Features

Passion for the Past

In the last 10 years, as president and CEO of Preservation Maryland, Nicholas Redding has channeled a lifelong passion for the past into a forward-thinking vision for the future of preservation. Since assuming the role while still in his 20s, Redding has led the 93-year-old nonprofit through a period of evolution that included a merger, the creation of Smart Growth Maryland to help counter regional sprawl, and the inauguration of the Historic Property Redevelopment Program, a concerted push to save Maryland’s historic places and adapt them to the present. As he marks a decade at the helm, Redding spoke with Traditional Building about his introduction to the wonders of historic preservation, Preservation Maryland’s national-scale workforce development partnership with the National Parks Service, and what he’s learned through hosting a weekly preservation-themed podcast.

What formative experiences shaped your sense of why historic preservation matters?

Nicholas Redding: It began with stories from my great-grandmother, who was born in 1910, about the Civil War veteran in our family—that excited me as a young kid and began my fascination with history. I learned that we could use historic places to make our world better: We live in a society that has a lot of challenges, and inherent in preservation are opportunities to address some of them, from a changing climate to workforce development to smart community development patterns. A big part of our job is making those connections. Ensuring that everyone sees themselves reflected in the past gives us a commonality and an understanding of where we came from, both good and bad. That’s what keeps me moving forward: not trapping historic places in amber, but making them worthy parts of an ever-changing world.

