Features

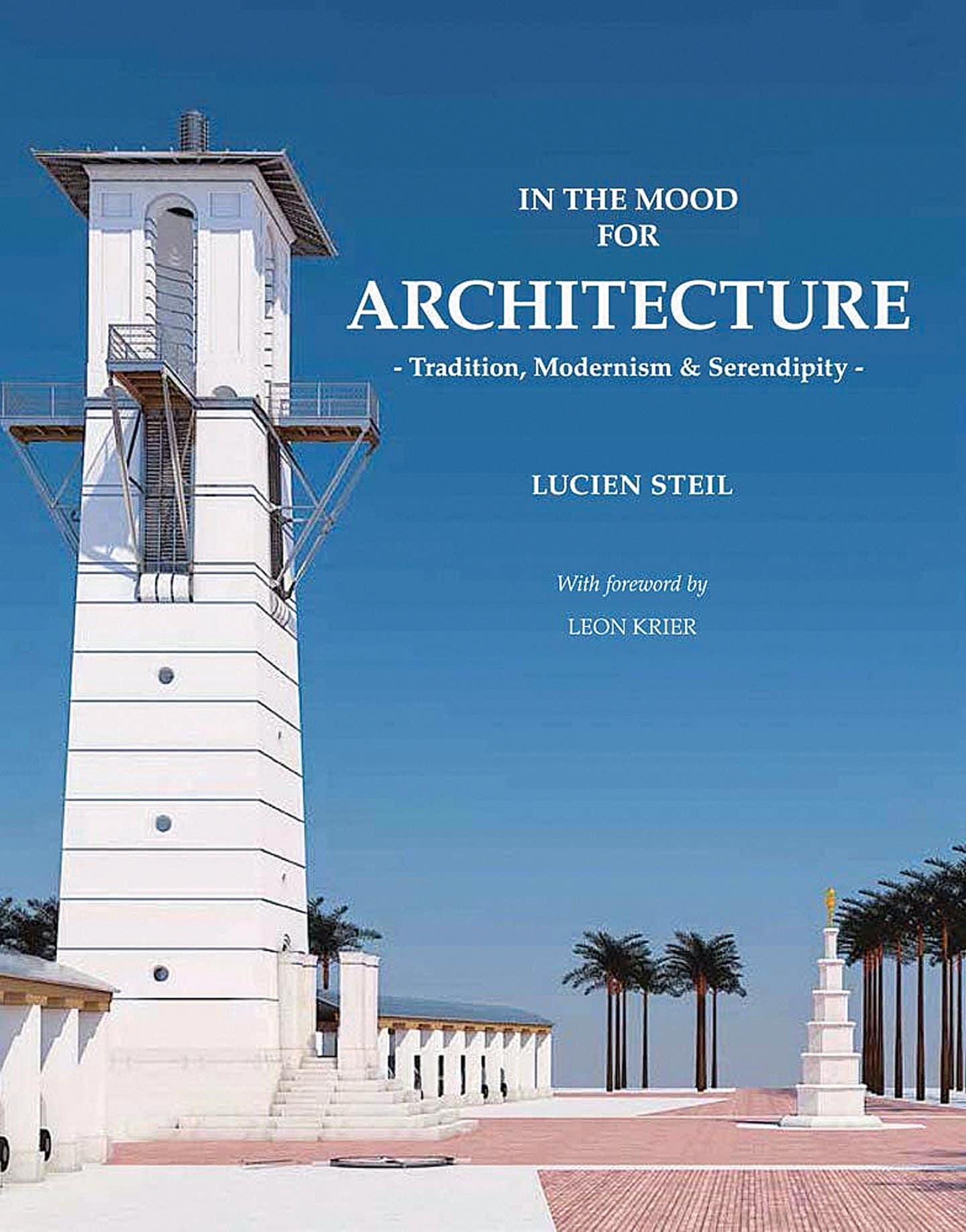

Book Review: In the Mood for Architecture—Tradition, Modernism and Serendipity

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

In the Mood for Architecture—Tradition, Modernism and Serendipity

by Lucien Steil

Wasmuth

First Edition

Hardcover

$60

In the Mood? Serendipity? What could the author possibly mean by that? It’s certainly intriguing, at least I found it so when I’d received a copy of this book in the mail as a gift from the author. That evening and three pages in, I knew I was set for a treat. How to describe? Skilfully woven throughout is what I’ve referred to as the third rail of philosophy (at least in architectural academia): Ethics. Specifically, the branches of aesthetics: judgements of how things we build ought to appeal to the senses, and morals: how the things we design affect the people who construct them as well as those expected to live, work, or otherwise interact with them. However, this subject is not treated in a dry, esoteric manner, rather conveyed in a very down-to-earth manner with repeated appeals to common sense and human decency.

