Features

Postmodernism: A Look Back, and Ahead

By Martha McDonald

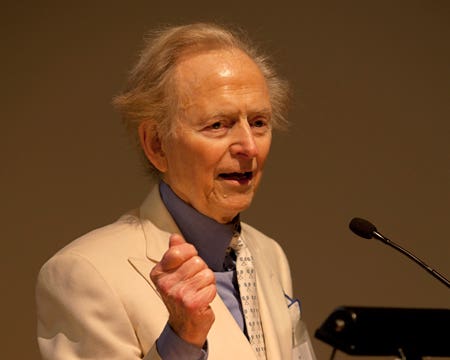

More than 400 architects, educators, preservationists, journalists and others turned out on Veterans Day weekend in November to hear what a long list of architectural luminaries had to say about Postmodernism. Organized by Gary Brewer, partner, Robert A.M. Stern Architects, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art (ICAA), the conference was held in New York City's CUNY (City University of New York) Graduate Center on the 30th anniversary of the publication of Tom Wolfe's From Bauhaus to Our House. Wolfe himself was the keynote speaker.

"Postmodernism is to theory what the 1957 film classic, The Three Faces of Eve, is to the canon of Hollywood. It is a story about a multiple personality disorders, or as we now say, dissociative identity disorders," said Paul Gunther, president of the ICAA, kicking off the event. He added that the definition is subjective and that Postmodernism's identity ranges from all that is reactionary, to all that is liberating, to scholarship. "It is Las Vegas as opposed to Berlin. It is an environmental wake-up call for rediscovering traditional architecture and it is humane. On the other hand, it is bad theme park. When all else fails, say postmodern, no matter what your point of view."

Postmodernism is considered the traditional polemic divide between Modernists and Classicists, Gunther continued.

Gary Brewer introduced the conference, noting that Postmodernism has been considered "the gateway drug to tradition," adding that "Veterans Day was designed to perpetuate peace between nations and … architectural camps."

Dr. Richard John launched the program, noting that it has been widely reported that, according to Charles Jencks, who invented the term Postmodernism, that Modernism ended on July 15, 1972, at 3:32 p.m., with the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project. Actually, he continued, it wasn't all that neat. "The decline of Modernism shows that the seeds of its failure were sown at the very beginning."

From there he and others traced Modernism from its beginnings in Stuttgart in 1927, through the International style embraced by Le Corbusier, Mies Van Der Rohe and Walter Gropius, to the 1967 exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) featuring five Postmodernism architects. In the meantime, critics began to speak out against Modernism. These included Jane Jacobs in Life and Death of the American City (1961), David Watkin who said in Morality and Architecture (1977), "This new style of the 20th century is totalitarian," and Tom Wolfe.

Postmodernism, Dr. John said, began with Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown (authors of Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 1972) and included others such as Allen Greenberg, Michael Graves, Thomas Gordon Smith and Robert A.M. Stern, who "left behind Modernism and embraced humanistic architecture of color and form." In conclusion, he noted that while Postmodernism has been given a bad name by many, it can provide a built environment of extraordinary humanism and vitality.

Also setting the scene was Robert Adam, who reviewed the social and economic situation of the time. "Artistic movements don't pop up out of nowhere," he said, noting that they emerge because of social and economic events. "Architecture is just a part of those events, and in the end a minor part."

"The more orthodox traditional movement is the only survivor of the Postmodernism period," Adam noted. "Post-modernism is surviving in the Far East," he concluded. "The economic and political axis is moving east." In his keynote address, Tom Wolfe – dressed in his signature white suit and shoes – said: "Modernism was a 'slave rebellion' in architecture, where the architects began to dictate to the clients, rather than the other way around."

