Features

Pages from a Sketchbook: A Model Street for Cities

By Eric Osth, AIA

In 1924, the poet Pablo Neruda wrote, “forgetting is so long.” He meant that, compared to life and love (which are too short), forgetting has the great danger of becoming permanent and we can lose so many things we value. We cannot afford to forget that great streets can serve as centers of urban life, creating character and regeneration. Sadly, we have rarely tried to understand the power of streets and how they can transform our cities and neighborhoods.

In recent decades, street design has become an awkward byproduct of a number of factors: lack of coordination between design and engineering professionals, and a subscription to the unwelcome belief that streets are only to serve cars and for nothing else. Now, more than ever, it is critical to use streets to comprehensively coordinate the competing technical and qualitative interests of business owners, residents, pedestrians, cyclists, utilities, storm-water and vehicles that comprise street environments. Our focus at Urban Design Associates (UDA) has always been to re-imagine streets as the center of urban life, providing function and livability. We have seen that great streets drive the success of urban revitalization and regeneration.

The first major effort to truly separate cars and pedestrians was within Radburn, NJ, a 1929 planning experiment in a superblock development that changed the paradigm of urban design and planning. The Radburn model was a reaction to the negative safety and technical impacts of automobile culture on our cities and towns. This effort, and others like it, had the unintended effect of privileging automobile traffic over pedestrian movement and gave large parts of our urban space over to the rule of cars. Thus, we forgot to think about streets as an integral part of comprehensive public space design. The quality of our cities has suffered for it.

We should create high-quality streets because, as central aspects of our culture, they connect us to one another on many levels. American city streets occupy between 25-35% of urban developed land. We cannot let this extraordinary amount of space fall victim to the same lack of imagination and uniformity of experience that produced repetitious and uninspired suburban streets.

Fortunately, much has been written about streets and public space lately, including The Boulevard Book by Jacobs, MacDonald, and Rofe; The Language of Towns & Cities: A Visual Dictionary by Dhiru Thadani, and Street Design: The Secret to Great Cities and Towns by Victor Dover and John Massengale. These inspired works remind us of what we have forgotten. Urban designers have worked with this issue of streets to great success, balancing modes of pedestrian, cyclist and vehicle transportation to create beautiful, functional and highly livable cities. These are well-documented stories of the catalytic power of urban revitalization through the use of infrastructure and public space.

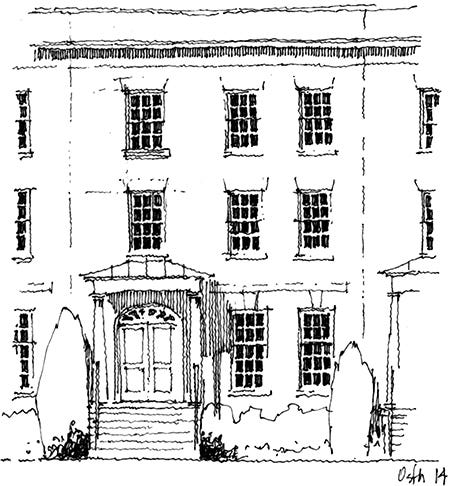

At one time, Norfolk, VA, like so many other cities, was a place that had forgotten the value of streets. The story of its revitalization reveals the opportunities streets provide. College Place in particular, embodies the important lessons of comprehensive street design and capitalizes on its ability to revitalize and enhance urban life. I spent an afternoon sketching along College Place, giving me the opportunity to rediscover the street and consider its relationship to the adjacent neighborhoods. I recorded details that I might have otherwise overlooked and experienced the day in the life of a great urban street.

UDA in Norfolk

In 1989, downtown Norfolk was a city ripe for revitalization. UDA and my partner, Ray Gindroz, FAIA, began working with the mayor, the Redevelopment Authority, and City Planning leadership in a remarkable effort to rebuild a downtown core and its contributing urban neighborhoods. We reconsidered the character and function of streets and public spaces in order to create vibrant, resilient and highly desirable urban places.