Memory and Forgetfulness

Much of the aforementioned consideration of ethics is reflected in a discussion of traditional architecture juxtaposed with Modernism. Tradition carries the sense of something that is passed across the threshold from one generation to the next. However, not everything makes it. Tradition in architecture “sifts out” the most durable, the most beautiful, the most conducive to civic life. In so doing, the author describes it as a project of perpetual becoming. By retaining the best solutions of previous generations and adding contemporary contributions, it sits as the nexus of permanence and change. Whereas tradition could be said to be the collective memory of a culture, traditional architecture acts as a material re-enactment and extension of that shared memory.

“There can be a culture of forgetting only, and these periods are called Dark Ages.”

Modernism as an ideology posits itself as antitraditional. Materially, it has aligned itself with Industrialisation. Metaphysically, it manifests a longing for Utopia, literally a “no place” fixated on an ever-receding future, what the author describes as an endless beginning. He further surmises that this overinvestment in and fixation upon the future betrays a fear of the “present’s own potential for a better world,” one that diverts all attention from the local here and contemporary now. Modernism has pressed its adherents and much of society at large into forgetfulness; to forget that “the essential purpose of all these built works has not been to reflect on contemporaneity” but “to provide a meaningful setting for life.”

Originality and Imitation

Genius has been alternatively called a divine gift or in more recent times thought of as an inherent aptitude. Holding this perspective, genius is not something that can be taught. Nevertheless, in schools of architecture it seems to be the default expectation. As such, technique and expertise are no longer viewed as creative activities and as a result the means to teach and train all of the lessons embedded in tradition have been largely lost. As it turns out tradition is not something one can inherit genetically, you have to work very hard for it.

This is where the concept of originality may serve as a corrective. As the name implies, true originality means a return to discovery of the original creation, the metaphorical bringing of order out of chaos. The traditional means for doing so have lay in imitation which can be thought of in at least three different ways. Initially, a copy is “concerned with the mechanical and literal replication of originals.” Rather than something to be derided, this technique driven activity sharpens skill and serves as a firm foundation for creative activity. Whereas a copy is concerned with reproducing a pastiche seeks of convey an impression of the original. Of course, there could true or false, good or bad impressions. A pastiche might be better thought of as a means of expression rather than a term of contempt. Finally, there is imitation, which amounts to the reconstitution of the original. Traditionally, nature has been the source of origin for architectural inspiration as expressed by Sir Geoffrey Scott, “This order which in Nature is hidden and implicit, Architecture makes patent to the eye.” Imitation is therefore the maturation of artistic and intellectual intentions concerned with expressing the very essence of things.

There is much more to In the Mood for Architecture than what I’ve previously highlighted. There is a detailed critique of starchitecture and skyscrapers as well as a thoughtful consideration of the civic role of towers and monuments. Quite encouraging, there is an extensive review of case studies of contemporary architecture that apply the traditional principles and lessons outlined at the outset of the book. What shines throughout is the author’s passion for architecture as a place of dwelling for you and I. Lucien Steil is clearly an advocate for the types of buildings, communities, and landscapes that everyday people love and feel completely at home with.

My name is Patrick Webb, I’m a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of natural, historically utilized plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime in contemporary architectural specification.

I was raised by a father in an Arts & Crafts tradition. Patrick Sr. learned the “decorative” arts of painting, plastering and wall covering as a young man in England. Raising me equated to teaching through working. All of life’s important lessons were considered ones that could be learned from the mediums of tradition and craft. I found myself most drawn to plastering as I considered it the richest of the three aforementioned trades for artistic expression.

This strong paternal influence was tempered by my grandmother, Geraldine Webb, a cultured, traveled, well-educated woman, fluent in several languages. She made a point of instructing her young grandson in Spanish, French, formal etiquette and opened up an entire worldview of history and culture.

After three years attending the University of Texas’ civil engineering program with a focus on mineral compositions, I departed, taking a vow of poverty, living as a religious aesthetic for a period of seven years. This time was devoted to clear reasoning, linguistic studies, examination of world religions, exploration of ethics and aesthetics. It acted as a circuitous path leading back to traditional craft, now imbued with a deeper understanding of interconnection in time and place. I ceased to see craft as simply work or labor for daily bread but among the sacred outward expressions of the divine anifest

within us.

From that time going forward there have been numerous interesting experiences. Among them study of plastering traditions under true masters here in the US as well as in England, Germany, France, Italy and Morocco. Projects have included such high expressions of plasterwork as mouldings, ornament, buon fresco, stuc pierre, sgraffito and tadelakt.

I’ve been privileged to teach for the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, where I currently reside and for the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art across the US. “Sharing is caring” – such a corny cliché but so true. I hardly know a

thing that hasn’t been practically served to me on a platter. I’m grateful first of all, but now that I might actually know a few things, it becomes my responsibility to be generous as well.