightlines. And, it had to be done in a tight timeframe. Planning on the $2.5-million project started in 2012, and it was completed in 2013 in time for the Wheeler’s holiday season opening night featuring Burt Bacharach. The actual reconstruction of the balcony was done in only three months, to minimize theater downtime.

In Bucks County, PA, Mills + Schnoering worked with private owners of the Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope, PA, Kevin and Sherri Daugherty, to restore and maintain the playhouse. Originally opened in 1939, the 439-seat theater was built on the remains of a 19th-century grist mill on the banks of the Delaware River. It had been closed for two years and had fallen into disrepair when the new owners acquired it in December of 2011.

This was another fast timeframe, since the owners hoped to open for the summer season. The goal was to save the landmark and create an active theater venue. Respecting the historic character, Mills + Schnoering made structural improvements on the interior and exterior, added new lighting and upgraded the HVAC system.

One of the more interesting parts of this project was the restoration by EverGreene Architectural Arts of a fire curtain designed by artist Charles Child, brother-in-law of Julia Child. It features a scene of New Hope.

The stage and performance facilities were also brought up to date. The new theater opened on time, on July 4, 2012, and now operates year ‘round. Future plans call for an enclosed deck with additional bars and restroom facilities and views of the Delaware River.

An early project that got the historic theater ball rolling for Mills + Schnoering was the State Theatre in New Brunswick, NJ. Designed by Thomas W. Lamb and built in 1921, it was intended for movies as well as vaudeville acts. It has gone through several renovations during its life, but it retains its historic character and is the center of the New Brunswick Cultural Complex which includes the State, the George Street Playhouse and the Crossroads Theater.

The team was brought in in 1992 to develop a master plan for the theater complex. This led to the creation of new loading docks for the State Theatre and the George Street Playhouse, and a new backstage addition for the State, adding room for wardrobe, upgrades to the dressing rooms and storage. In 2002 and 2003, the firm led a comprehensive restoration of the audience chamber, lobbies, and exterior terra cotta façade.

Mills + Schnoering is currently working on a new master plan for the theater complex which could provide a second 400-seat theater as well as better accessibility, expanded backstage facilities and additional offices and other facilities. “The property has a truncated corner,” says Schnoering. “A major part of the new plan is to straighten that out to expand the stage house. It is a comprehensive project. The State Theatre is fund-raising at this point.”

Another of the firm’s earliest projects (also completed as FMG Architects) was the $17-million restoration of the Westport Playhouse in Westport, CT. A tannery converted into a theater in an old barn, it had poor seating and sightlines. FMG started work in 1999 and worked there until the theater re-opened in 2004. FMG kept the auditorium and historic features as much as possible, reusing most of the barnwood timbers. “People were very attached to the theater and didn’t want to see changes,” says Schnoering.

A more recent project was the restoration of the Count Basie Theatre in Red Bank, NJ. With seating for 1,600, it was built in 1926. The initial phase involved restoration of plaster work and decorative painting (done by EverGreene), lighting, the auditorium and the lobby. The second phase was the exterior which included terra-cotta repair and windows. Recently, the firm completed an update to the master plan to expand the theater and is now working on a design for mechanical/electrical system upgrades and improvements to the theater’s fly tower.

This was another case where M+S worked with a nonprofit. “Master planning helps them see what the need and guides the fund-raising,” says Schnoering.

The firm also recently worked on the historic Civic Theatre in Allentown, PA, originally a 1,000-seat venue constructed in 1928. It is now a 540-seat venue that shows first-run films and also has a live theater program. Mills + Schnoering completed a master plan for two buildings, the Civic Theatre and Theater514 across the street. Schnoering points out that the exterior is in good condition, but “the interior needs work.”

Schnoering’s team completed a renovation to Theatre514 that included new risers, seats, accessible seating, railings, the relocation of the digital cinema projector and screen for better sightlines and lighting improvements, as well as new finishes for the interior walls and flooring. Mills + Schnoering has just completed a new master plan that addresses lighting, concessions, accessibility and backstage improvements. TB