The work was extraordinary in that it changed policy, broke down institutional silos of the city government, and thus brought departments together with a core vision for revitalization. Norfolk has been fortunate in its political and administrative leadership. Through the terms of three mayors and city managers, the process continues to this day. Design of public space, something that had been lost, became the primary focus of discussion. This was a crucial move at a critical time for Norfolk.

The Downtown Norfolk 2000 Update to the city’s Master Plan included several initiatives to revive and reconnect city neighborhoods to downtown. The Freemason Neighborhood arose as a critical effort to provide high-quality urban housing immediately adjacent to and connected with downtown. The area was a mix of historic housing and industrial properties serving Norfolk’s working waterfront. In the 1960s, it was cut off from downtown when Boush and Duke Streets were converted into high-speed one-way roads designed to quickly move cars in and out of Norfolk. Between the roads, parking lots were constructed to make way for a freeway that was never built.

The Freemason planning process was an exercise in healing the downtown. This single effort balanced the quality of urban life and the downtown experience with the needs of commuters. Boush St. was restored to a mixed-use boulevard and Duke St. became a neighborhood street, connecting pedestrians and cyclists to downtown once again. In 2012, the American Planning Association named the Freemason Neighborhood one of the ten best neighborhoods in the United States.

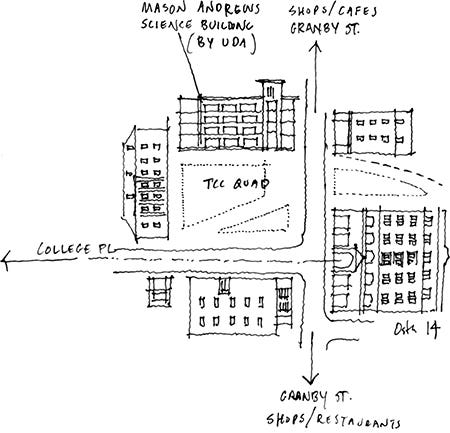

A second key initiative of the Downtown Update was to create a 3,000-student downtown campus for Tidewater Community College (TCC), adjacent to the Freemason Neighborhood. The area, originally a forgotten corner, now makes use of existing buildings and new construction around a center quad that serves as an open space for the campus.

UDA provided architectural design for the renovation of TCC’s library and a new Mason Andrews Science Building. These projects, as well as the newly established residential and student populations in the area, contributed to the successful revitalization of Granby St., Norfolk’s ‘Main Street’ of shops, cafes and restaurants that runs through the campus itself.

In all of its Norfolk efforts, UDA works with city leadership and stakeholders to develop a collaborative vision for the design and to build public and private support. The Freemason and TCC initiatives were prototypes, followed by continuous incremental revitalization to transform the city into a vibrant, walkable urban center.

A Walk on College Place

The revitalization of Norfolk is one of UDA’s proudest achievements in our 50 years in practice. As a relative newcomer to practice in Norfolk, I have the opportunity to observe the city today, without any preconceived notions of what might have been and any knowledge of the years of collaborative effort and investment to reach implementation. In particular, I was delighted to discover College Place, a street that joins the Freemason Neighborhood and TCC. It is representative of a street that has healed and embodies our goals of urban life with a variety of experience.

Although the planning in this area has been aggressive in its call for rebirth, College Place has always had energy. There were developers bold enough to build for “urban pioneers,” people with an appetite for water views and interested in city life. These new residents, and these two Master Plan Update Initiatives created the catalytic energy that shaped College Place as the heart of a neighborhood with emotional, social and financial value to the city.

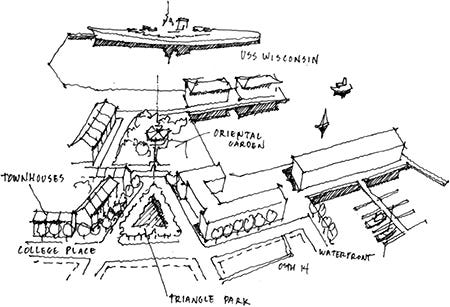

The street harmoniously incorporates a waterfront, townhouses, apartments, condominiums, offices, shops, institutional buildings and parks. It is a street that is not a prototypical “American” street, but at the same time, it is very Norfolk. Amazingly, all of this can be seen in just a few short blocks – a perfect place to spend an afternoon with a sketchbook.