He traced its origins from the compounds in Europe after the First World War to triumphs in the U.S. after WWII, noting that there are still architects today who are bound to Modernism as a pure form. From there, various speakers and panels discussed topics such as before Postmodernism, architectural education, Postmodernism and the media, looking back, Postmodernism reconsidered, Postmodernism and urbanism, 105 orders of architecture, the return of tradition, the ironic imperative of Postmodern architecture, and finally, the aftermath. Recorded interviews with Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi and Vincent Scully were also presented. Here are some of the comments made during the presentations:

Michael Lykoudis: We have created a second America since WWII and this second America is ugly. We have created a physical world that has no joy or energy. We have destroyed both the city and the country. It's the profession's greatest challenge – to turn that around.

Jaquelin Robertson: About the time I was going to graduate from Yale, I had the opportunity to get a Rhodes scholarship, but they didn't teach architecture. I went anyway and it was the best education in architecture that you could get. Oxford was a staggering eye opener, to see urbanism and buildings. Cities are made of buildings and cities and buildings are one and the same – and you can't take them apart. Yale hadn't gotten that idea yet.

Thomas Beeby: Postmodernism tried to transform the Classical orders and apply them to modern architecture. Living in a good urban culture is so important to architectural education. The fabric of the city lets life happen.

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk: The introduction of the word "urbanism" was just occurring when I was in architecture school. It did not become an important issue until the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies brought over architecture from Europe, and taught about urban cities. Looking back, they all hang together. The notion of lasting value is very important. Architecture is a language. Gehry is very talented, but it is hard to work in his language.

Paul Goldberger: You always hear the music that was playing when you first walked into the dance, and for me that was Charles Moore, Venturi, Graves and so forth.

Mildred Schmertz: We weren't the architecture critics. We saw ourselves as reporters and journalists. There is a big difference. It is an entirely different game. Our job was to find the best work available and understand and support it. The architects were doing the architecture, we were writing about it. There was so much energy and vitality in this emerging young group. They were making architecture and we were showing it, so I think the magazines played a very important role in showing the best work.

John Morris Dixon: We were journalists, not critics. We were trying to interpret, not necessarily critique the work. We were covering the emerging talents, emerging trends. I was skeptical of the Modernists' idea of social commitment. We hear it again today. I really think the designers of Modernism were very much aesthetically motivated. Also there's the question as to whether exposed steel and exposed concrete did anything socially for the masses. It wasn't a social medium.

Robert Campbell: I don't care what style a building is. I think you can do a good building in any style. It is not the responsibility of a critic to push a particular program. We are all going to have to live with the fact that we live in a culture where there are lots of different kinds of architecture and styles going on at the same time.

Michael Graves: All of these things were pouring in and life was getting a lot richer. I thought that Modern architecture's emotional state, from A to B, was not enough. I wanted to make an architecture that was broader. It was a very big struggle for me. Little by little I changed my style.

Andrés Duany: My experience as a student was that Postmodernism was about scholarship and the recovery of knowledge. It was fun because it was so radical. At one point, Bob Stern was the most radical and avant garde architect on earth. It was about scholarship, about books, about recovery of the lost knowledge.

Barry Bergdoll: I have been perplexed all day wondering whether I am at an event about the continuity of something that began 30 years ago or whether we are looking back at an event that is over.

Robert A.M. Stern: Postmodernism is actually 50-60-years old. In the 1950s, some people – not many, but a few – had a wake up call, a reaction to the Modernist impact on our cities, the destruction and what was replacing the destruction. As an architecture student in the 1960s, looking out of the window on the top floor, looking north across the campus of Yale, one could see Gothic buildings built as early as 1840, and one could also see superb buildings built 1920-1940. As a student we were marinated in the Modernism. It was not just a style. It was a sense of loss that needed to be recuperated in the culture. For one time in the history of man, architecture may have been the leading indicator of a cultural malaise. It's a style and it's an attitude, and we are all postmodernists, even if we went to Notre Dame A fundamental problem we have in architecture at the moment is that human proportions are not pixelated quite right.

