Features

Book Review: Railroad Stations

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Railroad Stations: The Buildings That Linked the Nation

by David Naylor

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York, NY; 2011

336 pp; hardcover; b&w images; $75

ISBN: 978-0-393-73164-4

Reviewed by Lynne Lavelle

From the Art Deco glamour of New York City's Grand Central Terminal to the Spanish Mission styles of Florida, railroad stations are among the most architecturally diverse and culturally rich building types in the country. As the sprawl of railroads brought the country together in the mid-19th century, the lack of a direct model for station development led to great variety in their stylistic character, with many extending beyond their primary functions to become meeting places, venues for impromptu rallies and even actors in historical events. In this latest addition to the Library of Congress Visual Sourcebooks in Architecture, Design, and Engineering series, published by Norton, architectural historian David Naylor's Railroad Stations: The Buildings That Linked the Nation is a fascinating compilation of archival images, plans, drawings and prose, all of which illustrate the unique histories and features of these civic landmarks.

To understand railroad stations, one must of course understand the history and social impact of the railroad.

Railroad Stations begins with "Building the American Railroad," which examines how railroad development influenced pivotal moments in history, from cultural events such as the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition to the outcome of the Civil War. By 1860, American rail companies had laid approximately 30,000 miles of track; that two thirds were in the northern states gave union troops a considerable advantage. And in the post-war period, as the country began to focus on the exploration and settlement of the western territories, new rail lines and stations served as outposts for the frontiers. Progress on this front was swift – the first transcontinental rail line was completed at Promontory, UT, in just five years – and aided by Lincoln's signing of the Railroad Act in 1862.

While the expansion of railroads was a national project, the stations themselves reflected the fortunes and populations of their immediate towns, cities and regions. Noting that "Nineteenth-century American architecture was awash in stylistic revivals," Naylor explains that size and complexity, rather than style, were the main distinguishing factors between the big-city stations and those on the frontiers. The book's images illustrate these contrasts in black and white, grouped together as: Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia; Pennsylvania and Ohio; New Jersey and New York; New England; The South; The Midwest; The Northern Plans and the Northwest; The Central Plains and the Rockies; and The Southwest.

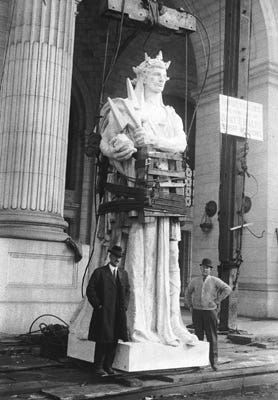

Though many of these stations survive, some were abandoned or lost to development. Of the latter group, New York City's demolition of Pennsylvania Station in the mid-1960s to make way for Madison Square Garden was perhaps the most contentious – so much so that it helped begin the national preservation movement. The many turn-of-the-century photographs of Pennsylvania Station's latticework roof, magnificent waiting room and columned façade still provoke outrage, particularly when paired with sad details, such as: "In an infamous turn of events, the eagles fronting the top of the main entry pavilion were exiled to the wetland refuse tip in New Jersey during demolition of the station."

But as Naylor explains, things could have gotten much worse, as Grand Central Station was also on the newly established New York City Landmarks Commission's chopping block for being too small. It was, of course, spared and enlarged in 1898, and the current building opened in 1913.

Among the most interesting archival photographs are those from times of turmoil. A crowd gathered outside Grand Central Terminal to watch the television coverage of President Kennedy's funeral in 1963; soldiers headed to Europe from Pennsylvania Station in 1942; President Lincoln's funeral car in Alexandria, VA, in 1865; and Roosevelt's Rough Riders' arrival in Tampa, FL, in 1898 are a reminder of just how important railroad stations were and are – "What all these stations had in common for the first century of the railroads was a sense of their centrality in the communities they served," writes Naylor. Railroad Stations captures the versatility of their design and the endurance of their appeal.