Features

Book Review: Rescuing Ralph Walker from Oblivion

Ralph Walker: Architect of the Century

by Kathryn E. Holliday

Rizzoli International Publications, New York; 2012

160 pp; hardcover; more than 125 b&w and color images; $50.

ISBN 978-0-8478-3888-2

Reviewed by Clem Labine

Perhaps you, like me, were unaware of the career of architect Ralph Walker. The fact that Walker, a pioneer of the Art Deco skyscraper, is relatively unknown today is amazing considering that the American Institute of Architects, in conjunction with its 100th anniversary in 1957, awarded Walker its Centennial Gold Medal, and the New York Times called him "the architect of the century." Even more amazing: On that occasion Frank Lloyd Wright – a man not known for praising other architects – called Walker "the only other honest architect in America." But even as Walker was basking in the praise of his colleagues, forces were at work within the profession that would soon render Walker's name merely a tiny footnote in the history of 20th-century American architecture.

Remedies for that injustice are now underway. This volume by Kathryn E. Holliday was published as part of a retrospective exhibit of Walker's work held in New York City earlier this year. The exhibit was mounted in a former Bell Telephone building designed by Walker – and which is now renamed Walker Tower by the developer who is converting the building to 50 condominium residences. Holliday's book is a beautifully presented and well-written introduction to the life and work of a man who radically changed the Manhattan skyline in the 1920s and '30s.

Born in 1889 in Waterbury, CT, Walker did not immediately go to college after graduating high school. Instead, he apprenticed in 1907 to Providence, RI, architects Hilton & Jackson. In 1909, Walker began attending classes at the School of Architecture at MIT – where he was exposed to the Beaux-Arts curriculum then in use. However, he left shortly before graduation in 1911 to return to work full time. Walker bounced around among several architectural offices until 1917 when he enlisted in the Camouflage Section of the Army Corps of Engineers.

Returning from WWI in 1919, Walker made a choice that shaped the rest of his career: He joined the office of McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin – an architectural and engineering firm that had clients in the newly burgeoning telephone industry. Walker was hired as chief designer in the hopes he would make the firm's architectural designs as innovative as its engineering work. Walker saw himself as the firm's "analyst of beauty" and gained recognition for masterful handling of form and ornament.

The Barclay-Vesey Building Started It All

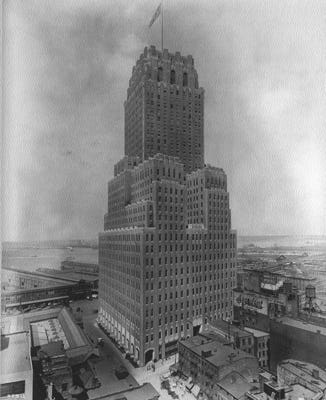

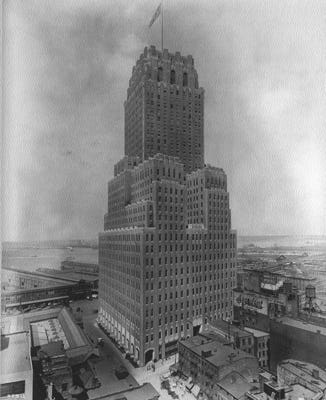

The Barclay-Vesey Telephone Building (now the Verizon Building) in lower Manhattan on West Street overlooking the Hudson River was the project that established Walker's reputation. Completed in 1926, the massive building was intended to consolidate telephone operations as well as project a glamorous forward-looking image for the company. The building had to conform to the new 1916 "sunshine" zoning law that required tall buildings to "step back" to provide light and air to the street below. Walker's asymmetrical solution was revolutionary at the time (see photo) and avoided the monotonous predictability of many of the step-back skyscrapers that followed.

During the 1920s, Walker went on to design numerous tall buildings in Manhattan – most for the Telephone Company. Many of these became landmarks of what was later called the Art Deco style. Unfortunately, the Great Depression put an abrupt end to skyscraper projects. When skyscraper construction resumed after WWII, fashion had shifted away from brick and stone envelopes to the plain glass curtain wall – a type of building that Walker always opposed on aesthetic and functional grounds. He spent the balance of his career working mainly on low-rise suburban industrial parks, planning projects such as two world's fairs, along with active involvement with the AIA.

Ironically, an image of the Barclay-Vesey Building was used as the frontispiece of the 1927 American edition of Le Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture. Walker's use of sculptural shapes and ornament was definitely not the type of architecture Le Corbusier had in mind. And it was Walker's later railings against the sterile International Style that got him excommunicated by the Modernists from 20th-century architectural history.

Walker believed an architect should be concerned with beauty, and divided the design process into two parts: First, make the building work functionally; second, make it work "spiritually." He also spoke of "humanist" architecture, and his skillful manipulation of sculptural forms and ornament flowed from his desire to infuse spiritual qualities into his buildings.

Though modern, Walker was not a Modernist – and his insistence that architecture should have a spiritual component made him a vocal critic of the austere, technological designs of Le Corbusier and Gropius. As Modernists gained ascendency in the architectural establishment, however, they fought back with equal vigor – and eventually managed to almost completely erase Walker's name from the 20th-century architectural pantheon.

Holliday's concise text, combined with numerous historical photographs, provide a firm basis for re-evaluating the work of this major 20th-century architectural talent. Ralph Walker certainly deserves better treatment than he has received from those who have been dictating architectural history for the last 60 years. TB