David M. Schwarz: I don't think there is a clear distinction between Postmodernism as a style or as a period in time. There was a period in time when something called Postmodernism reigned, where details were where they were supposed to be, where colors were brighter, where everything was more so. I think that is incidental to Postmodernism. My firm started in 1976. We are postmodernists – we also call ourselves neo-eclectics, in that we are a reaction to a period of time called Modernism.

It is important to see what has evolved from that revolution. Many of us have evolved greatly from that point, and have learned a great deal from rejecting those narrow principles of Modernism.

The promotion of dogma is rather dangerous. All of us, on both sides of the argument, fought for great buildings in a better world. I find it distressing that we all think that we are right. The thing that makes cities wonderful is diversity. Because we have been so busy fighting with each other, we distract ourselves with quite meaningless conversations and the result is that our environment gets much worse on a continuing basis.

Postmodern urbanism is still urbanism. Most modern urbanism is 19th-century urbanism with the addition of the automobile.

Andrés Duany, presenting his 105 architectural orders: The project began with a kind of fury at what Palladio had left out when he wrote his four books. Palladio wrote what is essentially a professional brochure, very similar to Complexity and Contradiction in Modern Architecture. The problem is with the people who say this is the one and only way that you do it. A great number of people think that Classicism is the only way to work. I felt that a lot had been left out.

Robert Adam: My great hope at the time was that a lot of people would actually pick this [Postmodernism] up and deal with it in an original way and carry on, and my great disappointment was that it settled down into battles – straight practitioners on one side and people who dropped it like hot coal on the other. The polarization that took place quite savagely in the 1990s is very boring, and I hope this new generation will stop this. It stops people from doing things. My hope is that in the future we have a more open system. Tradition is rather like evolution. You can always trace your way back to the ape. If you actually innovate where you are not passing that on, you have lost that connection and you have broken tradition. That's the test. If it is a tradition, you have to be aware of its origins.

Thomas Gordon Smith: It has been said that Postmodernism died, but many of us found a direction toward Classicism and the rationale, which was important at that time, to resist negative pressure, to continue to less ironic approaches. My sense in my own personal development is that I had two paths. One would have been continue with this art with the same sort of jokes because they work fine. I made the effort and decided to follow a path that would call for more integration.

Peter Pennoyer: We frankly had a huge amount of learning to do [about Classicism]. In my first project, I confess I had one column shaft without the base or the cap, with a ¾-in. reveal above and I set it against a Corbusian wall which we called the potato. It was a long learning curve. It involved relationships with colleagues like Gregory Gilmartin, studying books, travel, drawing, photography; it took a lot of study and patience.

Charles Jencks: Modernization, modernity and Modernism come together as a package. As long as Modernism is around as the reigning discipline, there will be loyal postmodernist opposition, sometimes disloyal. Postmodernism in that sense will last for the next 100 or 200 years, as long as the Modernist agenda is in the driver's seat.

That is based on the fact that half of the world lives in cities and the other half in the countryside. That part that isn't urbanized is still trying to modernize. This is why it is a long-term proposition. All the other isms became was-isms quite quickly. Postmodernism keeps coming back, as Modernism does. They won't go away even if we hate them. Postmodernism is very much alive. It exists in 40-50 different fields, such as art, dance, literature and so forth.

On Classicism:

Robert Adam: Classicism is a language and if you speak the language clearly, then you know straight away if someone else is speaking it correctly or not.

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk: Classicism is a very good language. The idea is that it gets better as it goes along. Trying to develop one of a kind doesn't have the idea that things are going to get better.

Demetri Porphyrios: Any society that does not produce robust buildings, which are meant to outlive the people that produced them, is of no interest to history or to mankind in general. It was mentioned before that it is possible that Postmodernism helped the resurrection, the return of Classical values. That is utter nonsense. The two are contradictory. It is a paradoxical statement that Postmodernism can ever assist the Classical.

