Features

Q and A with Gil Schafer

The room had the happy buzz of a family reunion, filled with a long, warm conversation about a shared past and a bright look toward the future. Just weeks before, the architect Gil Schafer III had merged with Buccellato Design, two prestigious firms with many awards for contemporary classical architecture. The new firm, Schafer Buccellato Architects, brings home the long-held intentions of the architects to meld and grow together, embracing a new spirit while retaining the foundation of the past.

The similarities in the lives of the three design partners–Schafer, Aimee Buccellato, and Kevin Buccellato–are abundant. (Lou Taylor, who runs the financial side, is also a partner.) All three were drawn to architecture and construction as children, have lived in many different settings and styles of homes, and realized early in life the role of houses in helping individuals thrive.

More than 20 years ago, Aimee Buccellato was the first staff member of G.P. Schafer Architect. Kevin Buccellato, her husband, also joined the firm and worked closely with Schafer at the same time. Those years, Kevin Buccellato says, were about “building a culture of nurturing, mentoring, and learning.” All three architects vividly recall that period in the early 2000s, when they collaborated on the design of residences in the Hudson Valley in New York, all rooted in American vernacular. “It was a model way to learn in the trenches: fun and exhausting, but fulfilling,” Aimee Buccellato says.

In time, the couple relocated to South Bend, Indiana, where they balanced an architectural practice with parenthood and professorships at the University of Notre Dame’s School of Architecture. As the years passed, many of the Buccellatos’ students went to work for Schafer in his longtime headquarters overlooking Union Square in New York City, now the home of Schafer Buccellato Architects.

All three design partners hold lifelong learning close to their hearts. As Aimee Buccellato says, “life can feel very episodic; but we don’t live in vignettes. This work requires a lot of patience and consideration. We want young people to be proud to be part of a legacy of craftsmanship.” When Schafer demurs at being called an educator, she disagrees: “Gil is a top educator, his work is rooted in lifelong apprenticeship.”

For his part, Schafer, the grandson and great-great-grandson of architects, firmly believes that the close, nurturing alliance of generations in architecture is key to success. “To always learn and improve, you have to be open to the energy of those around you,” says Schafer, who has published three books and is one of the country’s brightest lights in classical architecture. As Schafer mulled his long professional path in recent years, as the Buccatellos shifted out of academia, the trio began to play with a special notion that has animated so many successful mergers: “Maybe we could grow together.”

