Features

Book Review: Paradise Planned

Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City

By Robert A. M. Stern, David Fishman and Jacob Tilove

The Monacelli Press, New York; 2013

1,072 pp; hardcover; over 3,000 color and b&w images; $95

ISBN: 978-1-58093-326-1

Reviewed by Clem Labine

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Do you believe suburban sprawl is deadly to both the environment and social cohesion? Well, possible cures are contained in a pioneering new work by Robert A.M. Stern and co-authors David Fishman and Jacob Tilove. Their massive volume (1,072 densely packed pages) constitutes the first comprehensive review of nearly two centuries of the garden suburb movement in Europe and the U.S. – a time in which innovative planners found ways to reconcile cultural benefits of urban life with the solitary pleasures of nature. Even though the successes of those early garden suburbs were forgotten during the second half of the 20th century, the authors contend that those models hold lessons for creating more people-friendly and earth-friendly developments today.

Lest potential readers be daunted at the prospect of plowing through 1,072 pages of text, we should point out that the bulk of the volume – illustrations and descriptions of hundreds of garden suburb developments – is mainly reference material, to be dipped into as needs dictate. The balance of the book is primarily historical background on various strands of the garden suburb movement, such as the garden city, the resort garden suburb, the industrial garden village, the streetcar suburb, etc.

Taking pains to distinguish the garden suburb typology from today’s suburban subdivision, the authors define the garden suburb as a carefully planned community existing in relationship to a nearby city. The garden suburb is built around strong planning aesthetics and social principles, with clear borders and a defined center. Any analysis of a garden suburb plan has to take into account sociology, infrastructure, architecture and landscaping.

For each of the hundreds of garden suburb developments delineated, three types of information are given: street maps and plans, photos of architecture and landscaping (both historic and contemporary), and descriptive text outlining history and prominent features of the village. (One might wish for larger images – but then the book would have been 2,000 pages!) Space devoted to each suburb can range from a paragraph to several pages, depending on the importance of the development to the authors’ narrative.

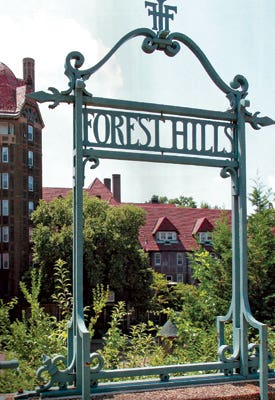

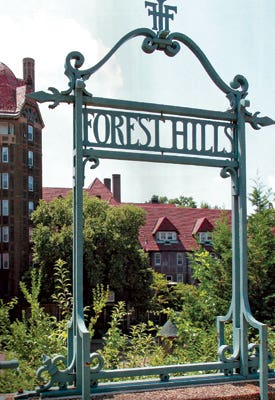

For example, there is a particularly detailed section devoted to Forest Hills Gardens in New York City’s borough of Queens because the authors consider it to be the pre-eminent American expression of the garden suburb ideal. Forest Hills is a semi-self-sufficient suburban village embedded in the largely unplanned matrix of surrounding Queens. A station of the Long Island Railroad, which connects Forest Hills to the center of Manhattan, forms the nucleus of the village. Started in 1909, its sophisticated plan (by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.), diversity of architecturally refined buildings, railroad station, hotel, apartments, shops, grouped townhouses, plus semi-detached and single family residences combine to keep Forest Hills Gardens one of New York City’s most desirable residential neighborhoods.

Paradise Lost and Regained

The building boom after 1945 marks the demise of the garden suburb. By that time, Modernist ideology, with its anti-historical rejection of traditional forms, had captured the imagination of planners. The “towers in a park” theory of Le Corbusier and the Broadacre City scheme of Frank Lloyd Wright became the hot ideas. Wright’s spread-out Broadacre City was automobile-centric – the polar opposite of transit-oriented communities of the garden suburb era – and provided the philosophical underpinnings for frenzied construction of rambling subdivisions that have consumed so much of our countryside.

The book’s Epilogue provides a concise reprise of the troubles visited upon the U.S. as a result of higgledy-piggledy growth. The unlikely hero singled out as a prime mover in putting rational thinking back into urban planning is Walt Disney! Disney’s personal vision for Main Street in the original Disneyland (1955) was the first development to draw attention to the enduring emotional power of traditional urbanism.

A far more developed version of that vision sprang up as the town of Celebration, FL, in the 1990s, which the book describes in some detail since Stern’s firm was involved with the town’s master plan. The book also recounts capsule histories of other developments in the traditional town movement including Seaside, FL, Poundbury in the UK, and the founding of the Congress for the New Urbanism. Many aspects of these new urbanist projects, e.g., transit-oriented development, borrow ideas that originally blossomed in the garden suburb movement.

In the book’s concluding section, the authors assert some intriguing possibilities of the garden suburb and traditional town planning for the modern city. Many older cities, especially in the Northeast and Midwest, contain empty urban wastelands between urban cores and surrounding suburbs. These depopulated areas, which the authors call “Middle City,” still possess their street grids and buried utilities, making them logical candidates for transit-oriented redevelopment with pedestrian-friendly streets, town centers, small yards and expansive public areas – all characteristics found in earlier garden suburb models. For planners and developers attracted to this option, the research compiled by Robert Stern and his associates provides an impressive array of time-tested templates for building better communities.

Clem Labine is the founder and editor emeritus of Traditional Building. He is also the founder of Period HomesandThe Old-House Journal magazines. He is currently an independent consultant.