David Schwarz: I think there is continuum of Classicism which exists outside the realm of what else is happening. The notion is that Postmodernism did permit Classicism, but that doesn't necessarily change the continuum. For a true Classicist, Postmodernism was irrelevant. All it did was give them more opportunities to practice. Classicism is the only style that has existed for 3,000 years – the only style – and it has been reinvented by every generation that practices it. Classicism in its broad sense has been adapted by different generations for thousands of years.

The Future:

Mark Wigley: We are moving toward a population of seven billion people living in cities. We know less about the city of future than we know about what it would mean to live on Mars. That is going to require every skilled mind in our field, also all the other fields. We have yet to discuss the sheer demographic momentum that is rushing toward us.

Demetri Porphyrios: The most fundamental problem we are facing is how are we going to urbanize? It doesn't really matter what the building looks like as long it is a structure around which we can hang our coats and dreams. All of that style will be like icing on the cake. If there is no cake, what do you do about icing? TB

Speakers and Panelists

Robert Adam, architect, author and teacher, co-founder of ADAM Architecture

Thomas H. Beeby, architect, author and former dean of Yale's School of Architecture

Barry Bergdoll, author, professor of architectural history at Columbia and the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at MoMA

Robert Campbell, Pulitzer prize winner, architecture critic for the Boston Globe and a graduate of Harvard's Graduate School of Design

Judith DiMaio, dean of the School of Architecture and Design at the New York Institute of Technology

John Morris Dixon, FAIA, chief editor of Progressive Architecture from 1975 to 1995

Andrés Duany, co-founder of the Congress for New Urbanism, principal of Duany Plater-Zyberk

Ellen Dunham-Jones, professor, the architecture program of the Georgia Institute of Technology

Paul Goldberger, architecture critic of The New York Times for 25 years during which time he won a Pulitzer Prize, currently with the New Yorker

Michael Graves, architect, author and Schirmer professor of architecture at Princeton; recipient of the 2012 Driehaus Prize

Sam Jacob, architect, designer, writer and critic, founding director of FAT

Charles Jencks, historian, theorist and architect and creator of the term Postmodernism

Richard John, historian, author and educator

Michael Lykoudis, dean of Notre Dame's School of Architecture

Reinhold Martin, professor of architecture at Columbia University

Peter Pennoyer, chairman of the board, ICAA, and head of his own practice

Emmaneul Petit, architect, writer and associate professor at the Yale School of Architecture

Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, co-founder of Duany Plater-Zyberk and of the Congress for the New Urbanism

Demetri Porphyrios, writer, teacher, historian, and founding principal of Porphyrios Associates

Nina Rappaport, architectural critic, curator and educator, director of publication for the Yale Schoolof Architecture

Jaquelin T. Robertson, founding principal of Cooper, Robertson & Partners, former dean of the University of the Virginia School of Architecture

Witold Rybczynski, author on architecture, housing, technology, urban design and modern culture, professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and serves on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts

Michelangelo Sabatino, associate professor at the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture of the University of Houston

Mildred F. Schmertz, former editor-in-chief of Architectural Record, where she wrote and edited for 33 years

Denise Scott Brown, (appeared in a video), architect, theorist and planner, principal at Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates

Vincent Scully, (appeared on video), Sterling professor emeritus of the History of Art at Yale

Thomas Gordon Smith, professor of architecture at Notre Dame's School of Architecture, as former chair, he resurrected the study of Classical architecture; founder of his own practice; author

Daniel Solomon, director of his firm, co-founder of the Congress of New Urbanism, professor of architecture at UC Berkeley

Suzanne Stephens, author, editor and critic

Robert A.M. Stern, founding partner of Robert A.M. Stern Architects, dean of the Yale School of Architecture

Martino Stierli, art historian and research fellow at the University of Basel

Charles Warren, architect and author, founder of his own practice in NYC

Gwendolyn Wright, historian, educator and writer, professor at Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture; co-host of the PBS Series, History Detectives

Mark Wigley, dean of Columbia University's School of Architecture

Tom Wolfe, author, journalist and essayist; author of From Bauhaus to Our House.