Profiles

David M. Schwarz Architects’ Eclectic Portfolio of Styles

As the saying goes, “discipline is freedom” – the mastery to do whatever you desire – and one thing that’s immediately clear about David M. Schwarz Architects is that this is a firm well-equipped with historical discipline. Just glancing at their portfolio shows not only a varied range of projects, from concert halls to retail spaces to museums, but also a surprising diversity of styles and designs. Though often channeling an earlier era – sometimes even evoking a bit of déjà vu – no building is a mere re-creation of the past, and no two are alike. To find out what’s behind a firm that shifts so fluently from one architectural language to another, I had the recent pleasure of visiting their office in downtown Washington, DC.

Beyond a Single Style

While some architects may have heeded Louis Sullivan’s call to develop their own unique and novel styles, not everyone is content with such a single-minded goal. “The reason our project types are so complex and diverse,” announces David M. Schwarz, AIA, president and LEED AP, with self-deprecating humor, “is because I have a short attention span.” He goes on to explain that after working on block after block of vintage row houses during the early years of the firm, which began in 1976, he would be incredibly bored if he ever again had to do one building type over and over. Schwarz also takes to heart the notion that a good designer can design anything. “We’re constantly restless,” he says, “constantly looking for new answers, different things.”

The proof is certainly in the project list. After cutting its teeth in the historic districts of Washington, DC, in the 1970s, David M. Schwarz Architectural Services, as the firm was then known, began applying the experience they absorbed working on seasoned streetscapes and neighborhoods to designing new construction, but with a historical point of reference. “We’re neo-eclectics,” announces Schwarz, “and we’re proudly eclectic,” clearly not shy about using a label that had its sting in the Modernist 1950s and ’60s. “Most of our work is based in history, and the history of architecture – but we’re not traditional architects,” Schwarz explains further. “In fact, we do some buildings that are quite modern.”

Adds principal Thomas H. Greene, AIA, LEED AP, “We also go beyond eclecticism. It’s really the principles and forms that make traditional architecture interesting; we’re intrigued by the way elements like belt courses and cornices can manipulate the impression that you get from a building.”

A look at some of the firm’s mixed-use urban projects illustrates what he means. In Frisco Square, TX, for example, strong belt courses and cornices bring railroad-era familiarity to a block of brand new brick buildings, while they help define the four stories in human, pedestrian proportions. Eclecticism aside, such handling is one of the firm’s hallmarks. “While our buildings are stylistically enormously diverse,” say Schwarz, “somebody versed in architecture would recognize our buildings as ours by the way we ornament and detail them, by the way we use scale.”

Details and Motifs

So then, how does a firm that claims neo-eclecticism as part of its stock-in-trade avoid slipping into cut-and-paste architecture – that is, merely reshuffling and assembling details and ideas from the past? One answer is by paying attention to what surrounds the project. “We’re serious contextualists,” explains Schwarz, “very concerned about the context in which we’re building, and how our buildings enrich and extend that context, yet still fit in.”

Details are part of what makes that happen, according to the partners. Whether it’s re-creating the spacing rhythm of 19th-century row houses in a city block, or picking up on vernacular building features, such as brick corbels, the firm makes a point of architecturally ‘doing as the Romans do.’ “We try to find the forms that are appropriate for a particular building on that site at that time,” says Craig Williams, principal. “It’s more interesting and it makes the building more personal to its location.”

Another answer is being creative – even highly original – within an eclectic idiom. “We’re enamored of the Classical language,” says Greene, “and we use its grammar, but with our own cornices and other details – our own words, so to speak – that we’ll invent for a specific project.” Adds Williams, “You can’t peg any of our ‘Classical’ style building designs as being, say, academically Tuscan or Corinthian, but they borrow things from past styles that make them well-proportioned, give them a pleasing ratio of solids and voids, make them comfortable for people.”

A case in point is the quintessential feature of the Classical vocabulary: the column. Says Williams, “We like to invent our own family of columns when we get a chance.” A good example is theSchermerhorn Symphony Center in Nashville, TN. Fitting for a city known as the Athens of the South, the Schermerhorn Symphony Center has its own style of column capitals that at once look to the Greco-Egyptian details devised in the 1840s by William Strickland, architect of the Tennessee State Capitol, as well as to the industrial sleekness of the iPod age. It’s no surprise either that the columns also remind some visitors of the ornately topped smokestacks on the steamboats that put Nashville on the map.

“Our buildings are a Rorschach test for a person’s history and experience,” says Schwarz. He recalls how people have told him that a stadium project in Texas resembles a Roman aqueduct, or a building from Boston – or even from Rice University with its Byzantine-style campus. “If there’s enough richness to a building that people can identify their history with it,” he says, “then they have an emotional involvement.”

Indeed, involvement is another touchstone for a David M. Schwarz Architects design. “We want our buildings to create an emotional response,” says Schwarz, “not an intellectual one.” Making his point even clearer, he adds, “We don’t care if a building ‘thinks well’; we want it to feel good.”

Sounds convincing, but how exactly do you get bricks and mortar to stir up thrill or pride? Using details or motifs that represent a place or subject – what the partners call iconography – is a standard method. “We’re fascinated with the use of local iconography,” notes Williams “as a way of making a building of its place.” A favorite source of local iconography is horticulture, like the stylized state flowers used as motifs in the Schermerhorn Symphony Center.