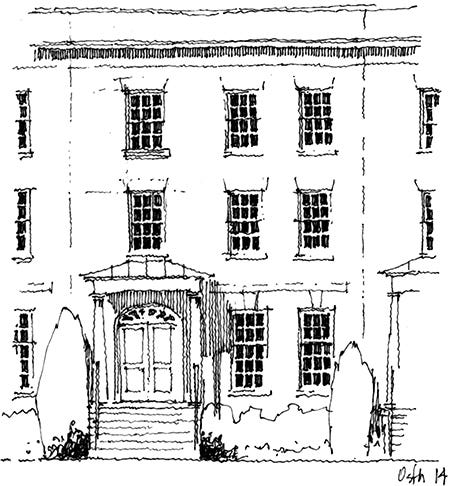

Like so many cities with a beautiful shoreline, the waterfront at the end of College Place was the first area of development. It is an intimate cove set within Norfolk’s busy working city waterfronts, home to boats of all shapes and sizes. The architecture here, from the 1970s and ’80s, shows the typical shyness for a robust expression of outdoor porch, balcony and terrace elements, that are now standard in modern city and neighborhood design.

Only one block inland is Triangle Park, an energetic green space that is lively and well used. The park’s dynamic shape creates outstanding views from within. The activity of this park is in sharp contrast to the two adjacent Norfolk landmarks to the south. Beyond a portal, is the quiet and serene Pagoda & Oriental Garden. Looming beyond the Oriental Garden is the World War II-era battleship, the USS Wisconsin, a once-ominous weapon of war, reminding us of Norfolk’s history on the world stage.

One block east of Triangle Park is a small “parklet” in the middle of College Place, an island that is as much a gateway as it is a traffic-calming device. It provides a symbolic transition from the residential neighborhood to the mixed-uses of downtown. Standing here, you can see it all: to the west, the edge of Triangle Park; to the east, busy Boush St. and TCC.

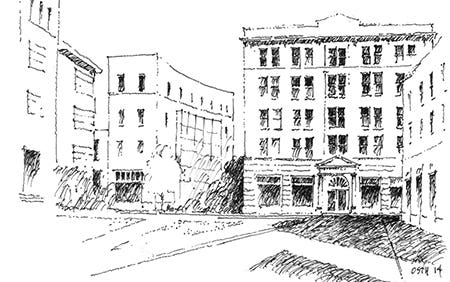

Walking east takes us to Tidewater Community College, an urban college campus at the intersection with Granby St., the ‘Main Street’ of downtown Norfolk, a street of retail, restaurants, coffee shops and music venues that activate it at all hours. College Place terminates at a former department store that now serves as a library and has become the heart of the campus.

The college quad is a harmonious public space composed of historic buildings and complementary new construction. Of the new buildings, the most prominent is the Mason Andrews Science Building designed by UDA. In the tradition of great public spaces, the building’s circulation faces the quad, stimulating it with visible activity.

As an architect and urban designer, I found that learning about College Place was a truly enjoyable experience. Drawing it took my understanding to a deeper level – the intricacies of how it works, its truly powerful shapes, and the diverse architecture. College Place hosts a collection of uses and spaces that includes pedestrians, bicycles, cars and public transit. It addresses the need for great streets as models for livable cities, and to correct long-standing urban design ills.

More and more, cities need streets that create beautiful experiences and handle various competing interests in a comprehensive manner, without privileging one over the other. These cities will work for today’s lifestyle of healthy urban living – connecting work, learning and play. Streets must be walkable, and they must create small, intimate urban spaces, transforming cities as a whole into more livable entities.

Perhaps by living and working on streets like College Place, we can remember our best, most aesthetically pleasing and useful city spaces. By re-envisioning College Place, making it part of Norfolk’s revitalization, and presenting it as a model for revitalizing cities, we can add more emotional depth and significance to urban living. Maybe we can reverse the permanence of forgetting how urban life can be valued.

Eric Osth, AIA, is a Managing Principal at Urban Design Associates in Pittsburgh, PA. Like cities and their design of public space, he had once forgotten his love of drawing. He now carries pen and paper with him at all times.