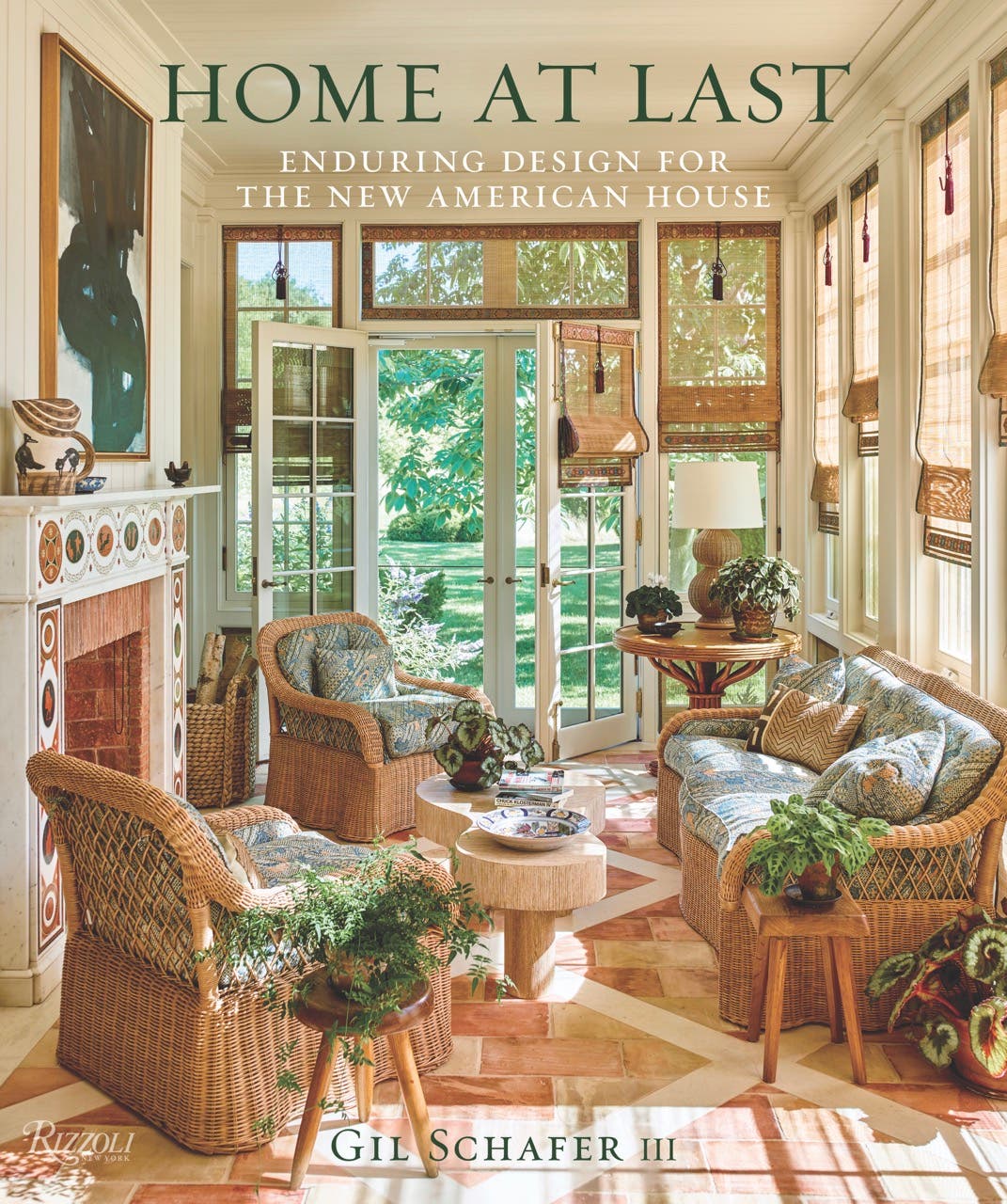

Here, Gil Schafer talks about the importance of growth, mentorship, and learning, and his newest book, Home at Last (Rizzoli), debuting in spring 2024.

Tell me about your new book, Home at Last, which presents your work and explains your design philosophy.

Home at Last is the third in a three-part series looking at my work over 20 years. My books have always been personal, and this one shows how houses can change and evolve with life. Clients talk about these houses as being their “forever homes,” places of quality, places that are often generational homes. I’ve learned that houses have to evolve with the lives of the people in them. I always say that we’re in the joy business; this book is about that journey.

Your great-great-grandfather and grandfather were both architects. You must have known, at an early age, that you would be one, too. In your second book, A Place to Call Home, you talk about how the places you lived as a kid influenced your design sensibility. Tell me more about this.

I was born in Ohio and then lived most of my childhood on a farm in rural New Jersey. My parents divorced, so I also moved around a fair bit. All the places we lived were very different, which I paid keen attention to, probably because I had that genetic wiring to be an architect.

You have designed houses and renovations all over the country. Do any of these projects stand out as particularly memorable? Why?

The memorable projects are usually the ones that challenge us in some new way. If I’m not a little scared by a project–by its challenges–I get worried. We just restored a landmarked boathouse in Maine from the early 1900s, originally built for a 100-foot steam yacht, something that we’d never done before. We had to make a building that is half in water and half to live in. It was technically and aesthetically very challenging–but thrilling.

What advice do you give emerging professionals in the architecture and interiors field?

In the age of short attention spans, speed viewing, and Instagram, it’s crucial to look slowly, to take time to study. I think there’s a bit too much of the glance-and-swipe today. It takes time to look deeply, and learn from history. It’s important to take that time.

Most architects write a book because it’s good PR. But my sense is that it’s more than that for you; you are at heart an educator. This is certainly evidenced by your early involvement with the ICAA, a classical education institution. Now you have written three books which do much more than show your firm’s work.

How do you come by your willingness to teach?

I’m not a bona fide teacher like Aimee and Kevin, but I had great mentorship at Ferguson & Shamamian Architects [in New York City] and elsewhere and learned that way. People were so generous with their knowledge with me. I realized that it is important to do the same. The more I know, the more I recognize I need to learn. It’s about humility. If you think you know it all, there’s nothing left to learn. TB