Features

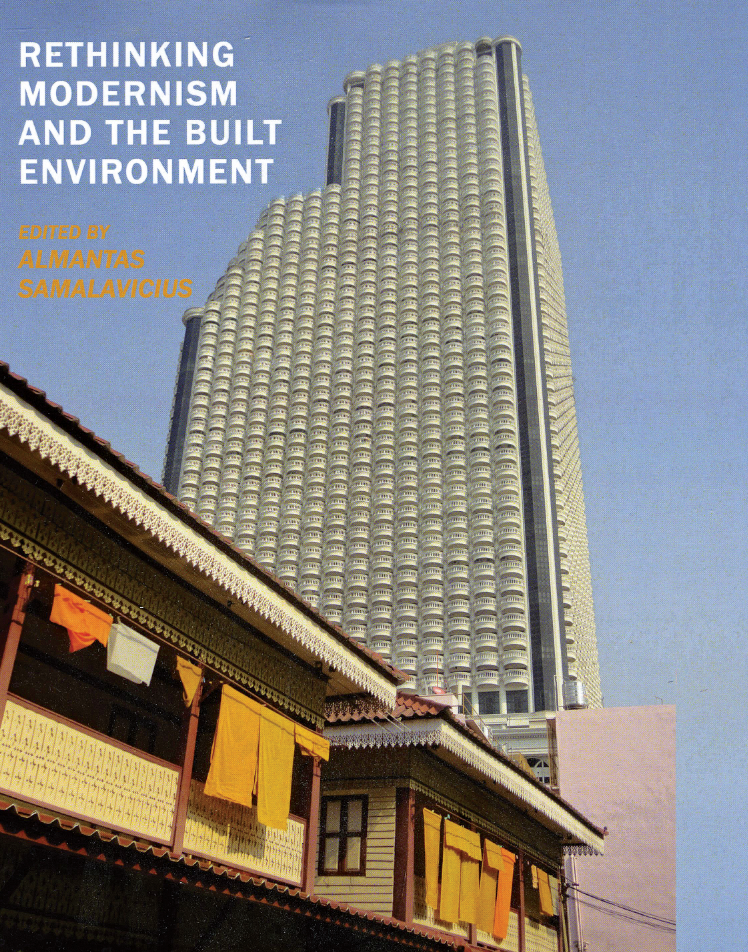

Book Review: Rethinking Modernism and the Built Environment

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Nothing gets old quite so fast as the latest trend. Among the first wave of books to view Modernism and buildings from the mid-20th century in the rear-view mirror is Preservation of Modern Architecture by Theodore H.M. Prudon, a 2008 work that is already a classic. Recently, I had the pleasure of hearing Dr. Prudon speak, and he stressed that the point to remember about modern architecture is that, since its heyday, building technology has changed and continues to change.

Change is also central to the latest addition to the shelf, Rethinking Modernism and the Built Environment, edited by Almantas Samalavicius—not in technology but in perspective. Rethinking is the operative word here, and this book picks the brains, so to speak, of a wide-ranging panel of architects, scholars, authors, and urbanist visionaries to examine Modernism not through individual structures but their collective impact on cities and urban environments as seen from half a century’s distance.

As Samalavicius sets up the premise,“Dissatisfaction with a growing number of the essential aspects of contemporary modernist architecture ... especially with planned urban design during the last century, seems to be shared in various locations of the globe in recent decades.”

Sound like the makings of an eye-glazingly abstract and academic read? Perhaps, but after skimming a few pages, this tidy little tome grows on you— even for the lay student of cities, which means anyone who’s gotten pleasantly lost in an older downtown.

A collection of 23 essays, each chapter is actually a transcribed conversation with Samalavicius that’s kept interesting by its brevity and the often-prickly opinions of the interviewees. In fact, the book is useful just as an international Who’s Who of urban thinkers and opinion makers. The essays cannily start with Witold Rybczynski, the architect and University of Pennsylvania professor who, though books like Makeshift Metropolis, is among the most popular architectural writers on the American scene. Of course, there’s Leon Krier, the Luxembourg-born intellectual light of the New Urbanist movement, as well as the always provocative American author and social critic James Howard Kunstler. The line-up extends well beyond America, Europe, and the English- speaking world; Samalavicius himself is a historian and professor of architecture at Vilnius University in Lithuania.

Well, it should be global. As Samalavicius sees it, the challenges cities face are not only “unprecedented levels of urbanity,” but the homogenizing effects of “economic globalism” and how they have reduced or erased local and cultural diversity. Moreover, this is not a new, 21st-century phenomenon. The large-scale reconstruction of Europe after World War II, he says, “demanded cheap and functional buildings, and that was what architectural Modernism seemed to be able to offer.”

It was also what the building industry was only too happy to supply. The Soviet Union bought in readily too with their own strain of Cold War Modernism—as a-cultural and a historical as it was expedient—leaving its mark across Eastern Europe in ways Samalavicius regularly shows through his first-hand photos and experiences. The net result, as summed up by Nikos Salingaros, author of Principles of Urban Structure, is that “By removing urban complexity, the simplistic Modernist model has destroyed our cities.”

Surprising to this reader, it is not the Bauhaus mafia of Gropius, Mies, and their ilk who are singled out as whipping boys for the urbanist failings of Modernism, but the Franco-Swiss architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, aka Le Corbusier. In more than one essay, Corbu gets called on the mat for being dogmatic and pushing the manifesto of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture). Kunstler, never one to mince words, calls him “a notorious idiot.”Even when built after his passing, Corbu still gets blamed for being the inspiration behind “non-places” such as Brasilia. (One wonders if he’s secretly smiling at all the fuss he’s still causing.)

It’s hard to get through a book of this scope without invoking the names of legendary urbanists, and Jane Jacobs, Lewis Mumford, and even Frank Lloyd Wright all pop up here and there. Ebenezer Howard, the 19th century Brit writer who is the godfather of the Garden City movement—some say all modern urban planning—gets his due, especially from Rybczynski, who points out that Garden Cities took root all over the world, Forest Hills Gardens in New York being only an illustrious American example.

Other essayists are not fans, noting that the Garden City model, based on ample, turn-of the-20th-century greenspace with rails as its lifelines, was trickier to pull off in later economics and could not account for the auto- mobile culture or cheap energy of the post-World War II building explosion.

Rife with sharp thinking and in-your-face pronouncements (Was budding astronomer Carl Sagan really part of Cold-War research to blow up the moon?), Rethinking Modernism and the Built Environment is nothing if not evidence that a lot of smart people are intensely interested in an urban world that has changed and continues to change.

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.