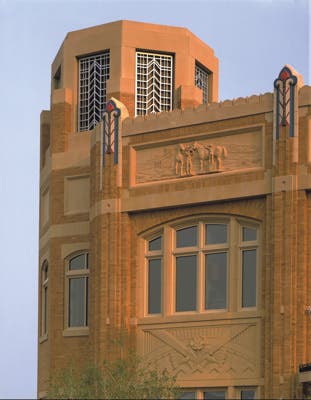

One of the more interesting puzzles was coming up with the right iconography for the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth. Part of a campus of cultural buildings that includes famous local art museums, this 2002 building emulates the 1930s ‘Texas Deco’ used by architect Wyatt Cephas Hedrick in the nearby Texas and Pacific Railroad Terminal. A unique theme for the museum, however, was not so obvious. After much discussion and research, the solution was to create a motif based on the wild rose and incorporate it, among other places, in column capitals with horses.

But where do you turn when a city has no distinguishing iconography – or, perhaps worse, an overload of iconography? Such was the case in designing the Smith Center for the Performing Artsin Las Vegas. “The search for indigenous architecture in Las Vegas is nearly impossible,” says Schwarz, “so the source of iconography became the most indigenous – and longest lasting – piece of human structure within a 100 miles: Hoover Dam.”

The center plays off the Art Deco styling and industrial monumentality of this 1930s landmark. True to form, the firm’s use of iconography has a practical side as well. Says Schwarz, “Local iconography is part of the process of getting the community and the client excited about their building – it’s part of the buy-in.”

Go West Young Architects

Not surprisingly, the restless curiosity of the architects goes beyond the drafting table to a deep interest in the business model of an architectural practice itself. Schwarz, who studied under and worked for the acclaimed postmodernist Charles Moore, recalls a telling early experience. “When I graduated, I asked Charlie, ‘What’s your one piece of advice for me?’ and he replied, ‘If you ever open an architecture firm, make sure you don’t go bankrupt!’”

Schwarz smiles remembering that he laughed at the time, but in due course he realized the extraordinary depth of Moore’s counsel. “It became perfectly clear to me,” he says, “that specializing is not only a bore, it is also a bad business move, because there are cycles in housing and building like everything else.” That revelation has been a cornerstone of the office to this day. “We have been very careful to try and build a firm where our diversity of project types protects us in one way,” he says, “and geographical diversity protects us in another.”

That quest for geographic diversity is what brought David M. Schwarz Architects to Texas. “There’s a longstanding myth that Washington, DC, is recession-proof,” says Schwarz, “but we never believed it.” From the Cook Children’s Medical Center in 1985, with its nod to early-20th-century Classicism, to the striking façade shifts of the Maddox-Muse Center, the firm has enjoyed a characteristically wide range of commissions in Fort Worth – and vice versa.

Here, the firm’s restless creativity comes through again in a tale about one of their seminal Fort Worth projects, the Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass Performance Hall. Commissioned by long-standing clients, the Bass family, the hall is a favorite of the city and firm alike, in no small way due to its imaginative use of imposing, 48-ft high limestone angels at key corners.

“People hire us to do performing arts designs because they love Bass Hall,” says Williams, “but we don’t ever want to do another Bass hall.” In fact, potential clients from Las Vegas once pressed them to simply duplicate the hall in their city. Recalls Greene, “We explained that we can’t reuse that design, but we can use the same attitude, and then come up with something that’s just as appropriate for your city as we did for this city.”

The reluctance to simply rest on the laurels of a good design is not the architects’ only uncommon take on their practice. “One of the founding principles of this firm,” says Schwarz, “is that we view architecture as a service business. Our job is to serve our clients. We most frequently ask clients what to do – not tell them what to do – then we give them a series of choices that is within their realm of desire.”

In the firm’s view, architecture should also serve the public. “We’re very concerned with humanistic architecture;” he continues, “we’re very concerned with places and people; we’re very concerned with community; and we’re very concerned with populism.” Schwarz adds that they’re strong believers in pedestrians too. “For example, years back I set a career goal to create pedestrian environments in Texas – a place where everybody drives everywhere.”

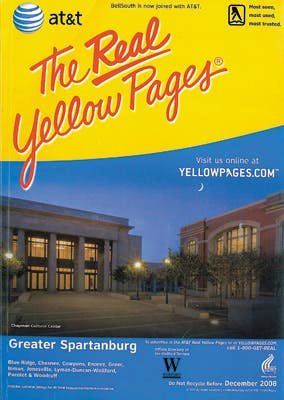

In this light, what starts to become clear is that the restless creativity of David M. Schwarz Architects, is not an end in itself but the means to a larger end: a firm body of work that explores new models of urban design. “Most architects care whether they win architectural awards,” says Schwarz, “but we care about what people see on the front page of phone books.”

When asked to explain the connection, he elaborates with another telling insight: “When a building of yours ends up on the front page of a phone book, it means the community has embraced it, and sees it as a symbol of themselves. We want our buildings to be seen as those symbols.” To that point he notes the several framed phone book covers that share front-office space with an original Frank Lloyd Wright drawing. “We’re honored by the awards too,” quips Schwarz, “but they’re out back.” TB

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.