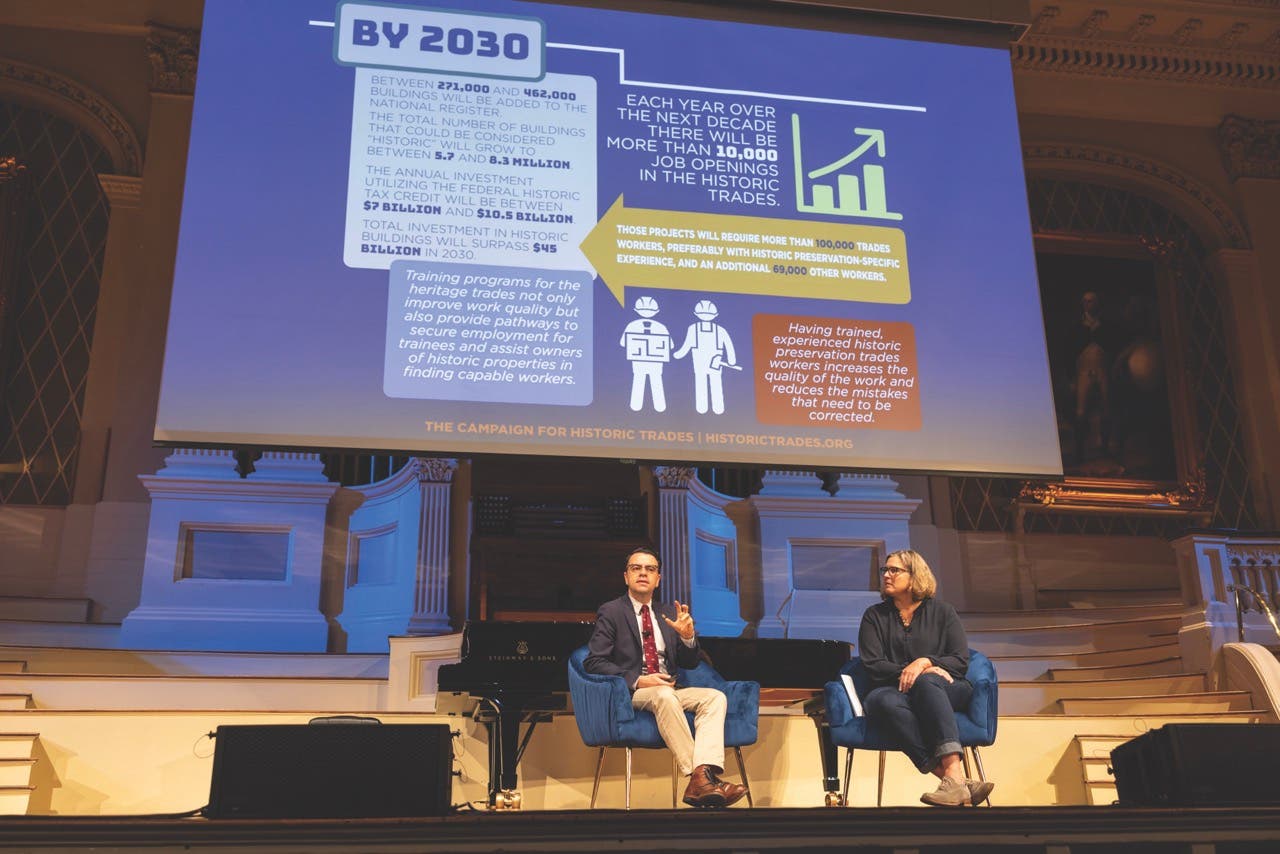

Let’s talk about the scarcity of tradespeople who have expertise in historic preservation and rehabilitation, and how The Campaign for Historic Trades—Preservation Maryland’s partnership with the National Park Service—strives to change the state of things.

Preservation without trained hands to do the work is often just good intentions. And we’re at a real inflection point in the traditional trades community: more structures in the United States are reaching the 50-year mark every year, and there are not enough people to do the work that needs to be done. Preservation trades deserve attention if we’re serious about maintaining these places, and this is a huge opportunity for the national preservation community to put themselves at the center of a conversation about meaningful careers and a workforce in the era of automation and AI. At its best, ChatGPT still can’t reglaze a window.

We’re in a position to partner with for-profits, nonprofits, and public partners all across the country, and we’re fortunate that the stars aligned with Preservation Maryland and the Historic Preservation Training Center, a program of the National Park Service that’s in our back yard in Frederick, Maryland. We’re building out a curriculum that anybody can use. We’re creating registered apprenticeship programs to create more sustainable and straightforward ways for the industry to train people getting into these careers, while at the same time making sure that we have opportunities for young adults and people contemplating a second career to think about how they fit in. It’s a huge job—it’s not one we can do alone, but we want to be the spark that will help build and sustain a movement.

Tell us about some of the recent work Preservation Maryland has carried out at 417 North Jonathan Street in Hagerstown and the Burtis House in Annapolis.

Through the Historic Property Redevelopment Program, we’re showing the general public the value of these buildings and the opportunity that they provide as they’re rehabilitated. Our first big project was at 417 North Jonathan Street, which was a historic log cabin that was reconstructed in the 1830s from timbers felled in the winter of 1739, making it one of the oldest standing structures in the entire city of Hagerstown. There was this long, rich history associated with this building located in an African American community—and, after it had been severely damaged in an automobile accident, it came within a whisper of being demolished. We partnered with community members to invest in the project and rehabilitate it as owner-occupied housing. Some of the contractors [who carried out the work] talked about how often they had been stopped by people walking past, and really being touched by seeing their eyes open to the history in their back yard.

So much of Maryland’s history sits at the water’s edge. The Burtis House is the last remaining waterman’s cottage sitting at the very edge of City Dock, and we partnered with the City of Annapolis, which owns the property, to assist in stabilizing and elevating that structure out of the path of a rising Chesapeake Bay. The Burtis House has very different challenges from Jonathan Street, but the opportunity is the same: to make sure that everyone sees themselves reflected in history, and that that history can survive as places evolve. It’s been said that preservation, at its best, is a conversation between the past, the present, and the future. That’s the sweet spot where we like to find these projects.

You’ve hosted more than 300 episodes of the award-winning PreserveCast. What have you learned by using a podcast to further a wider preservation mission?

Only talking about buildings and cornices and bricks and decorative ironwork does not capture attention: it’s stories, and PreserveCast is a way for us to engage in storytelling and capture a different, international audience. One of the most interesting things about the podcast has been asking how people got involved in preservation. A lot of it starts at a young age when someone shows them that history is cool and interesting to think about. It’s very rarely a straight line, and preservation is a great place where, eventually, people find their way. TB